Japanese attempt to unleash 2,300-foot whip on 'space junk' fails

An experimental tactic to clean up “space junk” failed to get the job done, Japanese officials said Monday, marking a disappointing foray into efforts to trap and destroy tens of millions of pieces of debris circling the Earth.

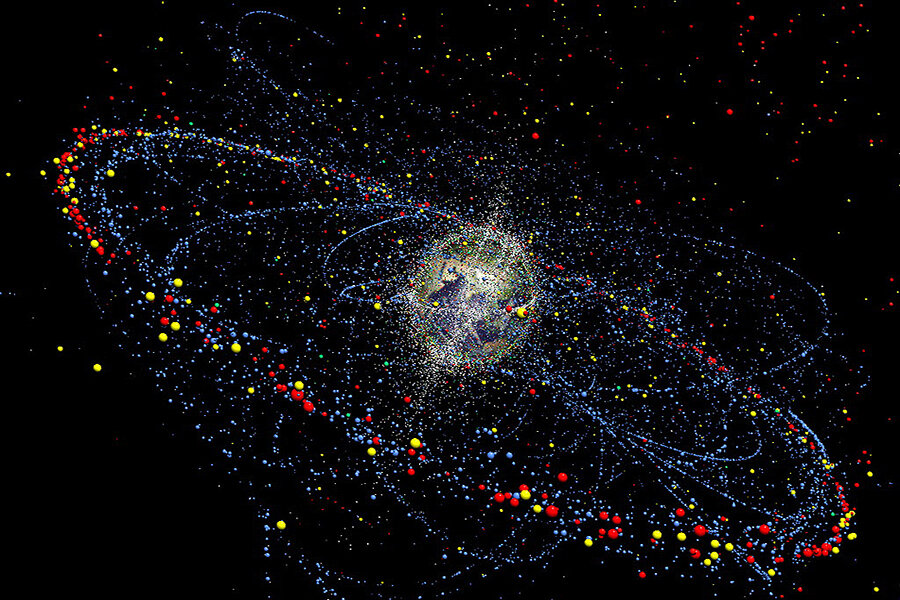

Space junk, which consists predominantly of debris from satellites and rockets that has broken off during collisions and started orbiting the Earth, has become a growing problem for astronauts (see the 2013 movie, "Gravity.) While researchers estimate that more than 100 million pieces of the rubbish orbit the Earth, they don’t know the full extent of the issue – in part because the vast majority are smaller than a baseball, making the fragments difficult to detect and track down.

And those small pieces are likely more damaging than they would appear. The fragments can travel at speeds of up to 17,000 mph, allowing particles to move at velocities that could damage spacecraft, including the International Space Station (ISS) if they make contact, prompting scientists to search for new ways to try to catch and destroy the debris.

Researchers with the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency developed and began testing an electrodynamic, 700-meter-long tether-like device, which was designed to extend from the body of a cargo ship bringing supplies to astronauts at the ISS. They hoped the tether, which was made from thin wires of stainless steel and aluminium, would slow the orbiting trash down and catch it. The device would then carry the debris to a lower orbit, where it would enter the atmosphere and burn up before colliding with the Earth’s surface.

But after working for several days to release the tether, scientists gave up. On Monday, it re-entered the atmosphere aboard the vessel without capturing any space junk.

"We believe the tether did not get released," leading researcher Koichi Inoue told reporters, according to AFP. "It is certainly disappointing that we ended the mission without completing one of the main objectives."

The failure was another disappointment for Japanese space researchers, who aborted a mission intended to launch a satellite into orbit several weeks ago.

Scientists have considered other techniques to trap and destroy space junk, including using lasers to vaporize the debris or sending small satellites into space that would trap particles and combust along with them.

But none of these have ideas have proved a clear solution to the problem, and researchers worry that the issue will only escalate as the particles continues to collide with one another, breaking into smaller pieces that add to the collection of debris.

"There is a wide and strong expert consensus on the pressing need to act now to begin debris removal activities," Heiner Klinkrad, head of the European Space Agency's Space Debris Office, said in a statement at the 2013 European Conference on Space Debris, held in Germany. "Our understanding of the growing space debris problem can be compared with our understanding of the need to address Earth’s changing climate some 20 years ago."