Waterless urinals: Cheap. Green. But many think ‘gross’

Loading...

Sanitary fixtures in men’s rooms don’t make for polite conversation. Nor would many people want to read about them over a morning cup of coffee.

But it’s Jan Aceti’s job to encourage people to think about them.

As principal of consulting firm Aceti Associates, Ms. Aceti tries to spread the word about “waterless” urinals, an environmental innovation that she hopes can ease the world’s water problems.

Fresh water is a dwindling resource worldwide. A waterless urinal saves one to three gallons of fresh water per flush, compared with a normal model, according to a 2008 report Aceti’s firm prepared for the Massachusetts Executive Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs. In an office with 1,000 men, that adds up to 1.56 million gallons of water saved annually.

This waterless message has finally started to catch on, says Aceti.

“Can you imagine a more scenic setting for a waterless urinal?” she asks, pointing to the picture of an installation at the Taj Mahal in India.

At American ballparks, airports, and tourist attractions, waterless urinals are becoming increasingly common.

Yet despite the message of efficacy and environmental stewardship, the 15-year fight to further introduce these unorthodox urinals is far from over.

Hygiene myths abound. Many hold their noses when they hear of this no-flush system. Diverting streams of urine for use as fertilizer is another tough sell. But the industry is optimistic.

“By our estimates, less than 1 percent of the world’s urinals use these waterless systems,” says Randall Goble, vice president of marketing for Falcon Waterless Technologies in Grand Rapids, Mich.

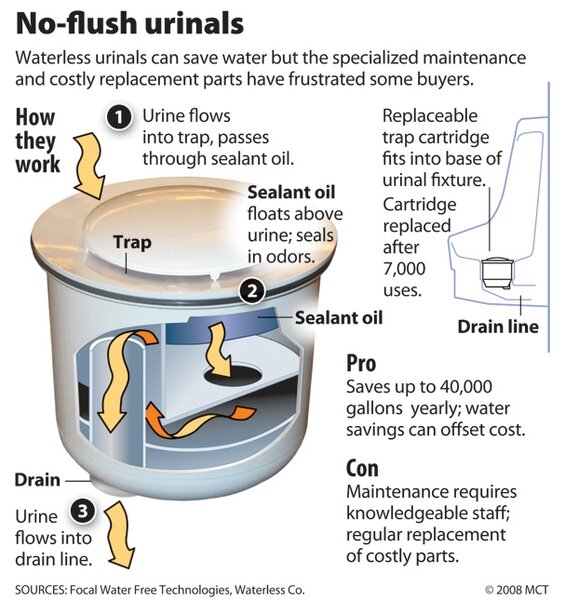

He explains that the technology behind the setup is fairly simple. A biodegradable liquid sealant, such as oil or alcohol that is lighter than water, floats on top of a conventional water-filled drain.

The barrier layer, a one-way seal, allows liquid waste to flow through but blocks sewer gases from coming back up and entering the restroom. (See diagram above.)

One of the first waterless urinals, patented in Austria more than 100 years ago, involved periodic cleaning of the waste sediment. But modern, water-fed plumbing put an end to this chore.

In the 1990s, sealant-filled cartridges for waterless urinals were introduced. “Those cartridges took the ‘ugh’ factor out of the maintenance,” says Mr. Goble.

In 2006, kitchen- and bath-fixture giant Kohler Co. came up with an optimal funnel-shaped design for the bowl, eliminating the need for disposable cartridges.

“In traditional urinals, the surfaces on the inside are wet much of the time, and you get biofilms of growing organisms,” says Prof. Charles Gerba, an Arizona State University microbiologist who has researched surface contamination in public restrooms.

Flushing further creates a spray that lands on the rim and floor, creating a breeding ground for microorganisms.

“If easily-maintainable, water-free urinals had been developed first, no one would use conventional urinals because of all the contamination they cause,” he adds.

While Mr. Gerba says that design innovations can now ensure that waterless urinals are both more efficient and more sanitary than their traditional counterparts, educating consumers and facility managers about the proper use and maintenance of waterless urinals is the key to wider acceptance, according to Shane Judd, senior manager at Kohler in Milwaukee.

“People have misgivings about water-free sanitaryware, but those who try it embrace it,” he says. Because of the aesthetic of the sleek model, green designers have started installing it in clients’ homes as well, he adds.

Most marketing for waterless urinals target organizations with environmental sustainability goals. Other groups gravitate to them for financial reasons. The waterless designs reduce operating costs and eliminate common plumbing emergencies, such as clogging and flooding, says Goble of Falcon Waterless Technologies.

“Students are known to flush anything from unwanted lunches to report cards in urinals,” he says. Also there are no flush handles that can be tampered with.

In rural regions of the third-world where sanitary infrastructure is nearly nonexistent, these urinals present the option of leapfrogging past systems that use up precious water, says Jack Sim, an advocate of compost toilets. In 2002, he launched the World Toilet Organization, a nonprofit group based in Singapore and committed to improving toilet facilities worldwide.

“Human urine is also a good and cheap source of plant nutrients,” says Mr. Sim. Farms in the developing world can use it to improve crops without buying expensive fertilizers, he adds.

In parts of the United States, wastewater treatment plants discharge liquid waste into seacoasts, says Carol Steinfeld, author of “Liquid Gold: The Lore and Logic of Using Urine to Grow Plants.”

The waste contains nitrogen that cause aquatic plants to thrive. These blooms eventually die and decompose, pulling oxygen out of the water and suffocating fish in the process.

“Much of that nitrogen is from the urine alone,” she says. “Avoiding expensive denitrification could be as simple as diverting that stream. Waterless urinals point to a direct opportunity to harvest fertilizer. Urine is usually pathogen free – unlike the brown stuff.”

As a resource recycling specialist, she designed a “Garden Urinal” for green-product company Ecovita in New Bedford, Mass. The urinal can be plumbed or directed to a self-contained planter. This waterless urinal – which can also be used by women – will be available for sale this summer. “Ornamental plants use up the nitrogen in urine, keeping it out of receiving waters,” she says.

Diverting and using urine in backyards may seem gross now, but Ms. Steinfeld predicts that the environmental benefits will eventually outweigh the icky factor.

Meanwhile, water savings from waterless urinals could be the main draw for consumers. “Why do we flush [what could be] drinking water down the urinal every time?” asks Mr. Judd, of Kohler’s Water Conservation division.

Because people have always done it that way, he says, answering his own question. “But now, with well-designed waterless urinals, there is a chance to change that.”