Can you outsource this? The brainy copy editor behind the headlines

| Baltimore

Let’s pretend, for just one paragraph.

Imagine that Walter Burns, the tyrannical managing editor from the famous play, “The Front Page,” magically materializes in the real world. While here, he gets into one of his foaming rages and sentences John McIntyre to life in the purgatory of all newspapers, that graveyard for overused reporters, the copy desk. Mr. McIntyre accepts his fate willingly, gratefully, grinningly, happily: It is what he wanted.

Now, back to reality. Burns remains a deathless character in a fictional story about newspapering. McIntyre is alive and enjoying the game that H.L. Mencken once defined as “the life of kings” – or close to it: He’s on a big-city newspaper, lord of the copy desk at The Baltimore Sun.

In 2006, Mrs. McIntyre baked her husband a cake to mark his two decades running the staff that provides the ultimate screening of the newspaper’s content, the final edit before it hits the streets and doorsteps of Baltimore. With his colleagues, McIntyre ate his cake, and he’s had it, too.

“I can’t imagine anything I would have liked more,” he says. “I love editing. I love news. I love the collegiality of copy desk work.”

Has he truly found his calling?

“Those who do not edit do not understand the keen pleasure that comes from taking up a text and leaving it tighter, clearer, and more accurate. Working against deadline provides a structure and a stimulus. And it is far from widely understood how smart and funny copy editors are as a group.”

This last sentence is intended to rebut the conventional perception people have of these journalists as undemonstrative, timorous folk who analyze and argue over the efficacies of commas and semicolons and such, and throw boring parties. McIntyre is an unequivocal man, faintly theatrical, occasionally pedantic, a touch pompous. A former colleague describes him as “the ultimate fuddy-duddy, who knows his grammar back and forth,” adding, “he dresses like a floorwalker, flower in his lapel and all. But he is respected.”

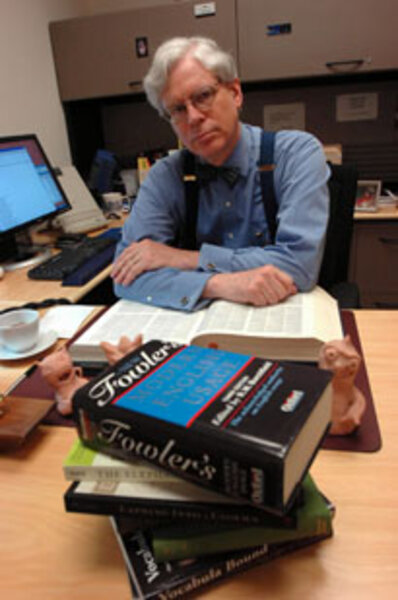

He sits comfortably in his minute office within the Sun’s immense newsroom, thinly populated these days. Lean and tall, his head of wavy white hair is seemingly attached to the rest of him by his signature bow tie. He wears suspenders. A white tea set suggests his moderate Anglophilia. The office itself bespeaks orderly management: CDs and books line shelves; muted notes of Franz Joseph Haydn drift on the air. His desk is clear — until he drops a thick pile of papers onto it, copies of the 400 postings he has made on his Baltimore Sun blog, “You Don’t Say.”

“Everything I know about language and editing is in these pages,” he says. And more: The blog is the man, a collection of his many parts.

A short posting early this month revealed McIntyre’s thoughtful embrace of globalization. Having observed that Scout, the narcoleptic family cat, is shirking his duties, probably having to do with mice, McIntyre is letting him go and outsourcing the cat’s work to India.

His filmed instructions on managing bow ties suggest fine sartorial taste, as well as his desire to teach, or to perform, or both at the same time.

Thoughtful moments bring serious topics to the blog: a eulogy for the men and women who once contributed to the miracle of production that is the daily newspaper. McIntyre shines a light on the “lost crafts,” those of proofreaders, typesetters, linotype operators – all gone now, brushed aside by a technology both irresistible and indifferent. He writes of “the ugly realities of the metropolitan newspaper” as it is today.

