Did life on Earth come from space? Chummy microbes offer clues.

Loading...

Where did life on Earth come from? Scientists know that about 4.4 billion years ago, microorganisms appeared on the planet and began to evolve. But they don’t know how a lifeless Mother Earth produced them in the first place.

One possible explanation is that she didn’t. Instead, the idea goes, microbes arrived from elsewhere in space. This hypothesis, known as panspermia, remains little supported, but an experiment aboard the International Space Station shows how microbes could have survived travel between Mars and Earth.

Why We Wrote This

The origin of life on Earth is perhaps biology’s biggest mystery. But what if life originated somewhere else?

A study published Wednesday describes how scientists placed aggregates of dried bacteria on exposure panels outside the space station. After three years, in the vacuum of space, some of the single-celled organisms survived. Cells on the outside layer died, but protected those within.

“We are what we are, but it should perhaps let us realize better that we are part of the universe,” says Purdue University geophysicist Jay Melosh, a proponent of the panspermia hypothesis. “We’re not just confined to our own little planet. We’re the offspring of a truly interplanetary process.”

Where did life on Earth come from? Scientists know that sometime around 4.4 billion years ago, microorganisms appeared on the planet and began to evolve. But they don’t know how a lifeless Mother Earth produced them in the first place.

One possible explanation is that she didn’t. Instead, the idea goes, microscopic lifeforms fell to Earth from space, after traversing the harsh vacuum from another planet.

Many researchers consider this hypothesis, called panspermia, unlikely. But a study published Wednesday shows how single-celled organisms might have survived a journey from, say, Mars to the early Earth through space.

Why We Wrote This

The origin of life on Earth is perhaps biology’s biggest mystery. But what if life originated somewhere else?

Questions remain about the numerous challenges microbes would face along the way. But if panspermia is indeed possible, and life can be readily dispersed throughout the cosmos, it would fundamentally change how we earthlings see ourselves.

“We are what we are, but it should perhaps let us realize better that we are part of the universe,” says Jay Melosh, distinguished professor of earth and atmospheric science at Purdue University in West Lafayette, Indiana. “We’re not just confined to our own little planet. We’re the offspring of a truly interplanetary process.”

Seeds of life

Most scientists say that Earth-life probably did originate on Earth. The standard thinking goes that somehow the conditions were ideal for just the right minerals to come together in a series of chemical reactions that yielded self-replicating molecules, that is, early life. But the particulars of that scenario have been tricky to pin down, leaving room for other possibilities.

The concept of panspermia was kicked off, in part, by the humongous eruption of a volcano on the island of Krakatoa in 1883, says Dr. Melosh. The eruption completely sterilized the island, but just months later, life began to flourish anew. Naturalists explained that the miraculous regeneration came from seeds and insects floating on the winds or the tides from nearby islands, and that got some scientists thinking about the cosmos. Perhaps early Earth was like a barren island, too, they speculated, and the seeds of life or life itself drifted around space and alighted on our planet at just the right moment.

Since then, scientists have learned that the bombardment of cosmic radiation makes it extremely difficult for any kind of life as we know it to survive a journey through space. But for some scientists, the panspermia hypothesis still holds promise.

Dr. Melosh is one of those scientists, and some four decades ago, he proposed that, rather than drifting naked through space, microorganisms might survive that harsh environment in a protected place within rocks. According to this conjecture, life may have been present inside rocks on, say, Mars. And when an impact on the red planet ejected some of those rocks into space, one eventually wound up landing on Earth. Indeed, of 60,000 or so meteorites discovered on Earth so far, nearly 300 are thought to have originated on Mars.

Other researchers have focused instead on whether there are organisms that could survive the harshness of space. To do that, one team of researchers in Japan decided to send some bacteria into space for a few years.

