As US cases soar, ‘coronavirus detectives’ face new pressure

Loading...

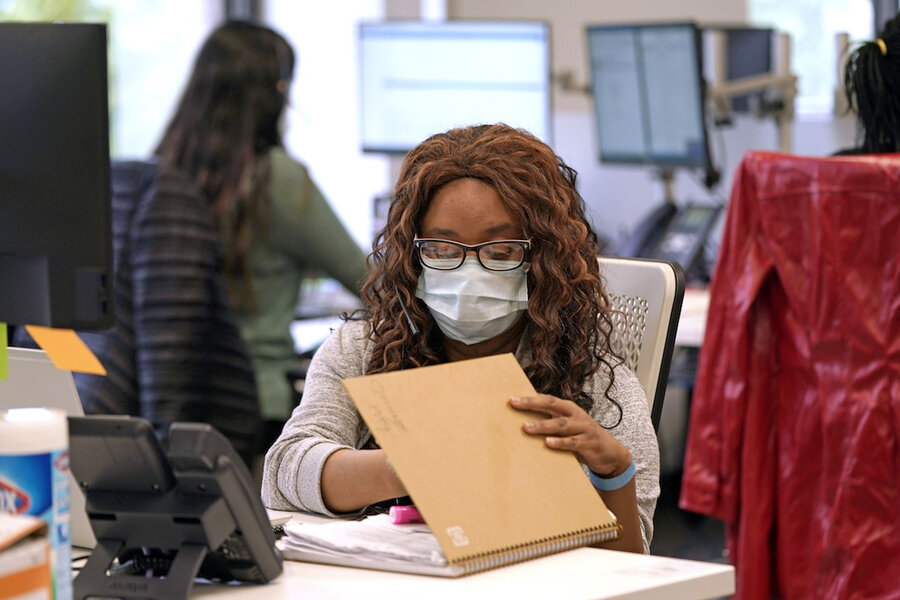

Since the novel coronavirus began to spread in the United States in February, health departments across the country have recruited and trained armies of contact tracers, workers who locate and speak with people who have been exposed to the virus.

Contact tracing is a tried-and-tested method for quashing outbreaks, but, as cases surge across the South and West, the capacity is buckling, sending a stark warning to other states that were bracing for a fall wave of infections.

Why We Wrote This

Curbing a pandemic requires an army of public health workers who can find, contact, and support those thought to have been exposed to the disease. Some states aren’t prepared.

In Florida, the state health department has about 1,600 contact tracers, and has contracted a company to provide 600 more. But by one estimation, the state ought to have 33,000 contact tracers. Texas has around 2,800 contract tracers, well below the goal of 4,000 that the state’s governor set in April as a metric for reopening.

“Contact tracing for COVID is primarily going to work well before you get into a huge spike of cases. Right now, with the daily case count [in Florida] it’s unlikely that any health department is going to keep up,” says Marissa Levine, a former state health commissioner in Virginia.

When a novel coronavirus first began to spread in February, U.S. public health officials reached for a tried-and-tested method: contact tracing. By isolating potential spreaders and finding out who else they may have infected, “coronavirus detectives” try to tamp down outbreaks.

In hard-hit cities like New York and Boston, contact tracers were quickly overwhelmed by the growth in cases, and politicians turned instead to lockdowns to slow transmission and lessen the pressure on hospitals.

Since then, health departments across the country have built up their tracing capacity, training a corps of workers, including students and volunteers, in how to contact people who have been exposed to the virus, and to monitor and support those who isolate themselves.

Why We Wrote This

Curbing a pandemic requires an army of public health workers who can find, contact, and support those thought to have been exposed to the disease. Some states aren’t prepared.

But as cases surge across the South and West, this capacity is buckling, sending a stark warning to other states that were bracing for a fall wave of COVID-19 infections. Far from quashing outbreaks, tracers in states like Texas and Arizona are playing catch-up, stymied by social norms, political discord, and the dizzying rate of post-lockdown infections. Even California, which has trained thousands of new contact tracers since May, has been caught flat-footed.

Editor’s note: As a public service, all our coronavirus coverage is free. No paywall.

Perhaps nowhere is this tension more acute than in Florida, where a surge in positive cases is blamed on young revelers flocking to bars and beaches and partying with friends and strangers.

“Contact tracing for COVID is primarily going to work well before you get into a huge spike of cases. Right now, with the daily case count [in Florida] it’s unlikely that any health department is going to keep up,” says Marissa Levine, a former state health commissioner in Virginia.

