Artists put contemporary twist on Norman Rockwell’s ‘freedoms’

Loading...

| Stockbridge, Mass.

Norman Rockwell’s now iconic paintings from the 1940s are being reimagined by artists aiming to show their relevance to public discourse today. The originals were inspired by a 1941 speech by President Franklin D. Roosevelt. They represent “Freedom of Speech,” “Freedom of Worship,” “Freedom from Want,” and “Freedom from Fear.” Originally published in The Saturday Evening Post, they were later used to promote the purchase of war bonds during World War II. While some of the new works touch on hot-button issues such as police brutality or deportation, more broadly they represent an intersection of art and civic engagement that challenges the binary national dialogue. Whatever their political views, people can often unite around basic human desires to worship and speak freely, to be free from fear and want. Gina Belafonte, co-director of an arts and social justice initiative founded by her father, Harry, helped recruit people to pose in some of the new photographs. To her, they show that even with greater diversity in the United States, “we can get along, and we can be respectful, and we can make space and time for each other in our hearts and in our minds.”

Why We Wrote This

Rockwell's paintings represent freedoms most Americans agree on. What happens to the discussion when the World War II-era images are updated for a modern audience?

On Thanksgiving weekend, 75 years after Norman Rockwell took brush to canvas to create his famous Four Freedoms paintings, they sprang to life again – in song.

With dissonance and syncopated rhythms embodying the diverging voices of democracy, a chorus at the Norman Rockwell Museum here sang a verse from “Freedom of Speech”: “You know that We the People agree to disagree/ and that’s Okay, we like it that way!/ A little bit of chaos creates the space for a healthy democracy…”

Inspired by a 1941 speech by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, the paintings – which also include “Freedom of Worship,” “Freedom from Want,” and “Freedom from Fear” – were originally published in The Saturday Evening Post and then used to promote the purchase of war bonds during World War II.

Why We Wrote This

Rockwell's paintings represent freedoms most Americans agree on. What happens to the discussion when the World War II-era images are updated for a modern audience?

Lately, many artists have been putting their contemporary twist on Rockwell’s iconic aspirational portraits – and reaching a wide audience through political billboards, re-posed modern photographs, sign-making events, and even a ballet performance.

While some of the new works touch on hot-button issues such as police brutality or deportation, more broadly they represent an intersection of art and civic engagement that challenges the binary national dialogue. Whatever their political views, people can often unite around basic human desires to worship and speak freely, to be free from fear and want.

“The paintings seem so dynamic and relevant,” says John Myers, the composer who began creating the Four Freedoms songs in 2015. His compositions are not “overtly political,” but in the wake of the 2016 election, “I felt that [these freedoms] were now under threat, and somehow that also made them more precious,” says Dr. Myers, a professor of music and cultural studies at Bard College at Simon’s Rock in nearby Great Barrington, Mass.

Complicated issues (think health care or immigration) are often oversimplified into partisan camps on 24-hour cable news and social media, but artists can play a role in prompting more nuanced conversations through “radically creative thinking,” says artist Eric Gottesman. Along with Hank Willis Thomas, he co-founded For Freedoms as an artist-run network to encourage public discourse through art.

The goal is to have “creativity [be] seen as an essential patriotic American value,” he says.

