Nuclear power’s new debate: cost

Overlooking the shimmering waters of Chesapeake Bay, the massive twin concrete domes of the Calvert Cliffs nuclear power station’s two reactors could soon see a third sister rising alongside them.

If construction begins in Lusby, Md., perhaps by 2012, Calvert Cliffs III will be part of the larger promise of a “nuclear renaissance” of reactor construction sweeping the globe, proponents say.

By providing safe, domestic, moderately priced, and greenhouse-gas-free energy, nuclear power will be “a critical component of America’s future,” says George Vanderheyden, president of UniStar Nuclear Energy LLC, developer of Calvert Cliffs III.

Yet a new wave of concern is rising – not over traditional anxieties such as radioactive waste or weapons proliferation – but about the mammoth financial cost of nuclear power and who will bear it.

The big hurdle for Calvert Cliffs III and at least 21 other nuclear power reactors now in the US development pipeline is all about money – finding the billions in loans to build them. And the key to getting those loans is winning federal guarantees to back them.

Today, the US has 104 nuclear reactors, providing about 20 percent of the nation’s power. No new nuclear plants have been ordered in the US since 1978. This is not because of protestors, but because of a lack of investor funding and Wall Street remembering the ghosts of nuclear power’s past – massive construction cost overruns, utility defaults, and bankruptcies. Yet these no longer seem to haunt the nuclear industry or its supporters.

A new nuclear enthusiasm has now emerged quite powerfully in Congress.

House Republicans in June unveiled a plan for 100 new US nuclear reactors. A Senate proposal calls for a 20-year construction schedule, costing $700 billion. Industry will pay the full freight, according to the Senate plan. While there must be federal loan guarantees in order to convince Wall Street to fund the projects, in the end, the system will cost taxpayers “zero dollars,” it says.

Echoing that push, the Democrat-controlled Senate in May put its stamp on energy-climate legislation that has buried in it the potential for hundreds of billions of dollars in loan guarantees for “clean energy” – the lion’s share destined for nuclear power, critics say.

“The Senate energy committee has passed legislation that could provide unlimited loan guarantees for new nuclear reactors ,” says Michele Boyd, head of the safe-energy program for Physicians for Social Responsibility.

No nuclear plants in the US are under construction yet because they haven’t secured federal licenses or loan guarantees, many observers say. Such guarantees would become a huge stimulus for the nuclear power industry, enabling utilities to borrow billions from Wall Street or the federal finance bank.

“Despite industry efforts to frame nuclear energy as the cheapest option, the reality is that nuclear power’s very survival has required large and continuous government support,” writes Doug Koplow, president of the Boston energy consulting company Earth Track, in a recent analysis of public subsidies for nuclear power. Mr. Koplow tracks $178 billion in public subsidies for nuclear energy for the period from 1947 to 1999. Others have reached similar figures.

ALTOGETHER, NUCLEAR-INDUSTRY BAILOUTS in the 1970s and ’80s cost taxpayers and ratepayers in excess of $300 billion in 2006 dollars, according to three independent studies cited in a new nuclear-cost study by the Union of Concerned Scientists.

New guarantees in coming years could also leave US taxpayers picking up the tab if nuclear utilities defaulted on their loans. In 2008, the Government Accountability Office said the average risk of default on Department of Energy guarantees was about 50 percent. The Congressional Budget Office projected that default rates would be very high – well above 50 percent.”

On that basis, the potential risk exposure to US taxpayers from federally guaranteed nuclear loans would be $360 billion to $1.6 trillion, depending on the number of power reactors built, the Union of Concerned Scientists’ study found.

“You want to talk about bailouts – the next generation of new nuclear power would be Fannie Mae in spades,” says Mark Cooper, senior fellow at Vermont Law School’s Institute for Energy and the Environment. Dr. Cooper is among several economic analysts who contend that – waste and safety issues aside – nuclear energy is too costly.

“Funding nuclear power on anything like the scale of 100 plants over the next 20 years would involve an intolerable level of risk for taxpayers because that level of new nuclear reactors would require just massive federal loan guarantees,” says Peter Bradford, a former member of the Nuclear Regulatory Commission and former chairman of the New York State Public Service Commission.

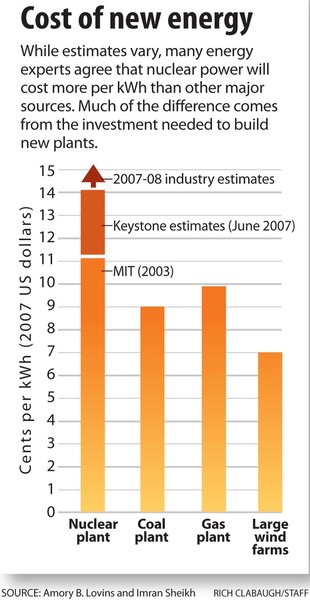

Even if no loans were defaulted on, nuclear would be too expensive, Cooper says. The multitrillion-dollar cost eclipses most energy sources, such as wind power, which also has a sizable up-front capital cost. But wind’s lifetime cost is roughly one-third less than current estimates for nuclear, Cooper’s and others studies show. So who would want to invest in such costly electricity? Not Wall Street – at least not without loan guarantees.

Even during the heady days of 2007, Wall Street’s seven biggest banks were wary. In a letter to the Department of Energy, they advised the federal government that they would require 100 percent federal loan guarantees to help finance nuclear power.

In June, using unusually strong language, a Moody’s Investor Service report called new nuclear power plants a “bet the farm” credit risk for the 14 utilities pursuing them.

