Your message here? Ads come to the math quiz.

| San Diego

San Diego

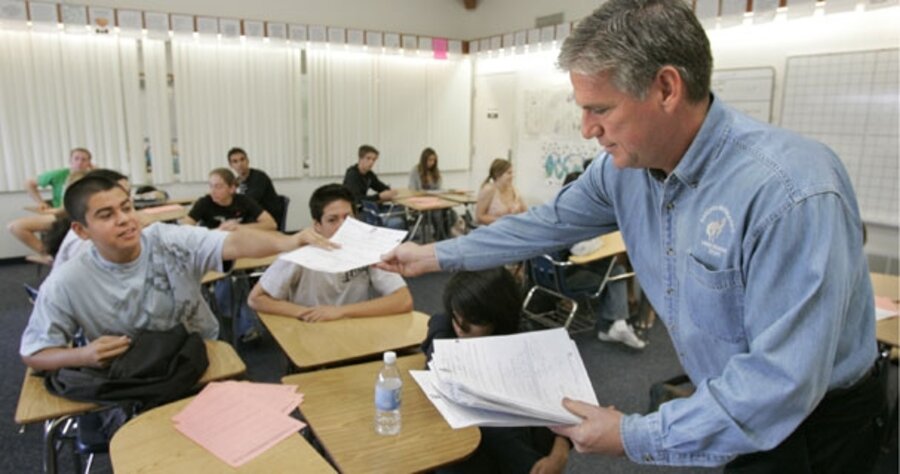

Tom Farber is the kind of guy with whom you wouldn’t mind sharing a hot tub conversation. Silver-haired, fit, and gregarious, he’s telling his tubmate at a condo complex that he is a teacher. Been in the profession 23 years, 17 at Rancho Bernardo High, in a tony suburb of San Diego. As he talks over the noise of jet-propelled bubbles, his story turns to the underfunding of California schools.

This is how Mr. Farber’s 15 minutes of fame – perhaps extended to half an hour – begins.

The chance conversation, with a neighbor who’s a magazine editor, turns to the way Farber is bridging a classroom budget deficit.

Realizing he couldn’t afford all the paper he needed for his calculus tests, he decided to get creative. On Back to School Night, he asked students’ parents if they would sponsor tests. That’s right, pay to put ads at the bottom of the first page.

He collected $270 that night – enough to meet the cost of producing quizzes, tests, and a semester final.

As the two men talk, the neighbor senses there’s a story here. It first appears in San Diego Magazine. The story is picked up by the local NBC-TV affiliate, and followed by an article in The San Diego Union-Tribune. USA Today then puts Farber on its front page. After that, a media maelstrom ensues.

His tale is told on national network news programs – ABC, CBS, Fox, CNN and AP send reporters and cameras to his classroom. Producers get in touch from The Bonnie Hunt Show and Dr. Phil. Canadian TV crews and Japanese newspapers send requests for his time.

Farber estimates he’s fielded more than three dozen such inquiries – and counting. He grants about a dozen interviews. He even takes a day off from school to “do media.”

From the mid-November day the story first appears through the second week of December, he says, he gets two or three calls a day from radio stations. He turns many down, but he does agree to do a program by a fellow educator in Nebraska: Teachers have to support teachers.

“The exposure this has gotten has gone beyond anything I would have believed,” says Farber. He feels stress from holding down two jobs, being a divorced dad to a 19-year-old daughter, and acting as a media figure. “I can’t let this be a distraction to taking care of my kids in the classroom. I’m happy to talk about the ads on the tests. But the message is underfunded schools. As a nation we have to focus on this. We can’t mortgage our future. And as it is, we’re setting kids up for major problems.”

•••

Along with the media requests, Farber gets messages from about 50 individuals and companies from around the country that want to buy ads. One line of text – the “ad” can be an inspirational quote or a plug for a company – costs $10 on a quiz, $20 on a test, or $30 on the semester final.

Even in the face of high demand, Farber keeps his pricing structure intact. He estimates he has more than $1,000 in pledges. Some advertisers – an orthodontist, an online retailer of prom dresses – really want to get their products in front of high school consumers.

Most also want to support a teacher who thinks outside the box. Travis King first sees Farber’s story in The San Diego Union-Tribune. The Marine staff sergeant owns a bargain-priced outdoor sports gear company called TNTRide.

He says his company tries to be community oriented, and believes Farber is of the same mind-set. King sends him an e-mail, and Farber replies with an ad request form.

“We live in Rancho Bernardo and my daughter is in this [Poway Unified] school district,” says Mr. King, a veteran who has served in Afghanistan and Iraq and now is battling a brain tumor. “My daughter is always talking about her school not having enough money.” King spends $30 to put TNTRide ads on a quiz and a test.

A number of teachers contact Farber to talk about enacting similar programs. Dana Schaed first sees Farber’s story on Yahoo.com. Assistant principal for student life at St. John Vianney High, a private school with 1,035 students in Holmdel, N.J., she says keeping tuition low is always a priority.

She corresponds with Farber, and aims to get board approval for ads on tests.

“We’ll probably keep pricing the same as [Farber’s],” says Mr. Schaed. “We like the inspirational messages approach. She is also contemplating offering product placements: Local companies could pay to have their name used in, say, a math word problem.

•••

Farber’s students are mostly unaffected by the ads, or the media attention. “Academically, it didn’t affect me,” says 16-year-old junior Alex Flood. “I wouldn’t like it if huge companies started doing this in public schools. I’m OK with local stores doing it.”

But the ads saddened 17-year-old senior Kristy Foss. “In an ideal situation, society – the state – would provide enough funds for schools.”

California school officials say the state’s allotment for education is at least $3 billion short. In this weak economy, cuts may be on the horizon that would make the gap worse. Faced with a budget crunch, many schools, like Rancho Bernardo, opted to keep teachers and trim programs. Poway Unified superintendent Don Phillips says the school district reduced the allocation for supplies by 30 percent – a drop from $272,000 to $190,000.

And that’s why a calculus teacher – who gives a test and a quiz for each of the seven chapters he teaches on things like applications of the derivative and advanced integration techniques – can’t pay for paper without hitting up parents and the public.

Sensitive to the advertorial encroachment on his tests, Farber polls his 165 students. All say the inspirational quotes are acceptable; 92 percent aren’t bothered by ads. On the next test, Farber will give students a choice – with or without the bottom-line mentions? Ten percent say they will opt for the ones without ads.

Farber warily believes his practice could evolve into a profit center for schools. “If it’s done on a small scale, I recommend focusing on the quotes,” he says. “If this were to be done on a bigger scale, schools or districts would have to be more proactive.”

To anyone who disagrees with ads on test, Farber responds: “I tell them to complain to their local politicians that schools need to be better funded. Or I tell them to make a donation to their local school.”

Above all else, Farber treasures the notion that his actions have allowed for the proverbial “teachable moment.”

“I tell my students to see what one person can do,” he says. “I solved a problem, and I’m getting a message out. This got bigger than I could have imagined. But my students are seeing that one person does have a voice. Don’t ever think your voice – or your vote – doesn’t count. It does, and it can.”

Even if you’re just chatting with your neighbor in your hot tub.