Though seemingly satisfied in his current surrounding, McIntyre is weighted with unpleasant recollections of earlier experiences with editors and reporters who expressed contempt for the copy desk. One described their work as “a necessary evil.” Another didn’t even know the names of the copy editors, “couldn’t have picked them out of a police lineup.” He remembers a reporter who, early in his career at the Sun, “flew into a rage and called me a liar.”

Such behaviors made clear the want of respect for those whose job is to catch the errors and smooth the wrinkles of the stories that come under their scrutiny each day.

Having been at this game for 28 years, at the Sun and earlier at the Cincinnati Enquirer, McIntyre says he understands the dynamic that separates copy editors from reporters and from managers who used to be reporters.

“Nobody likes to be edited,” he says. “People understand that when they see a copy editor approach, it’s not good news.”

This disrespect, he believes, flows from the ignorance among many reporters of what copy editors do: They correct grammar and spelling; they check facts to assure accuracy; they may even clarify the reporter’s prose, frequently shot through with mistakes owing to the pressure of deadlines. They caution unappreciative writing colleagues who are moving toward the edge of libel or slander.

“The most important question a copy editor can raise to a reporter,” says McIntyre, “is, ‘Are you sure you want to do that?’ ”

Which is not to suggest that copy editors are infallible. McIntyre’s desk once allowed a map to get into the paper that labeled the Pacific Ocean as the Atlantic, and vice versa.

This old schism within the newsroom has produced more than its share of bent perceptions: Copy editors are introverts, nerdy, self-effacing bookworms, though probably a little more contemplative than reporters. They are abrupt, ambitious, maybe even impulsively desperate for attention. As with most hoary presumptions and stereotypes, this one holds some truth.

McIntyre believes that relations have improved in recent years: “The open scorn is a thing of the past.” But there are broader concerns. His craft, and those who practice it, “are imperiled by shortsighted cost cutting and ignorance [that word again] of its value.”

With print journalism in decline and newspapers desperate to reduce staff, copy editors worry, and with reason. McIntyre has 39 copy editors beneath him. Eight years ago he had 58. Currently the Sun is processing the early retirement or layoffs of about 100 employees. Half are likely to disappear from the newsroom.

Signs that copy editors may be going the way of uniformed elevator operators abound. The Orange County Register, in California, is outsourcing some of its copy editing to India. The New York Times noted recently that Washington’s new shrine to journalism, the Newseum, is without an exhibit on copy editing and its role in American newspaper history.

Having foreseen some of this, and also to find a way to deal with what many copy editors see as discrimination against their cohort, McIntyre helped establish The American Copy Editors Society in 1997, a national group that gives voice to people who do this vital but unsung work. He has served as its president twice. He teaches copy editing at Loyola College in Maryland, even though few of his students express interest in print journalism. He gives workshops and writes about the danger inherent in the diminution of this valuable craft and the consequences – not only for newspapers, but for book publishers as well.

Obviously, McIntyre’s expectations for the future of newspapers are not bright and grand. Whose are? He is uncertain as to whether they will disappear entirely or evolve into some sort of shrunken paper product or electronic news medium. But if they do, “we will still need journalists to gather information. We will still need editors to shape it.”

Which is to say, the “life of kings” may endure here and there, in some form or another.

This should not be taken as a Panglossian prediction that all will come out well in the end: “Hundreds of journalists’ jobs are being eliminated throughout the country, and nobody can say when we will touch bottom,” McIntyre says.

This story does not have a happy ending, nor the opposite, because this story has not reached its denouement. “I think about it a lot. It is the shakiest of situations,” says the king of the copy desk, who then reveals some shakiness of his own, having just borrowed on the very day of this interview a staggering amount of money for his son’s university education.

And what will the boy do? He wants to be – a journalist? A food writer.