Can scientists predict dangerous solar flares? New research shows promise.

Loading...

New research on the bursts of radiation that flare off the sun and sometimes disrupt life on Earth is helping scientists better understand the physics behind these solar weather events. By understanding what causes these solar flares, scientists someday will be able to predict them and thus give Earthlings more time to prepare.

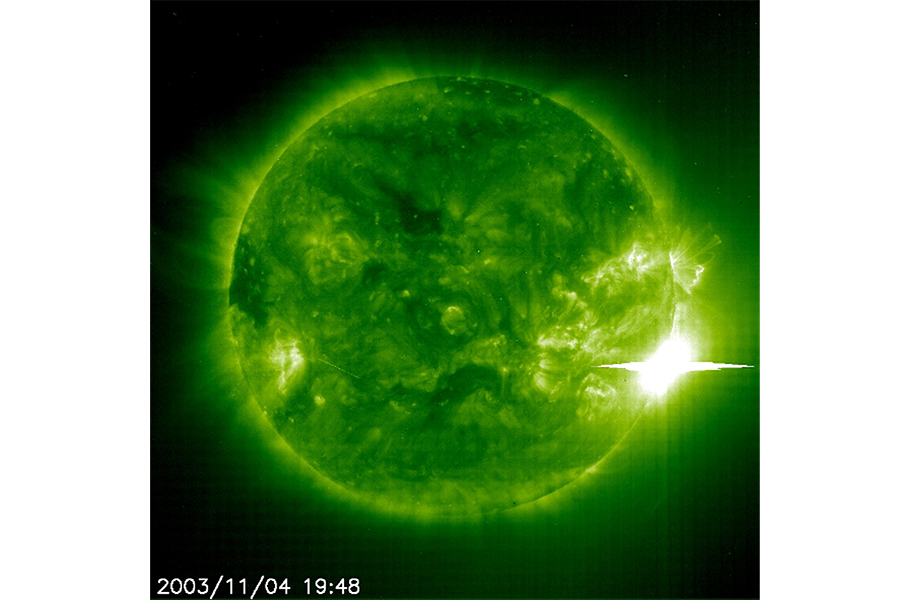

Solar flares, which can happen as frequently as a few times a day, are explosions of radiation that come from the release of energy stored in the sun’s magnetic field. When this barrage of radiation reaches the Earth – without warning, because it moves at the speed of light – it can damage sensitive electronics on satellites and interfere with their transmissions by exciting the Earth's upper atmosphere.

“We really have to advance our capabilities to predict those [solar flares] in the future,” says Michael Kirk, a NASA solar physicist, in an interview with The Christian Science Monitor. “As a society we don't think about this most of the time – and that’s OK – but it can really affect our lives,” he says.

In paper published April 19 in The Astrophysical Journal Letters, astrophysicists from the US and China report that, by studying images of a December 2013 solar flare collected by three solar observatories, they have found significant evidence that a predicted electromagnetic phenomenon called a “current sheet,” a sliver of electrically charged material at the surface of the sun, actually exists. If true, this helps support current theories about the forces behind solar flares.

“The existence of a current sheet is crucial in all our models of solar flares,” said James McAteer, an astrophysicist at New Mexico State University and an author of the study, said in an announcement. “So these observations make us much more comfortable that our models are good,” he said.

As NASA describes:

Current sheets are formed in the space between two oppositely aligned magnetic fields that are in close contact. These oppositely aligned fields can explosively realign to a new configuration, in a process called magnetic reconnection. Because current sheets are so closely tied to magnetic reconnection, observations of a current sheet during a December 2013 solar flare bolster the idea that solar flares are the result of magnetic reconnection on the sun.

Though solar flares are not unusual, and this isn’t the first time scientists have observed a current sheet during a solar flare, this study provides the most comprehensive measurement of the physical characteristics of a current sheet – such as speed, temperature, density and size, says NASA.

The authors of Tuesday’s paper analyzed images collected from NASA’s Solar Dynamics Observatory, the agency’s Solar and Terrestrial Relations Observatory, and the Hinode observatory, which is run in partnership with the Japanese and European space agencies.

“You have to be watching at the right time, at the right angle, with the right instruments to see a current sheet,” said Dr. McAteer. “It’s hard to get all those ducks in a row,” he said.

Solar flares are often accompanied by the ejection of electrically charged plasma from the sun's corona. This stream of plasma, known as a coronal mass ejection, can disrupt satellites in orbit and occasionally blows out transformers on power grids, too.

Unlike solar flares, coronal mass ejections travel much slower than speed of light, so scientists can detect them 12 to 26 hours ahead of time and warn satellite operators to put their space-equipment in safe mode, or to turn satellites away from the sun.

The frequency of solar flares rises and falls on an 11-year cycle. In the low part of the cycle, solar flares only happen once every few days, but in the peak period, they occur several times a day. The most recent "solar maximum" came in 2014.

One major impact of these radiation bursts, besides damage to satellites, is that they interfere with radio frequencies, which can cause airlines to lose radio communication when they travel over the Earth’s poles. When solar weather can be predicted, says Kirk, airlines can prepare by rerouting their planes over latitudes away from the poles.

“We’re very vulnerable to space weather,” says Kirk.