Players gather in the Santa Cruz Mountains to make music from saws

Loading...

| Felton, Calif.

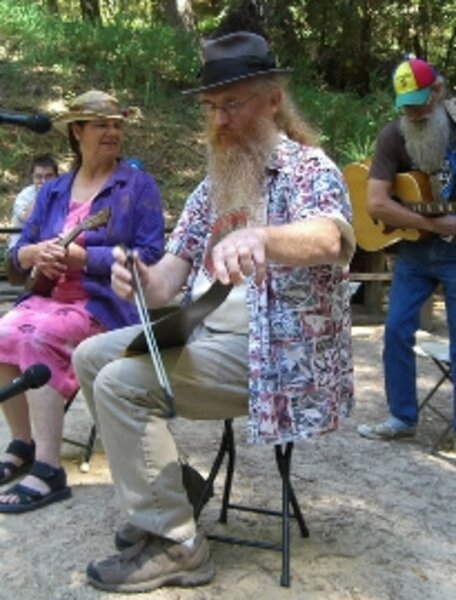

As the evening light dies over a dusty parking lot in the Santa Cruz Mountains, a small group of musicians pick up their bows. They balance their saws between their knees, bend back the sharp, toothy blades, and produce a sound at once Halloween eerie and songbird sweet.

The 30th annual Saw Players Picnic & Music Festival – held each summer in this small northern California community – officially takes place on the second Sunday in August. But tradition has it that sawyers begin jamming the day before. They play their tools-cum-instruments in the parking lot until 1 or 2 a.m., then toss and turn for a couple of hours in the back seats of their cars.

The saw players, like their instruments, are an admittedly shy and quirky bunch. There’s a social worker from Minneapolis, a traveling vaudeville performer from the Czech Republic, a community college instructor from Seattle – all drawn together by their shared desire to extract a haunting whistle from a carpenter’s tool.

During much of the year, they practice the melancholy music alone in their basements, or play backup to the saw’s often louder, more popular brethren: the fiddle, the banjo, the guitar.

So, for the handful who have gathered for this pre-festival jam session, the night is a rare opportunity to trade tips, unite melodies, and bask in a shared adoration of the oft-overshadowed musical saw.

“More saw! More saw!” cries Morgan Cowin, the tall, white-haired president of the International Musical Saw Association, during one tune in which the instruments are being drowned out by a rowdy guitarist.

“More saw!” another player echoes.

The evening feels both awkward and affectionate, like a reunion of distant relatives. But there is a strange wonder to it, too, this group of musicians playing John Lennon and the Indigo Girls a few yards away from a green plastic Port-A-Potty. Beauty can emerge at the most improbable times and places, after all. The saw is a ready reminder of that.

•••

Sawyers like to say their instrument is easy to learn, but difficult to master. Players grip the saw’s handle between their legs, teeth pointing toward them. They produce notes by gliding a violin bow across the flat side while bending the blade into an S curve. Though beginners can often coax out only a squeaky warble, in the hands of the best, the saw sounds like a melancholy flute.

Most players say they were immediately struck by the saw’s peculiar sound – which Mr. Cowin believes was discovered by factory workers and carpenters in the 1700s or 1800s, before being widely popularized during the 1920s and ’30s in vaudeville.

“I was like, ‘You can play a song on this thing?’ ” says Jodi Golden-White, the community college instructor from Seattle.

Others came to it more gradually, after being put off by the instrument’s inherent weirdness. “I was like, ‘Oh my goodness, this is really strange,’ ” says Steve Cook, the social worker from Minneapolis. He’d shunned most of his father’s attempts to teach him the instrument, then picked it up after his father’s death.

Musicians here recognize the saw’s weirdness as much as anyone. References to ripped pants abound, and puns about “C-saws” and “sharp students” are plentiful. Although saw players tend to be shier than their guitar-playing counterparts, they can’t help but enjoy the impressed murmurs: You can make music out of that?

“Everybody and their brother plays guitar,” says Cowin. “Nobody plays the saw. If you’re a saw player, you’re immediately a star.”

As starlight punctuates the night sky on a Saturday, players gather in a small circle around a half dozen flickering tea lights. The mood is relaxed and cheerful.

Most old-timers, like Cowin, feel optimistic that the saw’s popularity will continue, even though one of the instrument’s greatest advocates, Charlie Blacklock, the founder of the Musical Saw Association, passed away this year. They cite the success of virtuosos such as David Weiss, whose playing is featured in the soundtracks of the 2000 film “O Brother, Where Art Thou?” and, more recently, in “Pirates of the Caribbean: At World’s End.” Mr. Weiss, who spent three decades as principal oboist for the Los Angeles Philharmonic, plays a Stanley “handyman.”

Many new players, like Mariah Stricker, say the saw makes them feel like musicians for the first time in their lives. Ms. Stricker, who works in the plant-science department of the University of California, Davis, hadn’t played an instrument since middle school. Now she practices between two and five hours a day.

“The thing is, when the electricity finally goes out once and for all, saw is what everybody is going to be listening to,” quips Thomas Spearance, a sawyer from Fort Bragg, Calif.

Cowin has been flown to Japan and China to play the saw. Originally trained as a classical guitarist, he heard his first saw music while walking the streets of Copenhagen in 1968. Three years later, he bought his first kit (saw, violin bow, lessons, and case) for $39. He liked the saw’s simplicity and durability. What other instrument, he muses, can be used to stir a fire?

•••

On Sunday morning, after a late night of jamming, the sawyers rub sleep from their eyes, and traipse over a covered bridge onto the grounds of Roaring Camp Railroads. The camp is an assortment of old wood buildings, picnic tables, and steam trains designed to take visitors back to the 1880s. A group of mountain men is rendezvousing there for the weekend.

Blacklock’s relatives, who now run the Charlie Blacklock Musical Saws company, have set up a table to sell custom-made saws in lengths from 26 to 36 inches. Blacklock’s grandson, Kenny, wears an orange festival T-shirt advertising “Cutting Edge Music.”

Although Cowin estimates tens of thousands of people play the saw worldwide, this year’s festival has drawn only two dozen or so. Late Sunday morning, audience members are treated to a “Saw Off” among six up-and-coming sawyers, a couple of whom suffer minor stage fright before performing. A young woman in flip-flops plays a multi-part rendition of “Hot Stuff.” A man with a red-and-white beard and feathered cap performs “Beautiful Brown Eyes.”

In the afternoon, Thomas Spearance climbs on stage and holds up his saw. The man who crafted this instrument, he tells the audience, has changed his life forever.

“This is Charlie’s festival,” Mr. Spearance says. “And Charlie is always going to be here.”

As he begins his haunting version of “Amazing Grace,” a gentle breeze lifts the unlikely music into the sky. Once he finishes, perhaps wishing to drive home the point, he stands up and balances his saw on his nose.

He gazes heavenward and shouts: “Make some music, children!”