“The nuclear power industry may be correct about wanting those guarantees, but at what risk to US taxpayers?” asks Ellen Vancko, Nuclear Energy and Climate Change Project coordinator at the Union of Concerned Scientists. “The industry assures everyone there is no risk – and some believe them.”

But industry representatives say the loan-guarantee issue is being hyped by critics and that the industry’s own funds – paid out to compensate the government – will cover any defaults.

The government’s two predictions of a 50-percent default rate are “hypothetical” and “an unsupported assertion,” according to the Nuclear Energy Institute, the industry trade association.

“There’s a misperception about the costs [of nuclear power] going up,” says Leslie Kass, director of business policy and programs for the Nuclear Energy Institute. “Yes, we did have rising capital costs – along with every other form of [energy] generation. Those costs are starting to tip back down.”

While the mantra of nuclear power was once “power too cheap to meter,” Ms. Kass admits the next generation of nuclear costs will be considerable. Even so, she contends that large nuclear plant costs compare favorably to a giant $10 billion Texas wind project pursued by T. Boone Pickens, which was recently scaled back.

ONLY NUCLEAR POWER, Kass says, can provide the sheer volume of reliable “base load” power the nation will need going forward – and meet the challenge of climate change at the same time by not emitting carbon.

The reason federal loan guaranties are needed, she says, is because Wall Street is still averse to large capital projects of all kinds. “Our challenge, like everyone [else’s] is access to capital during a recession.” she says.

Whether a nuclear project defaults depends on many factors, but often most heavily on where costs of nuclear construction are headed. Cost estimates to build a new nuclear power plant have more than tripled in the past five years, according to industry-funded reports, industry statements, and detailed studies of new nuclear power generation by a half-dozen independent researchers.

Construction delays are a huge cost. In Finland and France, nuclear-power projects are way behind schedule and over budget, suggesting potential delays and other problems for new US plant construction, says Ms. Vancko with the Union of Concerned Scientists.

Calvert Cliffs III is being built by UniStar, a joint venture of Constellation Energy Group and Électricité de France, which is 85 percent owned by the French government. With cost estimates approaching $10 billion dollars, Calvert Cliffs III is too big for its backers to fund on their own – although a spokesman says French financing could cover 15 to 20 percent of the cost, lowering the amount of federal loan guarantees that would be required.

In 2008, Moody’s put the cost to build new nuclear reactors at about $7,000 per kilowatt of capacity. That estimate would put the 1,600-megawatt Calvert Cliffs III at around $11.2 billion.

While authorized to grant just $18.5 billion in guarantees for nuclear power, the US Department of Energy last fall had applications for $122 billion in loan guarantees to build 21 proposed reactors.

Most new nuclear projects will live or die based on whether they get those loan guarantees. “We’re poised to commence early site preparation this year for the first new nuclear plant in the US in 30 years, but to be clear, we cannot move forward without federal loan guarantees,” Michael Wallace, vice chairman of Constellation Energy, said last year.

He’s still waiting. However, the goal seems nearer. Last month, the company’s Calvert Cliffs III project was selected by the Department of Energy as one of four projects entering a final phase of due diligence for a share of the federal loan guarantees.

OTHERS HAVE BEEN LESS FORTUNATE. Exelon last month dropped its application to build two reactors at Victoria County Station, Texas. Company chairman John Rowe cited a weak economy and “limited availability of federal loan guarantees.” Deep in the massive energy-climate bill now being debated in the Senate is a plan that could vastly expand loan guarantees for nuclear power.

At the National Press Club last month, Sen. Lamar Alexander (R) of Tennessee unveiled his $700 billion plan to almost double the number of reactors nationwide.

“Let’s take another long, hard look at nuclear power,” Senator Alexander says. “It is already far and away our best defense against global warming. So why not build 100 new nuclear power plants in 20 years?”

Plans are moving forward to create a new federal “clean energy bank” – a semiautonomous agency that could ladle out funding and guarantees for new nuclear power and other technologies. Such a bank would not be a bad idea, if done properly, many say. Nuclear, “clean coal,” wind, and solar energy would all benefit from federal backing. To ensure all technologies get a fair shot at loan guarantees, the House version of the bill has a 30-percent cap on the amount that any one technology could receive.

But the Senate “Clean Energy Development Administration” (CEDA) proposal does not have such a cap – which worries Sen. Bernie Sanders, (Ind.) of Vermont. His proposed 20-percent cap on the Senate

version of CEDA was swatted down in an 18-5 vote by members of the Energy and Natural Resources Committee.

Nuclear-industry backers are behind CEDA, but not the House version. “We’re not in favor of a cap because our projects tend to be larger,” says Ms. Kass, who says a cap would unduly limit nuclear expansion and tilt the playing field.

Others insist a cap is vital.

“If we want to ensure that no one technology receives the bulk of the available funding and financing, a cap on how much investment can be made in any one technology ensures a more level playing field for competing technologies,” says Senator Sanders. “It would not be good policy to allow any one energy technology to get the lion’s share of government support.”

What worries some even more than lack of a cap is how the Senate’s CEDA plan would operate with little oversight – due to a proposed exemption from the Federal Credit Reform Act that would otherwise subject such loan guarantees to the congressional appropriations process, says Autumn Hanna, senior program director for Taxpayers for Common Sense.

Under Senate provisions, the CEDA will be overseen by a nine-person board that could potentially hand out unlimited billions in federal loan guarantees for nuclear or any other eligible technology, Ms. Hanna says.

“The big story here is that nine unelected people [could get] unlimited authority to hand out these loan guarantees,” Ms. Boyd says. “That’s the big issue here.”

Click here for a sidebar on the bumpy road to nuclear energy.

(Editor's note: The original version of the article mistakenly referred to the Federal Credit Reform Act as the Fair Credit Reporting Act.)