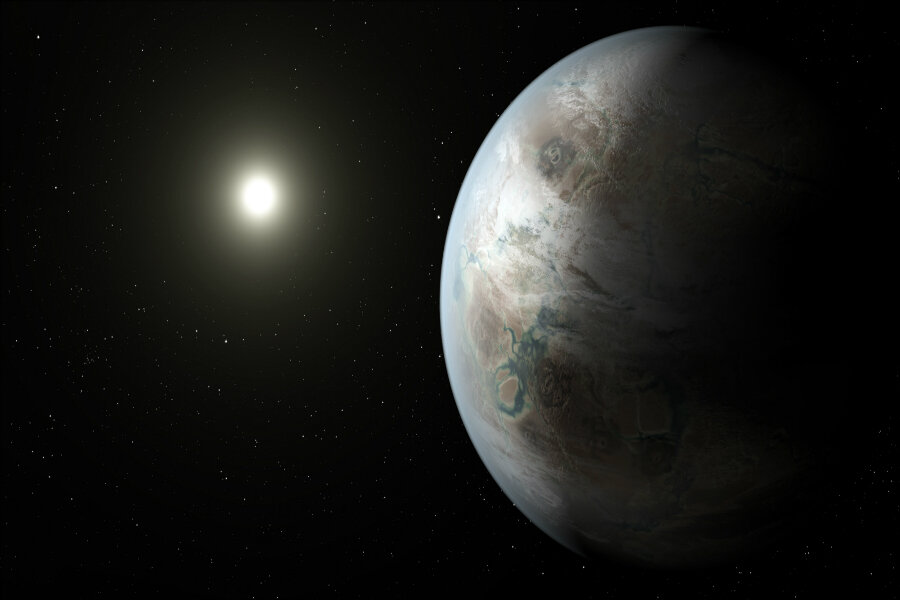

Kepler telescope discovers new batch of 'just right' planets that could foster life

| Washington

NASA's planet-hunting telescope has found 10 new planets outside our solar system that are likely the right size and temperature to potentially have life on them, broadly hinting that we are probably not alone.

After four years of searching, the Kepler telescope has detected a total of 49 planets in the Goldilocks zone. And it only looked in a tiny part of the galaxy, one quarter of one percent of a galaxy that holds about 200 billion of stars.

Seven of the 10 newfound Earth-size planets circle stars that are just like ours, not cool dwarf ones that require a planet be quite close to its star for the right temperature. That doesn't mean the planets have life, but some of the most basic requirements that life needs are there, upping the chances for life.

"Are we alone? Maybe Kepler today has told us indirectly, although we need confirmation, that we are probably not alone," Kepler scientist Mario Perez said in a Monday news conference.

Outside scientists agreed that this is a boost in the hope for life elsewhere.

"It implies that Earth-size planets in the habitable zone around sun-like stars are not rare," Harvard astronomer Avi Loeb, who was not part of the work, said in an email.

The 10 Goldilocks planets are part of 219 new candidate planets that NASA announced Monday as part of the final batch of planets discovered in the main mission since the telescope was launched in 2009. It was designed to survey part of the galaxy to see how frequent planets are and how frequent Earth-size and potentially habitable planets are. Kepler's main mission ended in 2013 after the failure of two of its four wheels that control its orientation in space.

It's too early to know how common potentially habitable planets are in the galaxy because there are lots of factors to consider including that Kepler could only see planets that move between the telescope vision and its star, said Kepler research scientist Susan Mullally of the SETI Institute in Mountain View, Calif.

It will take about a year for the Kepler team to come up with a number of habitable planet frequency, she said.

Kepler has spotted more than 4,000 planet candidates and confirmed more than half of those. A dozen of the planets that seem to be in the potentially habitable zone circle Earth-like stars, not cooler red dwarfs.

Circling sun-like stars make the planets "even more interesting and important," said Alan Boss, an astronomer at the Carnegie Institution, who wasn't part of the Kepler team.

One of those planets – KOI7711 – is the closest analog to Earth astronomers have seen in terms of size and the energy it gets from its star, which dictates temperatures.

Before Kepler was launched, astronomers had hoped that the frequency of Earth-like planets would be about one percent of the stars. The talk among scientists at a Kepler conference in California this weekend is that it is closer to 60 percent, he said.

Kepler isn't the only way astronomers have found exoplanets and even potentially habitable ones. Between Kepler and other methods, scientists have now confirmed more than 3,600 exoplanets and found about 62 potentially habitable planets.

"This number could have been very, very small," said Caltech astronomer Courtney Dressing. "I, for one, am ecstatic."