Dig the coal, bury the carbon

Loading...

| EDWARDSPORT, IND.; and DECATUR, ILL.

On the back roads near Edwardsport, Ind., jutting from a hillside carpeted with corn, a steel tower conveyer belt lifts from a mine below a black stream that spills out to become a growing mountain of coal.

Corn used for ethanol may be renewable, but coal is still king of energy crops in the boot tip of the Hoosier State. Yet if coal is to keep its crown, the phrase “clean coal” will need to be more than a slogan.

Power utilities, coal producers, and coal-rich states are racing to preserve coal’s viability as a fuel, as Washington pushes to cap carbon emissions. This region is also working to establish itself as a hub for storing greenhouse gases deep underground permanently. To do that, however, will require technology that can capture carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions from coal power plants at moderate cost.

While many environmentalists decry any further deployment of coal-based power technologies, some people say that because coal is cheap, it will continue to be used for power generation worldwide and therefore carbon capture and sequestration (CCS) technology is critical to curbing global warming.

“We have to show ourselves and others how to do this – how to slow these emissions – or it’s going to be game over,” says John Thompson, director of the Coal Transition Project of the Clean Air Task Force, a national environmental group.

At least one-quarter of the 30 billion tons or so of new human-caused CO2 emitted each year comes from burning coal to generate power, according to Emerging Energy Research, an energy market-research firm in Boston.

Although solar and wind power and other renewable technologies are expected to generate more power in the future, coal is expected to remain a dominant fuel for decades. With numerous new coal-fired power plants being built in China and India, the US must take the lead in quickly developing new ways to slash CO2 emissions from them, Mr. Thompson says. Otherwise, he notes, the world could end up experiencing what climate scientists call the “more dangerous effects” of climate change.

“If coal is to maintain its share in the global power generation mix over the next two decades, its carbon emissions must be mitigated through the capture of CO2,” says Alex Klein, research director for Emerging Energy Research.

Underground storage of carbon dioxide has been demonstrated on a small scale, but large-scale commercial viability is still uncertain, analysts say. Nearly 120 CCS projects are under way worldwide in hopes of proving its effectiveness.

Nowhere in the United States is the bid to develop CCS moving faster than here in southern Indiana, Illinois, and Kentucky – whose coal fortunes intersect where the Ohio River meets the Wabash River.

“The Midwest has got the three things you want most – deep saline aquifers to store CO2, coal for gasification, and big-city power demand,” says Kevin Book, managing director at ClearView Energy Partners, an energy market-research firm in Washington, D.C.

Also important: climate-change legislation under consideration in Congress that could, Mr. Book says, pump some $75 billion into CCS development over the next 25 years.

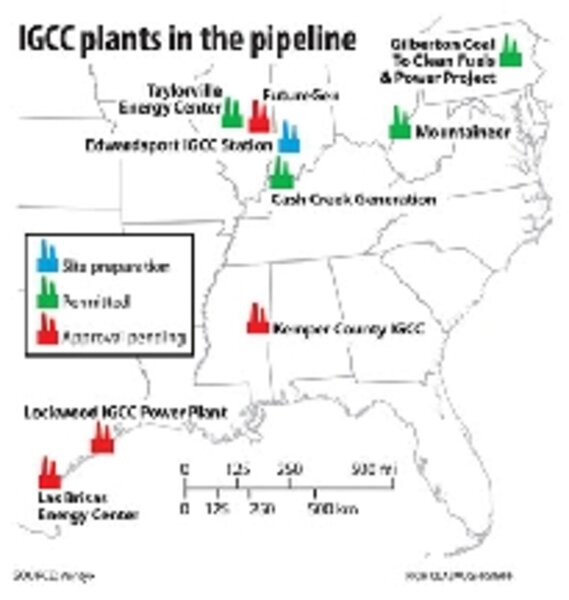

But Midwestern states are not waiting on Washington. In Kentucky, plans are moving ahead for a coal-gasification power plant. In Illinois, a consortium of businesses is racing to develop the high-profile FutureGen coal-power project, which could capture from 60 to 90 percent of its emissions and pump them underground.

In January, Illinois adopted a “clean coal portfolio” law that requires state utilities by 2015 to get 5 percent of their electricity from power plants that capture CO2 emissions and store them permanently underground. It also sets a goal of 25 percent “clean coal” by 2025.

But first, researchers such as Sallie Greenberg, an environmental geologist with the Illinois State Geological Survey, need to prove that the geology can hold CO2 under pressure in perpetuity.

She’s standing here in what was a Decatur, Ill., farm field, on a mud-and-gravel platform where a massive steel cap sits atop what could be the nation’s first commercial-scale CO2 injection well.

