They cooked up recipes for charity

Loading...

During many years as an antiquarian book dealer specializing in culinary works, Janice Longone had the privilege of handling almost every major cookbook in the world.

But however splendid or treasured some of those volumes were, it was a far humbler category, known as charity cookbooks, that captured her heart. Published by women in nonprofit groups across the country, these fundraising books have been rolling off American presses since the Civil War, benefiting churches, schools, libraries, sororities, cemetery associations, the homeless, and others in need. Some also gave heady new power to the women who produced them.

"No matter what the specific cause for which the women raised funds, the underlying purpose began as women helping other women to help themselves and the outside world," says Mrs. Longone, now curator of American culinary history at the University of Michigan's Clements Library in Ann Arbor. She considers them "an integral part of the history of the women's movement."

To honor the unheralded role of charity cookbooks, Longone has assembled more than 100 early examples at the Clements Library. Called "The Old Girl Network: Community Cookbooks and the Empowerment of Women," the exhibit will remain on view through Oct. 3.

These grass-roots books serve several purposes. "They preserve America's culinary heritage by region," Longone says. They also offer a record of American social history, including the suffrage and temperance movements.

The first known charity cookbook, "A Poetical Cook-Book," appeared in 1864. It featured rhymed recipes and raised money to support those wounded, widowed, and orphaned by the Civil War.

"Because so many men were away, women began to do things they had not done before," Longone says. "They found their own space and place. You see this ferment bubbling over of women working together." As they collaborated, women honed valuable business skills. "They had to hire printers, test recipes, go out and get ads, and work on a distribution system."

After the Civil War, as women turned their charitable attentions to causes such as suffrage, education, and improved working conditions, cookbooks became one of their most effective weapons. "There was always opposition to women organizing," Longone says. "But men probably thought, 'It's only a cookbook.' "

When "The Woman Suffrage Cook Book of 1886" was published, women sold copies at the fairs and bazaars they staged to raise funds for this cause. Other suffrage cookbooks followed. Most contained pro-suffrage quotes from famous people. One volume tucks a quote from John Greenleaf Whittier between recipes for cucumber relish and orange pudding: "For 50 years I have been in favor of Woman's Suffrage. I have never been able to see any good reasons for denying the ballot to women."

Even advertising in the cookbooks promoted women's independence. After women won the vote in 1920, the "Virginia Cookery Book," published by the Virginia League of Women Voters in 1921, featured an ad for Mass. Mutual Life Insurance Co. It reads, "You have been fighting many years to secure Equal Rights. This company gives you Equal Rates!" Women ran ads too, offering to teach piano or make millinery and corsets.

Charity cookbooks also benefited the temperance movement. Explaining women's interest in that cause, Langone says, "They felt those most hurt by drunkenness were women and children."

For Merinda Hensley, a librarian at the University of Illinois in Urbana-Champaign, interest in the genre began when she was a graduate student. The university had received a donation of 6,000 cookbooks. As she went through the boxes, she realized that the most interesting were community cookbooks.

When community cookbooks – another term for charity cookbooks – began in the 1860s, women "had no political power and very little power in the home," Ms. Hensley notes. "But they took what they knew, which was cooking, and raised money, which was power, and turned that back into their communities for things that were important to them."

One bibliography of charity cookbooks that were published before 1916 lists almost 3,000 titles. "Three-fourths of those are known around the country as having one copy only," Longone says. "It shows how scarce they are. Very early ones are very expensive now. Some go for $3,000."

Earlier works are especially fragile. "Because they're published in very small numbers, on very cheap paper, with cheap bindings, they degrade very easily," Hensley says.

Two early volumes have remained in print for more than a century. "The Settlement Cookbook" was published in 1901 by the Jewish Settlement House in Milwaukee. Since then it has gone through four revisions, 34 printings, and 2 million copies. "For 75 years every charity in Milwaukee received financial aid from selling this book," Longone says.

"The Buckeye Cookbook," published in 1876, is still in print as well.

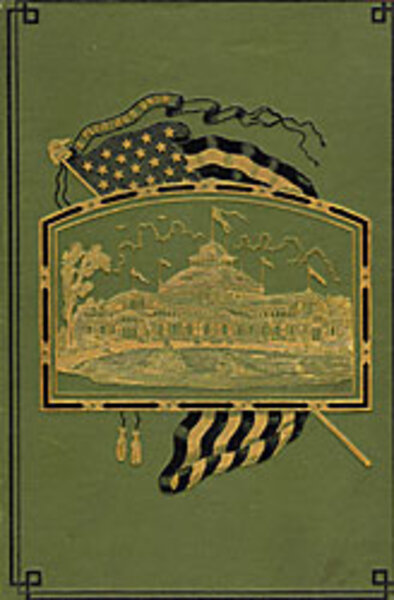

Longone ranks "The National Cookery Book," written for the 1876 World's Fair in Philadelphia, as her favorite charity volume. "It was the first national cookbook for America," she says.

Recipes – or "receipts," as some books call them – can feature quirky names, such as Rinktum Diddy, Mother's Election Cake, Kiss Pudding, and Newburyport Housekeeper's Way to Glorify Cold Mutton. Early books also offer household tips. One suffrage cookbook tells how to "Destroy Ants, Preserve the Complexion, and Cleanse Soiled Ribbons and Laces."

Today, half a dozen companies and schools help groups make their books more professional. There's even an annual competition, the Tabasco Community Cookbook Awards, honoring cookbooks published by nonprofit groups.

"Many books used to be mimeographed recipes compiled in the church basement," says Jan Hazard, a former food editor who serves as a judge for the awards. "Now some look like coffee-table books, they're so pretty."

Praising the role charity cookbooks play in chronicling and preserving local culinary traditions, Hensley says, "It's a window to our past. Politically, women have contributed to our economy for over a century through these books. ... They used what they had to make the world a better place."