Chances are that, right now, you can spot a half dozen plastic items without even having to turn your head. In fact, if you're wearing glasses with lightweight or scratch-resistant lenses, chances are that everything you see is, in a sense, plastic-wrapped.

Leo Baekeland, the Belgian-born chemist who in 1907 developed the first plastic, probably did not set out to dominate your visual field with his creation. His original goal was much more modest: to find a replacement for shellac, a resin secreted by a South Asian scale bug.

Baekeland's "Novolak," a combination of formaldehyde and phenol – an acid extracted from coal tar – failed to catch on as a shellac substitute. But he noticed that by controlling the temperature and pressure applied to the two compounds (using a massive iron cooker that he called a bakelizer) and by mixing it with wood flour, asbestos, or slate dust, he had created a material that was moldable yet robust as well as non-conductive and heat-resistant. He dubbed his invention Bakelite, and referred to it as "the material of 1,000 uses."

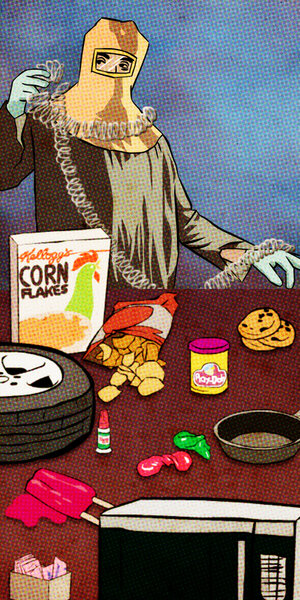

He underestimated its potential by several orders of magnitude. In the following decades, Bakelite was used to make electronics components, auto parts, cameras, telephones, buttons, letter openers, clocks, radios, toys, telephone casings, billiard balls, kitchenware, rosary beads, chess pieces, and tens of thousands of other items.

Over the 20th century, Bakelite and its descendants – plexiglass, polyester, vinyl, nylon, polyurethane, polycarbonate, and so on – transformed the stuff that our world is made of, from natural to synthetic. Items that were crafted from wood, ivory, or marble, are now affordable for almost everyone.

Yet at the same time, the ersatz topography that Baekeland brought forth does not always sit easily with us. As everyone who's seen "The Graduate" knows, "plastic" is a powerful synonym for "inauthentic." What's more, most petroleum-derived plastics will remain in the environment for centuries, if not millennia. We've replaced materials that are timeless with one that simply lasts a really long time.