In April, researchers will begin pumping 1,000 tons of CO2 a day more than 6,000 feet into a porous sandstone layer far below aquifers that provide drinking water. That layer, known as the Mount Simon, should hold the CO2 for eons beneath a 300-foot shale cap, she says.

“We will monitor this site for at least three years and know in some detail whether or not CO2 is escaping,” she says. “But we think the geology shows a high likelihood the CO2 will stay down.”

Similar tests have been conducted elsewhere. But only pumping much larger amounts of CO2 will prove whether it will stay put. Initially that CO2 will come from a nearby Archer Daniels Midland ethanol plant. By sequestering about 1 million tons of CO2 from ethanol over three years, the project will show if the same could be done for power projects – or any CO2-intensive industry, says Rob Finley, director of the Illinois State Geological Survey Center for Energy and Earth Resources.

Success here could mean a boon for CO2 sequestration from ethanol, cement, and manufacturing plants. It could also support an expansion in mining Illinois’s high-sulfur coal – if carbon dioxide and other pollutants, like sulfur, can be removed inexpensively, says Warren Ribley, director of the Illinois Department of Commerce and Economic Opportunity.

There are other options for using the captured CO2: Plans are afoot to run a pipeline from Illinois to Mississippi, where CO2 could be pumped underground to extract oil remaining in depleted fields.

All of this hinges on capture technology, which accounts for three-quarters of the cost of CCS today. The leading technology is integrated gasification and combined cycle (IGCC), which adds 20 percent to the cost of building a new power plant but lowers the cost of removing carbon dioxide from the plant’s exhaust.

Here in Edwardsport, in a quarter-mile-wide bowl of mud, cranes, and concrete, workers are bolting together the world’s first large-scale commercial IGCC power plant. On track to begin generating by 2012, the new $2.3 billion plant – being built by Duke Energy with $460 million in local, state, and federal tax incentives – is being watched closely by lawmakers, environmentalists, and the energy industry.

When it opens, the plant should be the cleanest coal power plant in the nation, company officials say. More important, if it receives state approval as expected, the plant will, as early as 2013, also begin capturing up to 1 million tons of its own CO2 annually and pumping it underground.

“Whether we’re producing steel or generating electricity, it’s all heavily carbon intensive,” says David Pippen, policy director for energy, environment, and natural resources for the governor of Indiana. “We feel that for some time to come, our nation is going to produce CO2. So, to the extent we in Indiana can sequester it, we want to be part of the solution.”

But not everyone is persuaded that CCS is necessary or safe. In a study last year, the environmental advocacy group Greenpeace declared CCS “unproven, risky, and expensive.” Leakage of just 1 percent of CO2 from storage would undermine greenhouse-gas reduction programs. Renewable-energy development might suffer, and CCS could raise concerns about human health, ecosystem damage, and groundwater contamination.

The Natural Resources Defense Council applauded the House of Representatives’ passage of a climate-energy bill that contained billions for CCS, but others say that the spending was a sop to win coal-state votes – and poor environmental policy.

Energy efficiency; wind, solar, and geothermal power; and a more efficient power grid can meet US and global energy needs, according to Friends of the Earth in Washington. Opposed to the climate-energy bill and to CCS, the group favors a moratorium on new coal-fuel power plants.

“Instead of developing CCS capability, we should move away from coal altogether,” says Nick Berning, a Friends of the Earth spokesman. “Even if [cost and liability] concerns were overcome, you would still have the problem that coal mining and mountaintop removal is an inherently dirty process. We don’t need it.”

Needed: a retrofit breakthrough for coal power plants

Building new coal power plants that capture and sequester their own greenhouse gases would not by itself capture enough CO2 to cool the planet, a new report says.

Still to be invented is a cost-effective carbon-dioxide-capture technology that can be retrofitted to existing conventional coal power plants, a Massachusetts Institute of Technology study says.

There is no credible pathway toward prudent greenhouse gas stabilization targets without CO2 emissions reduction from existing coal power plants,” said Ernest Moniz, director of MIT’s Energy Initiative program in a statement. “These coal plants are going to continue to operate for decades....”

Fewer than half of existing coal-fired plants are large enough or new enough to justify such a retrofit using current CO2 capture technologies. Even if retrofits are affordable, applying them creates a dilemma: The technology gobbles up much of the power plant’s capacity, so extra power is needed from – where? Another coal-fired plant? Renewable energy?

Nationwide, about 320 coal-fired generating units could use such retrofits, according to Ventyx and E3 Consulting, two power industry consulting firms. That would cut 55 gigawatts of generating capacity – a one-sixth drop in the nation’s 310 gigawatts of capacity from coal.

Kevin Book, managing director for Clearview Energy Partners, puts it this way: “The breakthrough we don’t have yet is an affordable retrofit technology. We had better invent something soon.”