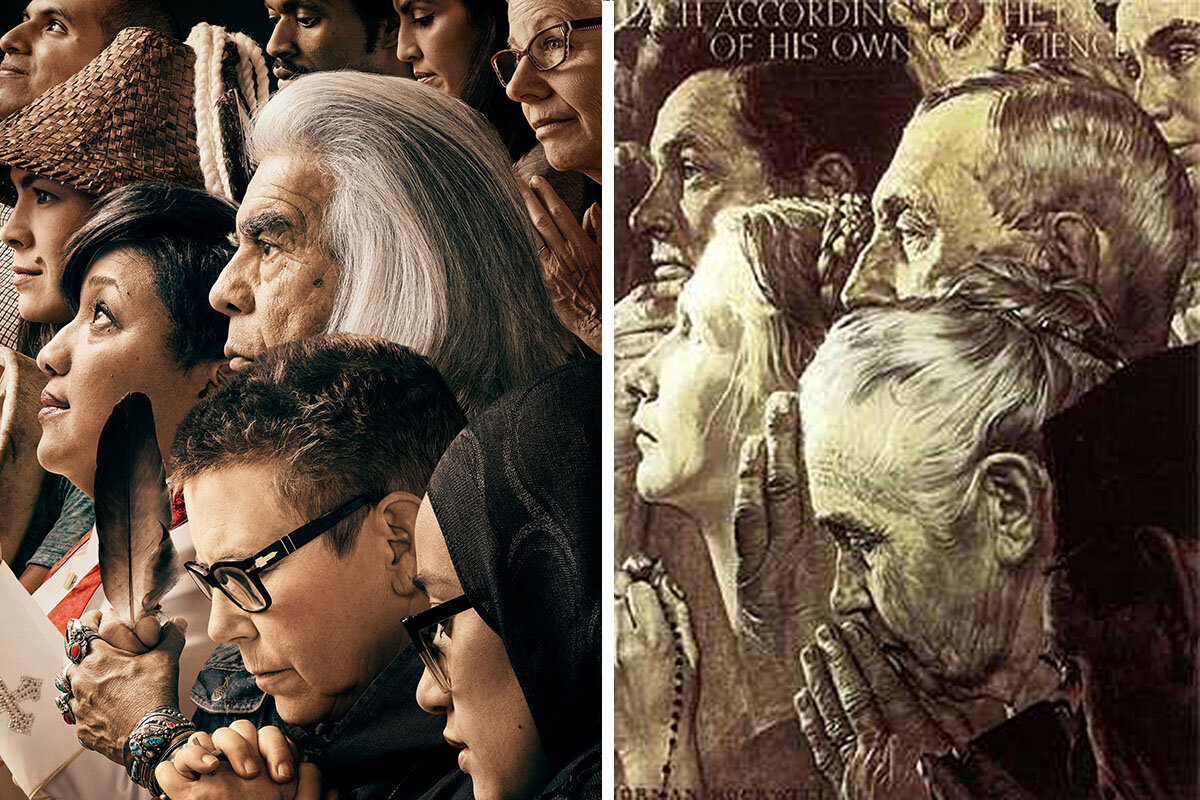

Earlier this year, Mr. Thomas and Emily Shur collaborated with For Freedoms to produce a series of photographs – mirroring Rockwell’s compositions by posing celebrities, activists, religious leaders, and everyday people. The images clearly signal we’re not in the 1940s anymore, yet they bear the same timeless expressions of hope, reverence, concern, joy.

The new “Freedom of Worship” photographs, for instance, include a woman wearing hijab, a Native American man holding a feather, and a man wearing a turban.

They show that even with greater diversity in the United States, “we can get along, and we can be respectful, and we can make space and time for each other in our hearts and in our minds,” says Gina Belafonte, co-director of Sankofa.org, an arts and social justice initiative founded by her father, Harry Belafonte. She helped recruit and coordinate people to pose in the photographs.

The musical composition based on “Freedom to Worship” was “the hardest one,” says Myers (his project was supported by the Norman Rockwell Museum and is not affiliated with For Freedoms). Myers included Middle Eastern scales and a lyric mentioning the Quran, to include Islam alongside Christian and Judaic references and Renaissance techniques.

At the November concert, a little girl waved her arms like conductor Christine Gevert as the Crescendo Vocal Ensemble sang “My faith means more to me than life itself./ And yet we must respect the heritage and decisions of our neighbors.”

“It’s very exciting to see that artists of all kinds really still identify the Four Freedoms and particularly Rockwell’s work as being relevant today,” says Stephanie Plunkett, the museum’s chief curator.

The Rockwell paintings are traveling in the US and France until September 2020 as part of the museum’s exhibit “Enduring Ideals: Rockwell, Roosevelt & the Four Freedoms.” The exhibit includes 40 contemporary works selected from among 1,000 entries. They run the gamut – from a painting of a homeless woman and child in the doorway of a fancy bakery to a piece combining drawing and digital media as a comment on “fake news.”

It also includes context from Rockwell’s later works on subjects like racial integration. Many “have thought of him as an artist who painted hometown scenes, scenes of everyday life, often with a touch of humor. To see him take on some very important social concerns in a strong way is very surprising to people,” Ms. Plunkett says.

This year, For Freedoms partnered with hundreds of galleries and colleges on a 50 State Initiative, mounting billboards and hosting civic events in advance of midterm elections.

One black-and-white billboard displayed the Arabic words for “human being.” Created by artist Jamila El Sahili, it towered over voters in Michigan, one of two states that went on to elect the first Muslim women to the US Congress.

The Vermont College of Fine Arts in Montpelier hosted a For Freedoms sign-making event, inviting people to fill in templates with words that showed appreciation for, or concerns about, their freedoms. Some sign-makers marched in the Fourth of July parade.

“If you start a conversation about the things you appreciate about being an American, you can get a lot of people to weigh in on that who have varying political opinions,” says Brittany Powell, associate director of a graphic design program at the college.

The For Freedoms projects are “expanding the civic vocabulary of viewers of art,” Mr. Gottesman says. Analysis of a large survey to measure the impact is pending.

As politicians around the world focus on a variety of perceived threats, Gottesman says he and his For Freedoms partners hope it’s possible "to motivate people without stoking their fears. Artists often do that by creating alternative structures, alternative language to engage.”