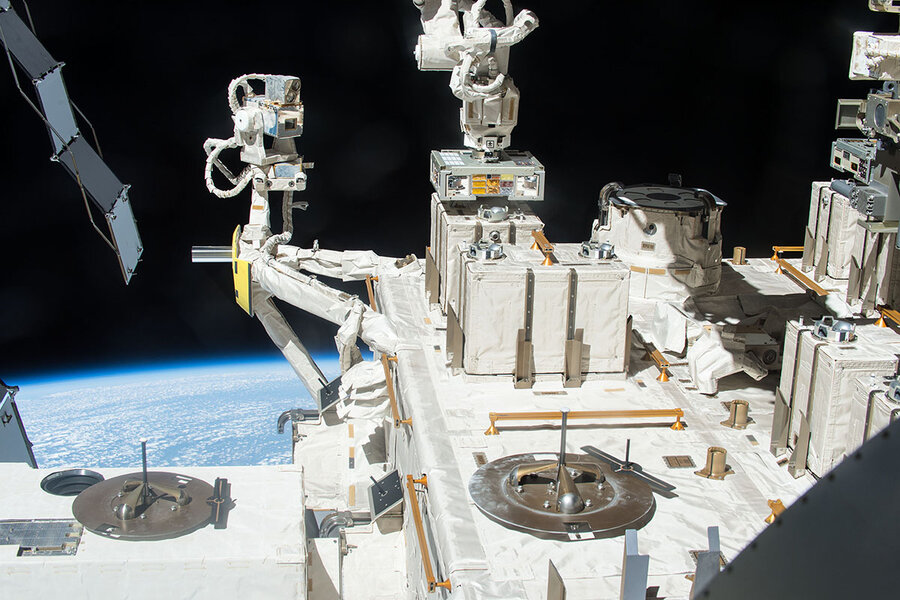

They focused on one particular group of bacteria known to be resistant to radiation and quite resilient: Deinococcus. The team took dried-up colonies of that bacteria and placed them on exposure panels outside the International Space Station. The samples were exposed to the space environment for one, two, and three years.

As it turns out, after three years, some of the bacteria had survived. In fact, although the outside layer of the colony did perish, it ended up creating a protective layer for the microbes underneath. The team’s results are reported in a paper published in the journal Frontiers in Microbiology on Wednesday.

“Our life might [have] originated in Mars if panspermia is possible,” says Akihiko Yamagishi, an astrobiologist at the Tokyo University of Pharmacy and Life Sciences and the lead author of the new study.

It’s not just about radiation, though. Life as we know it requires water. So how long could a living organism survive being dried out? Previous research has found that spores of a common bacteria, Bacillus subtilis, can survive in space.

But for how long? A rock that’s been broken off of another planet and flung into space probably doesn’t take a direct path to Earth. Rather, it likely falls into an orbit around the sun and is slowly pulled into different trajectories by the gravity of larger space rocks over time. Eventually it may cross paths with the Earth, but that could take millions of years – or longer.

And even if life did survive the trip through space, and then through Earth’s thick atmosphere, it might not be so happy on the surface of the planet, says Steven Benner, a chemist at the Foundation for Applied Molecular Evolution in Alachua, Florida. These organisms would be adapted for the environment of another planet, and then for survival in space, so Earth might seem like a particularly hostile environment, he says.

“You know, they’re not used to going to Wawa or 7-Eleven for groceries; they’re used to going to the Martian equivalent,” says Dr. Benner. “And maybe the Martian equivalent has food that’s much different than what they’re going to be having access to on Earth.”

Are we all Martians?

Mars today does not seem very inviting for life, but billions of years ago, the red planet was much more like Earth is today, with flowing rivers, lakes, and oceans. One big question that remains is whether life has ever existed on Mars.

NASA’s latest mission to Mars launched last month, and it aims to sniff out a definitive answer to that question. The new rover, named Perseverance, is equipped to search for signs of past life on Mars and to bag rock samples to be returned to Earth for further study on a future mission.

Although he famously entertained the panspermia model for the origin of life on Earth at a conference a decade ago, today Dr. Benner is dubious. At the time, he says, geologists thought that Earth 4.4 billion years ago was a water world with no dry land to speak of and scientists thought some dry land would be needed for life to arise. But since then, that view has changed and geologists have said dry land might have been around at the right time.

“So we don’t really need Mars,” Dr. Benner says. “Certainly life emerging on Earth does not seem to be such a wild improbability that we require places elsewhere.”

Dr. Melosh is still keen on the idea, however, as the surface of Mars likely did have just the right conditions at the time. Still, he says, “It’s a more complicated solution. And it really doesn’t solve the problem of the origin of life. It just puts it back a [bit]. ... Maybe you buy a few hundred million years that way.”