What the future of the auto industry will look like

Loading...

| Washington; and Anderson, Ind.

John Waters is leaning against a vehicle that looks like a delivery van as imagined by Pixar Animation. The IDEA – that’s its name – is blocky, yet curved, with wheel skirts and a little upswoop at the back that adds attitude. You can almost hear it speaking in a chirpy cartoon voice.

Inside IDEA’s silver sheet metal is plug-in hybrid technology that will power it an estimated 100 miles on a gallon of gas. If Mr. Waters has his way, thousands of these cuddly vans will soon be double-parked all across America, blocking travel lanes while their drivers wait for someone – anyone! – to sign for these darn packages, please.

Years ago Waters worked on General Motors’ legendary EV1 electric car program. Now he’s president and CEO of Bright Automotive, an Anderson, Ind., start-up that’s recruited many EV1 veterans to help develop a new generation of hybrid trucks and cars.

“It’s the wealth of experience of our people that will make this work,” he says.

One hundred and one years after the debut of the Model T, the automobile – and the iconic industry that produces it – may be on the cusp of changes as profound as any ever wrought by Henry Ford.

Detroit is in crisis. The Big Three is no more. In the wake of recession, GM’s and Chrysler’s bankruptcies, and Chrysler’s merger with Fiat, the traditional Michigan-based automakers now might better be called the Medium Two and One-Half.

Meanwhile, a new generation of auto entrepreneurs is rising, committed to building greener modes of transportation in new ways. They’re scrambling for billions in government aid intended to jump-start production of vehicles that burn little gasoline – or no gasoline at all.

Plus – and this sounds odd, given the current emptiness of US showrooms – the auto industry may be about to see its biggest growth spurt ever. Developed nations choke on traffic, but in the rest of the world hundreds of millions of consumers yearn for their first set of wheels.

Brazil, Russia, China, India, and Indonesia are among the rapidly emerging countries where per capita incomes are at or near the level at which auto ownership typically takes off. Consulting firm Booz & Company predicts the world will have 1.5 billion cars in use in 2018, up from 672 million today.

Who will produce those vehicles? What will they look like? These questions will help shape some of the industries of tomorrow, and, along with them, the economies of nations. For now, new firms such as China’s Geely and India’s Tata are now rising to challenge the founding titans of the horseless carriage.

“The global auto industry is still developing,” says Bruce Belzowski, an associate director at the University of Michigan’s Transportation Research Institute. “In five to 10 years, there could be strong competition on a global scale.”

ANDERSON IS ONE of those Midwestern towns where modern automobile technology was born. Flint, Mich., had its engine and body shops, and Detroit its production lines, but Anderson provided cars with the beat of their electronic heart.

By 1900, Anderson was home to 11 automakers and two brothers, Perry and Frank Remy, whose Remy Electric would soon become the nation’s leading producer of magnetos and dynamos needed to start cars in the nation’s growing auto fleet.

Through the decades, legions of electrical engineers worked at Remy and at other nearby manufacturers to develop power for lights, radios, seat warmers, keyless remote entry fobs, and computer-controlled engine and ventilation systems. Anderson and the rest of central Indiana was the “Silicon Valley” of vehicles, says William Wylam, a former director at Delco Remy, Remy’s successor firm.

That’s “was,” as in, “isn’t any longer.” Today Anderson, a city of 60,000 northeast of Indianapolis, mixes run-down bungalows and shuttered storefronts against the backdrop of an empty 1960s-era headlight factory. “Everything here in Anderson today is gone – it’s all gone and most of the [factory] buildings are torn down,” says Mr. Wylam.

Well, maybe not everything. A little company out by the state highway, Wylam adds, is mining the area’s biggest remaining resource – its rich vein of human talent.

That firm is Bright Automotive. A number of its key people used to work at GM’s Indianapolis research center, which developed the EV1, the first modern production electric vehicle from a major automaker. Introduced in 1996, the EV1 was available in California and Arizona, via lease. GM discontinued it in 1999, citing program expense. It recalled the cars. Most of them were crushed. But the EV1 engineers’ dreams weren’t crushed with them.

“These are highly qualified, highly motivated people,” says Wylam. “I wouldn’t want to get in their way.”

The IDEA is Bright’s main project. Working from a gleaming office park on the edge of Anderson, the Bright team has put together a prototype of the vehicle, which combines plug-in hybrid technology with extensive use of aluminum, carbon fiber, and other weight-reduction techniques.

Regular hybrids, like today’s Toyota Prius, use an electric motor and a small internal combustion engine. Plug-in hybrids use that technology, too, but with a big battery and big electric motor, plus – surprise! – a plug. They also recharge their batteries by plugging into the regular electric grid.

Waters says the IDEA will get around 100 miles of city driving for every gallon of gas. It’s van-size because the company figures it could win over bean counters at companies pressed by high fuel costs, such as FedEx, UPS, and the US Postal Service.

