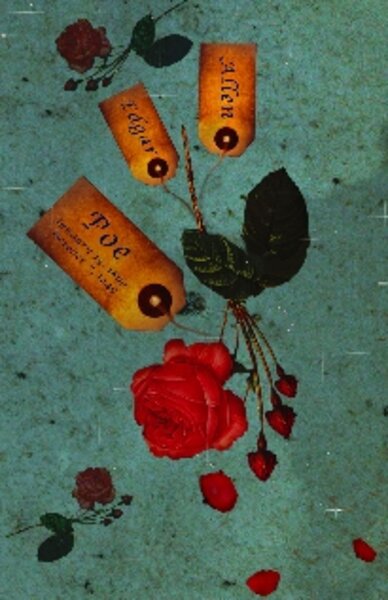

A telltale Poe-pourri

Loading...

Baltimore

He is Baltimore’s sad-eyed genius. He doesn’t want for admirers, and hasn’t for the 160 years since he was found, Oct. 3, 1849, in a tavern, dressed in rags, haggard, incoherent; he was four days away from the end of his life, at age 40. The tavern was not far from where he rests today, in a bricky urban cemetery, softened by birch trees and maples, black-barked and leafless, where a path winds among tombstones bearing the names of generals who fought the English wars, politicians, high-born merchants, but of only one poet.

Every Jan. 19, his enamored constituents assemble late at night at the Westminster Hall and Burying Ground. Hundreds stand bunched and bundled against the cold, till dawn, if necessary. They await a man in a black cloak, broad-brimmed hat, and a scarf that conceals his face. He arrives suddenly, deposits a half bottle of French cognac and three roses at the poet’s tomb, then disappears. He is known as the Poe Toaster and has earned a place in the popular legacy of Edgar Allan Poe. He personifies a small mystery in a Gothic city that loves them, and idiosyncrasies of other sorts as well. (Think John Waters.) I recall, long ago, an old newspaper man telling me of a Baltimore mayor – whose name he refused to surrender – who placed flowers on the grave of John Wilkes Booth. “Booth at least was among the higher order of assassins,” he allegedly said. “We must make the most of the few illustrious dead we have.”

The story smells of Confederate dust, and is probably apocryphal. But it reinforces the conviction, held by some, that Baltimore lives a quarter turn behind nearly everywhere else; it is a guarder of secrets, of which it has many.

This January will mark not only the 60th anniversary of the Poe Taster’s ceremony, but, of greater significance, the bicentennial of Edgar Allan Poe’s birth. Barring a blizzard, the cemetery entrance will swarm with grave watchers.

Over the years, relatively few have disturbed the Poe Toaster at his work: None have penetrated his disguise, though it is known that the one who arrives this Jan. 19 will not be the original. Jeffrey A. Savoye, president of the Edgar Allan Poe Society of Baltimore, and Jeff Jerome, curator of the Poe House, have been informed through an anonymous letter from the originator that “the torch has been passed” to his two sons.

So why has no one succeeded in unmasking the man? Maybe it’s for want of trying hard enough. Maybe Baltimoreans embrace the mystery so much they prefer it to its resolution.

“Nobody I ever met in Baltimore talked about unveiling the Poe Toaster,” says Laura Lippman, the resident mystery writer, author of the Tess Monaghan stories. “That would be like undermining the mystery of Santa Claus.”

She feels the same toward an even darker Poe mystery: How did Poe get into that lethal state of disintegration and disorientation that ended his life and career?

“I think we’ll never know why he died that way,” says Ms. Lippman. “It’s a mystery, and properly so,” she says, and asks, with faint outrage, “Why are people so interested in solving this?”

Lippman favors the prevailing theory: that on election day, Oct. 3, 1849, or on the day before, Poe was seized by political thugs, drugged, sated with whiskey, confined – probably in a dank basement – then dragged out and forced to vote at numerous polling places. His captors then dumped him in the gutter. Found later by an old friend and taken to a hospital, Poe never became coherent before he died.