Florida’s state health department has about 1,600 people working on contact tracing and has contracted a company to provide 600 more. In a state of 21 million people, that’s roughly two-thirds of a recommended baseline of 15 tracers per 100,000 people. But when adjusted for Florida’s COVID-19 case count, that ratio rises to 156 per 100,000, or more than 33,000 tracers, according to an online contact tracing workforce estimator at George Washington University.

Texas has around 2,800 contract tracers, compared with a goal of 4,000 that Gov. Greg Abbott set in April as a metric for reopening. That workforce has declined in recent weeks as state workers were deployed to other COVID-19 response jobs, The Texas Tribune reported.

“Not about surveillance”

Ideally, contact tracers will both locate people exposed to an infectious disease and plot the chain of infection back to the source, says Dr. Levine, who directs the Center for Leadership in Public Health Practice at the University of South Florida. “The whole idea is to identify places where people have been congregating and it has been spreading.”

Nationally, the U.S. now has between 27,000 and 28,000 contact tracers, Robert Redfield, the director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, said last month. Some experts have concluded that at least 100,000 tracers are required, and pointed to the success of countries like South Korea and Germany in deploying rapid testing and tracing to contain COVID-19.

In April, Congress allocated $631 million for contact tracing, testing, and surveillance efforts at local health departments, which some have used to train staff or volunteers who can then be called up when cases spike. Others have tapped state workers idled during lockdowns.

But secondments aren’t a substitute for a standing army, says Mike Reid, an assistant professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco who has trained more than 4,000 tracers for California’s health departments. In San Francisco “many of our contact tracers are librarians and city attorneys and environmental scientists. Some of them are feeling the pressure to go back to their day jobs,” he says.

For now, San Francisco has told city workers to keep working on contact tracing amid a surge in positive cases in Los Angeles following the lifting of a statewide lockdown in May. Gov. Gavin Newsom said Monday that young adults who believed themselves “invincible” were catching and spreading the virus.

The Bay Area’s caseload has risen more slowly, and tracers are reaching most of those who test positive, but Dr. Reid is watching other hot spots warily. “If the numbers continue to grow we’re going to have to continue to train more people [to contact trace], and that will require greater investment,” he says.

Nearly half of the tracers hired for the Bay Area are Spanish speakers, a reflection of its demographics and of the disease’s unequal toll on minorities. Contact tracers must navigate cultural and linguistic barriers, and build a rapport with people who equate tracing with immigration enforcement and for whom self-isolation could be a crushing burden.

One way to do that, says Joia Mukherjee, the chief medical officer at Partners in Health, a global health nonprofit in Boston, is to ensure you can properly support those whom you ask to isolate, such as finding temporary housing or supplying baby formula. “Contact tracing is about care. It’s not about surveillance,” she says.

A marathon, not a sprint

In Massachusetts, Partners in Health has worked with Gov. Charlie Baker who committed $44 million to build a central COVID-19 tracing force to supplement local health departments. After hitting a peak of 1,900 people, this force has fallen to 400 as the state’s caseload has declined to fewer than 200 a day, but it can scale up again quickly when needed, says Dr. Mukherjee.

Partners in Health is supporting contact tracing at health departments in several other states, including in at-risk communities of color, including agricultural workers in Immokalee, Florida.

Dr. Mukherjee, who has worked for decades on infectious diseases in developing countries, says social trust is always a challenge. What is “uniquely American” in tackling the pandemic “is the erosion of a belief in science and an erosion of trust in government.”

In Palm Beach, contact tracers are only reaching 72% of people who tested positive. (Massachusetts has averaged 90%.) Of their close contacts whose details were shared, tracers were able to contact about half, the county health director said last month, adding that many of the people who were infected had refused to tell tracers where they worked.

As the virus surges in Sun Belt cities, others are only now starting to ramp up contact tracing. In Illinois, Cook County last week unveiled a $41 million initiative for Chicago’s suburbs that would expand its tracing team from 25 to 400 staff, working with universities and community-based organizations. The first cohort is expected to start work in early August, said a spokeswoman for the county department of public health.

That timeline may seem leisurely, as states reopen and COVID-19 hot spots flare across the South and West. Epidemiologists say building tracing capacity and getting the message out to at-risk communities is simpler and more effective during lockdowns than after, when social interactions multiply.

Still, Dr. Mukherjee says it’s never too late to start. Pandemics are marathons not sprints, and when tracers and health systems are put in place, “we can jump on outbreaks much more rapidly,” she says.

Editor’s note: As a public service, all our coronavirus coverage is free. No paywall.