But if the company is to turn out 50,000 of these swoopy things a year by 2012, as it plans, it needs cash – and today investment dollars are hard to come by. So Bright has turned to the federal government. The firm has applied for $35 million in grants from the stimulus bill, as well as a $450 million loan from a Department of Energy green technology program.

Bright is hardly the only US firm with an idea like IDEA. At least a half-dozen start-up companies, with names like Aptera and Visionary Vehicles, are vying for funding to build the next-generation automobile.

Many – probably most – won’t survive. That shouldn’t be surprising, as firms rose and fell in the early years of the internal combustion engine, too. Who today remembers the Mercer Raceabout, or Essex, or Nash Statesman? All were cutting-edge cars in their heyday. But their heydays all turned out to be brief.

Of course, nothing is certain about the auto industry these days. It is shaking to its very foundations. Toyota is losing money. A niche Swedish sports-car maker has bought country icon Saab. Hummer has become less fashionable than Hyundai. Chrysler’s next model may be based on the Fiat 500, a car so small that it looks like a Dodge Charger’s lunch.

Then there is General Motors, ward of the state. Those who remember GM as the producer of such iconographic autos as the 1957 Bel Air may see its fall as a shame. Those who bought the awful 1970s Chevy Monza (or its evil twin, the Oldsmobile Starfire) may consider its bankruptcy well deserved.

The US government has already invested some $80 billion in tax dollars in GM and Chrysler. It probably will be at least a year before the Treasury can even begin to plan when it might sell government-owned shares in the company to recoup that cash.

Will the US ever get that money back? There are “reasonable scenarios” under which the taxpayer investment will be returned, said Ron Bloom, President Obama’s high-profile auto adviser, at a June 10 Senate hearing. “But by no means would I say that I am highly confident that will occur.”

That does not sound like a ringing endorsement, does it? Postbankruptcy, both GM and Chrysler will be shorn of debt and overhead, and theoretically will be better able to compete in a tough market. The key may be to what point US sales recover.

In January, the pace of vehicle sales in America fell below 10 million units annually for the first time in almost three decades. Some analysts see sales staying in a trough for years, as newly frugal consumers learn to do without leased Audi Q7s, and turn to the used-car market, or (gasp!) keep driving their old cars instead.

Others think that is too pessimistic. In the US, about 13 million cars a year are scrapped due to advanced age, according to the International Motor Vehicle Program, a research consortium founded at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 1979. (Aren’t the Monzas all gone by now?)

That loss might put a floor under demand. “The global auto industry will recover to pre-crisis levels as the global economy recovers: There is no paradigm shift at hand,” says a recent research paper from the IMVP, a nonprofit funded by donations from auto firms, as well as other sources.

POST-TROUGH, THE U.S. AUTO industry at least will look a little greener. Besides start-ups, the traditional US automakers are moving to hybrid models. Ford’s new Fusion hybrid is doing well in showrooms today, relatively speaking. GM is making a big deal out of its forthcoming Chevy Volt, an extended-range plug-in hybrid that will be available next year.

Mr. Obama wants 1 million plug-in hybrids on US roads by 2015. By 2016, the US will require automakers to produce fleets of vehicles that get an average of 35.5 miles per gallon, up from today’s figure of 27.5. The federal government is poised to spend billions on everything from new lithium-battery plants to incentives for consumers to buy more-efficient cars.

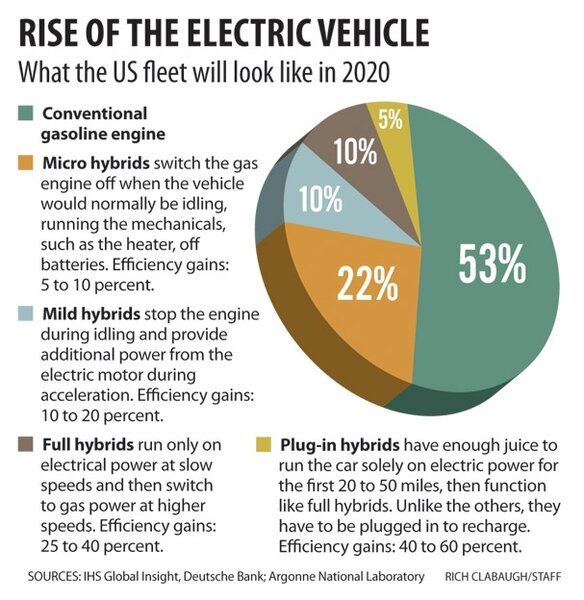

A new generation of electric cars, as a result, is moving toward showrooms. In the US, 13 hybrid models were available in 2007. By 2011, at least 75 will be on dealer lots, Deutsche Bank reported last year. IHS Global Insight, a consulting firm, projects 47 percent hybridization of the US market by 2020. In Europe, where fuel economy requirements are tougher, the transition could be even more dramatic: Roland Berger and J.D. Power estimate that the market for hybrids/electric vehicles could rise to 50 percent by 2015 – up from 2 percent in 2007.