The practice was called “cooping,” common in those days of riotous American politics. Every party and splinter group had its own cohort of thugs, charged with getting out the vote any way they could. They were lethal gangs and bore names like the “Rip Raps” or “Plug Uglies,” the latter being the street muscle of the American Party or Know Nothings, prominent during the pre-Civil War years.

“I think no one has successfully shot that theory down,” says Lippman. “I’m OK with it.”

So are most, though there are many competing gruesome theories.

• • •

The cemetery where Edgar Allan Poe lies is not in one of Baltimore’s posh neighborhoods. Yet it displays none of the reckless blight of vandals. And no graffiti. Lu Ann Marshall, chief tour guide at the Westminster Burial Ground, suggests why. “Some people believe the place is haunted,” says this woman filled with knowledge of the dark poet, the greatest literary critic of his times, the genius who gave birth to the modern detective yarn with stories like “The Purloined Letter” and “The Murders in the Rue Morgue.”

Poe is in this green place because his grandfather, David Poe, Sr., owned a lot in the cemetery, where Poe’s grandparents and older brother were already buried. Poe lies here, by his wife, who was also his cousin, the frail Virginia, and his mother-in-law and aunt, Maria Clemm. People leave pennies on Poe’s monument; they add up to about $60 a year, a small contribution to its maintenance. Ms. Marshall estimates that about 2,000 people visit the Poe monument annually.

In a far bleaker neighborhood close by, stands the house Poe shared with his Virginia, Maria, and briefly Poe’s grandmother and another cousin. In one way his three years in this “doll’s house” dwelling on Amity Street (1832 to 1835) were probably among the happier ones of his turbulent life, despite the physical circumstances they endured there.

“He was starving; they were all starving,” says Mr. Jerome, the curator. “But here he wrote a masterpiece, “Berenice,” his first true horror story. It changed the direction of his life.”

Jerome is not only the caretaker of this musty 1830s house, with its memorabilia, daguerreotypes in shadowed rooms, and other morose images of Poe: He is a known authority on the man and his work.

“Berenice” was a story so horrific that it outraged people, especially, no doubt, those who had issues with their teeth. It even scared Poe himself, made him fearful for his reputation. “But it made him realize that people, though horrified, still liked to read it,” Jerome says. “If Poe didn’t write ‘Berenice,’ he would not have turned to horror.”

It became the genre most associated with him today.

Reference to this artistic pivot by Poe was sufficient for curator Jerome to fend off claims by other cities to Poe’s legacy, especially the one heard from Philadelphia recently for his very remains, this because so much of his work was inspired by the City of Brotherly Love.

“The idea of moving the body just angered me,” says Jerome. “Here in Baltimore, Poe was shown the light.” Or darkness, depending on how one interprets the metaphor. Think of “The Fall of the House of Usher,” or “The Black Cat.” Hideous, but saleable.

Abundant festivities are planned to honor Poe throughout 2009. Lectures, seminars, poetic recitations, and films, not only in Baltimore, but in Richmond, Va., Philadelphia, even Boston where he was born in 1809 to a pair of itinerant actors, both of whom died before their son reached age 3. Boston he loved least among the cities closest to his telltale heart, though itw was there that he published his first book, “Tamerlane and Other Poems.” According to Mr. Savoye, Poe thought Boston “had its nose up in the air.”

“He disliked the Transcendentalists, [especially Ralph Waldo Emerson.] They thought man was making progress.” Their optimism offended him.

Baltimore’s “ ‘Poe-pourri’ of exciting events” will highlight recitations by the actor John Astin, of “Addams Family” fame.

Jerome is even arranging a “public funeral,” not granted the famous man in 1849, when only six people stood by as Poe was quickly put into the ground. Jerome expects VIPs to come this time to eulogize America’s great poet. He has invited many who shared Gothic perceptions similar to those nourished by Poe. People like Alfred Hitchcock, H.G. Wells, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, among others.

Such impossible expectations are, well, so Baltimore.