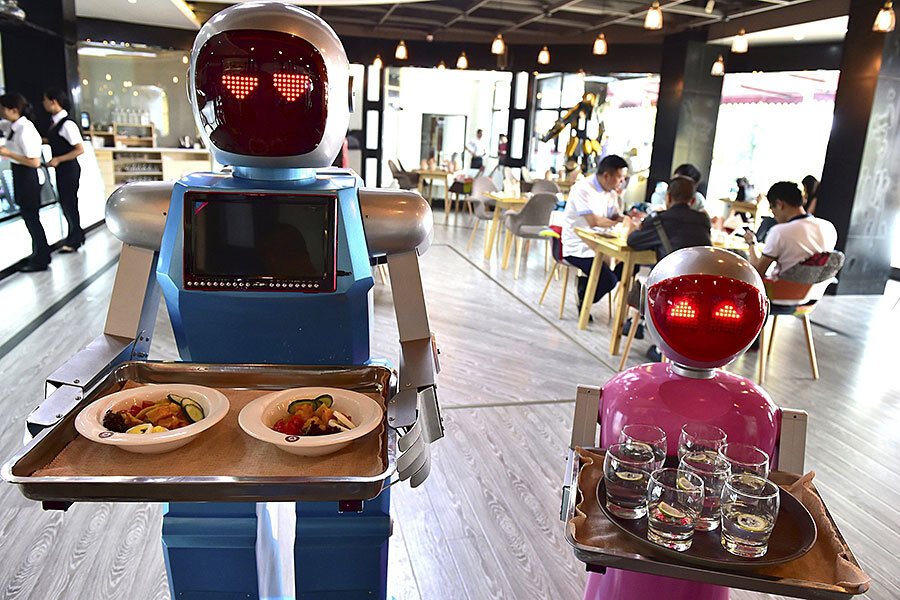

Survey: 'Machines will take jobs – just not mine'

Loading...

We, the people, expect most jobs to be commandeered by robots and computers within the next 50 years, yet we also think our own jobs will be safe, according to a new survey.

The study, published Thursday by Pew Research Center, consulted more than 2,000 people in all 50 states, as well as Washington, D.C., from a broad range of backgrounds and occupations.

Can the apparent paradox be explained?

“Partly it’s something you see in public opinion a lot: people tend to be more optimistic about their personal situation, compared with the societal level,” says Aaron Smith, associate director of research at Pew, in a telephone interview with The Christian Science Monitor.

Specifically, the study, conducted in June-July 2015, found that “65% of Americans expect that within 50 years robots and computers will 'definitely' or 'probably' do much of the work currently done by humans.”

Yet 80 percent of respondents also felt that their own jobs or professions would remain “largely unchanged and exist in their current forms” over that same time frame.

“You know the story about how people hate Congress in general, but think their own Congressman is doing a great job?” Frank Levy, professor emeritus at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, who works on technology's impact on jobs and living standards, asks in a telephone interview with the Monitor. “I think that’s an appropriate analogy.”

Yet even among professionals who analyze technology, there is almost no consensus on what the future holds, as demonstrated by a 2014 Pew Research Center survey of "experts and stakeholders," who offered predictions ranging from one extreme of the spectrum to the other.

One of the concerns that did emerge, however, as Mr. Smith of Pew highlights, was that our social systems are not preparing in any meaningful way for the possibility of a huge loss of employment as machines take the place of human workers – with the result that, if and when it does happen, we simply won’t be ready.

This survey mirrors that concern.

“But honestly, I think it’s good,” says Wendell Wallach, scholar at the Yale Interdisciplinary Center for Bioethics, and author of "A Dangerous Master: How to keep Technology from Slipping beyond our Control," in a telephone interview with the Monitor, “because I think some projections are overdone and melodramatic.”

“There’s concern the public are getting frightened of machines; it’s nice to see they’re not. This survey shows a more balanced perspective than some would suggest.”

Yet Mr. Wallach also admits that automation has already changed so much about the workplace.

He gives the example of a robot used in hospitals to lift patients from their bed, spending all day doing that one, simple task – yet the impact can be more nuanced than may at first be apparent.

The machine relieves orderlies of the exhausting task of heaving people from beds, but as a consequence, it also reduces the opportunities they have of observing or interacting with the patients. And, inevitably, it will mean fewer orderlies are needed.

“Indeed, most professions will not disappear completely but far fewer humans will be required,” says Bart Selman of Cornell University’s Department of Computer Science in an email interview with the Monitor.

“For each individual worker this may feel 'OK' because that worker could be the 'lucky one' still needed in the warehouse or elsewhere. However, this does make the competition for jobs much tougher and will further drive down wages.”

Another interesting aspect of the Pew survey was that people who performed physical or manual labor were more than three times as likely to express concern about machines or computers taking their jobs.

Yet this perhaps betrays a lack of understanding, as Dr. Levy of MIT points out: some physical jobs certainly can be done by machines, but others, such as plumbing, where the issues and situations are likely to be different in every house, are far too complex, too varied.

Conversely, occupations that rely on mental exertion and involve very little manual labor can be vulnerable to the power of machines, if the tasks are repetitive, structured.

“I think the big change on the horizon that people in general are not yet aware of is in terms of jobs that do not involve manual labor,” says Dr. Selman of Cornell. “We are seeing tremendous progress in [computers’] speech understanding and natural language understanding as well as computer vision. This means that it will become much easier for a client to interact with an automated system, which will put a whole range of white-collar professions at risk.”

And yet, as though to demonstrate the degree of uncertainty surrounding all these ideas, the range of opinions, Wendell of Yale points out that “the hype around artificial intelligence and robotics doesn’t appreciate how complex tasks can be to do”.

“It also doesn’t appreciate the richness, the nuance, the knowledge, the expertise that may not translate easily to a machine,” says Wendell. “There’s probably naiveté on this issue on both sides.”