Is the gas-powered V-8 about to become as extinct as 8-track tapes?

“What we are seeing today is a major shift toward electric-drive vehicles,” says Dan Sperling, director of the Institute of Transportation Studies at the University of California, Davis.

Well, maybe. Other experts point out that Obama’s goal of 1 million hybrids is quite modest, given that even in this constrained year US consumers will drive away 9 million new vehicles.

The problems are habits, and costs. Consumers have been driving gas cars – and big ones, in the US – for a century. Most of them are not going to pay more to try something new.

And electric-drive cars are more expensive, at least for now. Batteries are costly, for one thing. Chevy’s Volt will probably have a sticker price near $40,000. Unless government policy offsets this green price penalty, hybrids and their ilk could remain a niche product in the short to medium term.

“In five years, if fuel prices don’t do anything crazy, the product mix will look pretty much like it does today,” says Daniel Snow, an assistant professor at Harvard Business School who studies the application of new technology.

Gas prices might do something crazy, of course. They’ve roller-coastered quite a bit recently. At last summer’s $4 per gallon, consumers fled big vehicles. Hybrids were hot – but so were four-cylinder economy cars. And, technically speaking, conventional gas autos still have lots of leeway for mileage improvement. Direct fuel injection, use of lighter weight materials, and other techniques could improve efficiency by 20 percent or more.

“There isn’t any part of the vehicle that will remain untouched by the search for better mileage,” says Paul Lacy, manager of technical research, Global Automotive Group, at IHS Global Insight.

In the longer run, the power source of a vehicle may depend on its intended use. Runabout cars for shopping and school drop-offs could be straight electric. Commuter vehicles that take longer trips downtown might need the extended-range capability of a hybrid. Long-distance cruisers meant to travel at high speeds from, say, Tucson, Ariz., to Tucumcari, N.M., might operate best with advanced diesel-fueled spark-ignition engines.

Cars, in other words, will still be around – for a long time. That is easy to forget now, particularly in the US, as GM stumbles and the price of gas heads for its next unpredictable destination. Mass transit is great, but the auto is one of history’s revolutionary technologies. People everywhere want the freedom inherent in a personal set of wheels.

Given the number of people in the developing world who can now afford a basic auto, or will soon be able to, the global vehicle industry may not yet have seen its period of greatest growth. “The motor vehicle manufacturing industry, which is 100 years old, is only now emerging from its infancy,” conclude Ronald Haddock and John Jullens, analysts at Booz & Company, in a recent report.

Once a nation’s gross domestic product reaches $10,000 per capita, its rate of automobile ownership accelerates, according to Booz & Company data. Among those countries that have not yet reached that point, but will soon, are Russia, India, China, Malaysia, Indonesia, and Iran.

The bottom line: Even given the recession, world auto sales could total 715 million units over the next nine years. And the most important attribute a car can have in this new global market may not be electric drive or plug-in technology, but low expense. When a farmer from rural China goes looking to upgrade from his motorbike, the first thing he’ll look for is something he can afford.

That is why the Tata Nano is such a big deal. It is the world’s cheapest production car, with a price tag of about $2,500. No, its trunk does not open. (Access is from the inside.) Engineers shaved costs by attaching wheels with three lug nuts, instead of four. It looks like a beanbag chair, or possibly a large kitchen appliance. But when its Indian manufacturer, Tata Motors, began taking orders for the car this spring, it sold 200,000 in 16 days.

Demand for low-priced vehicles around the world soon will be huge, says Hiroshi Hasegawa, president of SC-ABeam Automotive Consulting in Tokyo. And that business may not go to Buick or Volkswagen or Toyota. Even in Japan, young adults now covet cellphones as status items but see cars as simply a way to get around. “I would expect Chinese and Indian low-priced cars to meet such demand,” says Mr. Hasegawa.

In the 1970s, Japanese automakers invaded the US and Western Europe with efficient small cars, tapping a market the locals did not know existed. Now, those same manufacturers may be planning for a different kind of global competition, in which many more firms than before take part. “We expect to move into a multipolar age,” says Hasegawa.

And what part of this market do the Japanese want to predominate in? Yep – hybrids and other electric-drive vehicles. Toyota and Honda beat US firms to the marketplace with hybrids, and they are not eager to cede that ground to anyone – even an eager upstart like Bright Automotive, with its friendly 100-mile-per-gallon van.

Toyota expects that by 2020, hybrids will account for more than 20 percent of its annual sales volume.

“Japanese carmakers acquired technologies and production know-how on [hybrids and electric vehicles] a long time ago,” says Koji Endo, an auto analyst with Credit Suisse in Tokyo. “They will continue to improve their techniques while cutting costs in the next five years.”

Takehiko Kambayashi contributed from Tokyo.