A town’s bold plan to harness offshore wind

Loading...

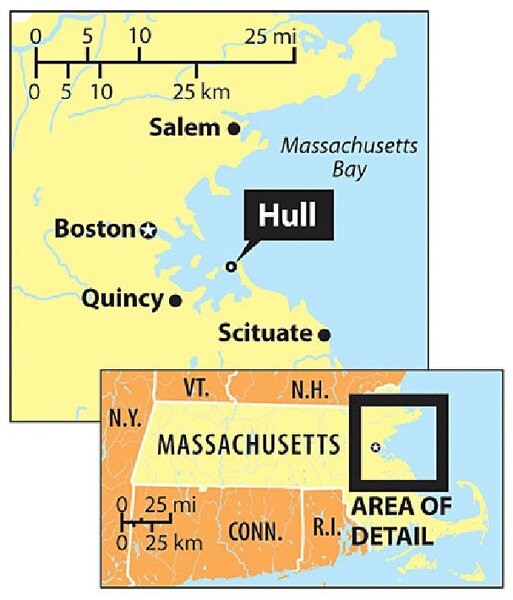

| Hull, Mass.

They would sit a mile and a half offshore from a popular beach, four 454-foot towers with blades as long as two basketball courts. If the plan gets quick approval, the town of Hull, Mass., would be powered almost entirely by wind and become the first American community with an offshore wind farm.

More than two dozen offshore wind farms have been proposed for cities up and down the East Coast and on the Great Lakes. But unlike those developer-driven plans, Hull’s effort was conceived internally. And while a much larger offshore wind project off the coast of Cape Cod, Mass., 60 miles to the south, has spurred controversy, Hull’s residents are embracing wind power.

Indeed, the town’s move has little to do with being “green.”

“It’s all about lowering our electricity bill,” says longtime resident Suzanne White, who works at Weinberg’s Bakery, a gathering place for a group of retired men who discuss town news and politics. “It’s a positive thing because eventually we won’t be able to afford oil.”

That Hull, once a popular beach town, wants to rely on wind power is a sign that the industry is gaining mainstream acceptance.

“If it can be done here,” says Town Manager Philip Lemnios, “it can probably be replicated in a lot of other places.”

A 45 percent growth in wind power

Nationally, wind power has been on a tear. The industry grew 45 percent last year and is on track to surpass last year’s growth, according to the American Wind Energy Association, pending Congress’s decision whether to extend federal tax credits for alternative energy. Now with generators already up or slated to be built on the choicest wind locations in the United States, developers are looking increasingly offshore.

Western Europe, already short of land, moved to offshore wind farms 20 years ago. They now generate 1,000 megawatts of electricity. In the US, plans are just getting under way.

Hull has a few advantages in the race to build the first offshore wind farm on this side of the Atlantic. It owns its own electric utility. And it already has two wind turbines, one near a school and one on top of a landfill. They already power 1,000 homes and the town’s traffic lights, keeping the town’s electric bills about a third below those of surrounding communities.

“For eight years, we haven’t raised the rate – and that’s huge with the cost of fuel and everything going up constantly,” says Mr. Lemnios. “We have to make sure that going forward [the offshore project] is an economically sound venture, rather than just being green.”

Sipping coffee at the Seaside Diner, a fixture of downtown Hull where diners call out to each other by name, “Sonny” Bernstein says he’s proud of his town’s twin turbines.

In Cape Cod, residents did the opposite, vocally protesting a plan to install 130 offshore generators.

But after seven years of legal wrangling and regulatory delay, that project won a court ruling this month that the developer, Cape Wind Associates, says could lead to permits being issued by the end of this year.

Leave some windy places alone, some say

Back in Hull, not everybody is sold on the offshore solution. “I think that there should be places that are off-limits – places that remain free of man-made structures, even if they are particularly windy,” says town resident and environmentalist Samantha Woods.

The sound of the turbines can keep residents up at night, says William Amico, whose family owns a house close to the onshore turbine at Wind Mill Point. “In terms of the environment, it’s a great idea to reduce pollution, but they should be a little farther away from people,” he says.