NASA finds water ice in Mars craters

Loading...

NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter has found water ice much closer to the planet's equator than scientists believed possible.

And it's far purer than they expected, suggesting that in the recent past, the planet's climate was far more humid than models of Mars's climate history suggested.

The results, reported Thursday in the journal Science, represent the latest surprises as researchers try to understand the red planet's climate history and the role water played in it.

The announcement coincides with the release of results Thursday showing that Earth's moon has more water than scientists previously believed, though these new water deposits appear as molecules locked up in the crystal structure of minerals on the lunar surface.

Still, in both cases, water represents a key resource for exploration because it can be split into its component parts of hydrogen and oxygen, for life support and for rocket fuel. In Mars's case, it's history of climate and water could help steer the hunt for evidence of habitats – in the distant past or more recent – hospitable to simple forms of organic life.

"The surprise was that this happen at all," enthuses Ken Edgett, a researcher with Malin Space Science Systems in San Diego, Calif., and a member of the research team. He’s referring to the ability to use small-meteor craters to discover underground ice deposits.

Just missed it in 1976

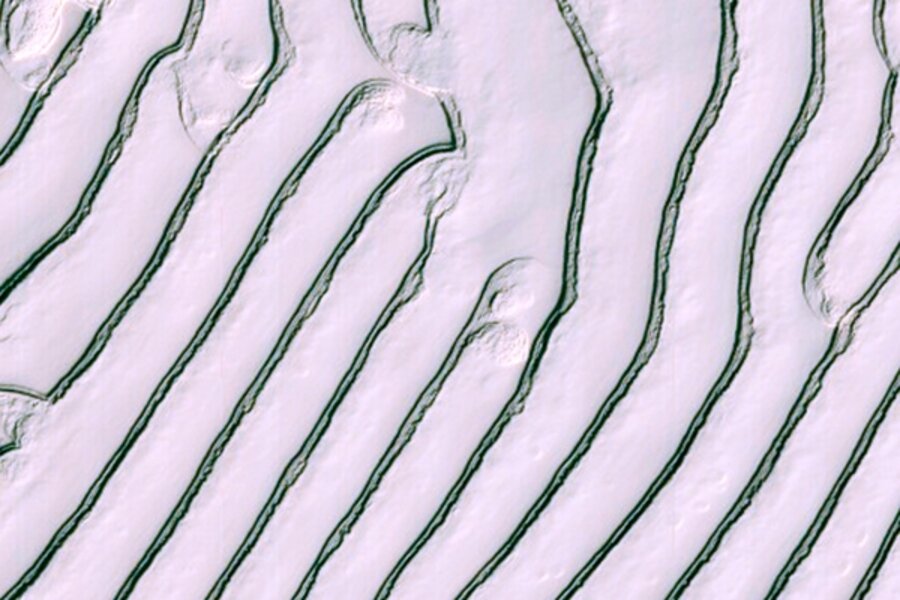

He says the ice literally came to light after the orbiter's low-resolution camera picked up evidence of five fresh meteor craters on the planet's surface. The widely separated craters appear at mid-latitudes in the planet's northern hemisphere.

Closer scrutiny showed that the impacts had uncovered a thin layer of pure ice very close to the surface – the craters ranged from only one-and-a-half to eight feet deep. Indeed, the team estimates that had the 1976 Viking 2 Lander been able to dig just four to six more inches into the soil, it would have struck ice, too. The Viking landing site is only 350 miles from the nearest ice-revealing impact crater.

Until now, researchers expected subsurface ice to form as water vapor entered the ground. When it reached cold enough depths, it would form ice between the dust grains – leading to roughly a 50-50 mix of ice and dust.

One clue that this was not the case came as the team reviewed pictures of the craters over time and saw that the ice disappeared more slowly than they expected. If the ice is half dust, the ice would disappear from view quickly as more dust became exposed. But the ice lingered in the team's images for some 200 days as it gradually changed directly from solid to gas.

The purity of the ice – estimated at 99 percent water, 1 percent dust –reopens the question of how these deposits formed. None of the extant explanations, which include a process similar to the one that generates frost heaves on Earth, seem to work in the Martian environment, says Shane Byrne, a planetary scientist at the University of Arizona in Tucson who led the team.

A damp history

Last year, NASA's Phoenix Mars Lander found pure and dirty ice farther north, adds Washington University researcher Selby Cull, another member of the team. At the time, researchers figured that the clean ice was the oddball.

"Now we see multiple instances of very pure ice" over wide swaths of the Martian surface. "It looks like pure ice is the norm and dirty ice is the anomaly."

Finding such large amounts of pure ice father south than models indicated point to a damper atmosphere some 10,000 years ago, when changes to Mar's orbit triggered a large-scale retreat of ice toward the poles, the researchers say.

The team estimates that the atmosphere back then held up to twice as much moisture as it does today.

This doesn't directly address the issue of habitats. But it does provide a reality check on the models researchers use as "way back" machines to try to reconstruct the planet's climate history.

---

Click here to find out more about the new findings of water on the moon.

---

Follow us on Twitter.