Baseball was honoring great Black players. Then it lost the greatest of them all.

Loading...

| Birmingham, Ala.

There was no question about who would be the star of the show as Major League Baseball descended upon Alabama for a weeklong series of Negro League tributes. But just to make sure, Birmingham native Willie Mays’ name was on the marquee of the historic Carver Theater ahead of a documentary screening Monday night.

And then, as Tuesday’s minor league game went into the good night, so did the “Say Hey Kid.”

Why We Wrote This

This week, baseball is celebrating the Negro Leagues legacy in Birmingham, Alabama. The death of hometown hero Willie Mays has underlined his own incomparable legacy and how his life intertwined with Birmingham, baseball, and Black America.

“It’s very untimely,” offers comedian and actor Roy Wood Jr., a fellow son of Birmingham who was reporting at Rickwood Field at the time Mr. Mays’ passing at age 93 was announced.

“But to have seen and been in a baseball stadium when the announcement came out, you saw exactly what he did as a player,” says Mr. Wood, whose new podcast is called “Road to Rickwood.” “He brought people together, regardless of race or lifestyle. Strangers in this crowd here were hugging.”

There was no question about who would be the star of the show as Major League Baseball descended upon Alabama for a weeklong series of Negro League tributes. But just to make sure, Birmingham native Willie Mays’ name was on the marquee of the historic Carver Theater ahead of a documentary screening Monday night.

From documentaries to baseball games, his presence was looming. And then, as Tuesday’s minor league game went into the good night, so did the “Say Hey Kid.”

“It’s very untimely,” offers comedian and actor Roy Wood Jr., a fellow son of Birmingham who was reporting at Rickwood Field at the time Mr. Mays’ passing at age 93 was announced.

Why We Wrote This

This week, baseball is celebrating the Negro Leagues legacy in Birmingham, Alabama. The death of hometown hero Willie Mays has underlined his own incomparable legacy and how his life intertwined with Birmingham, baseball, and Black America.

“But to have seen and been in a baseball stadium when the announcement came out, you saw exactly what he did as a player,” says Mr. Wood, whose new podcast is called “Road to Rickwood.” “He brought people together, regardless of race or lifestyle. Strangers in this crowd here were hugging.”

He offered those heartfelt sentiments during a celebrity game at the famed park on Wednesday evening, with a tribute game between the St. Louis Cardinals and San Francisco Giants slated to take place Thursday. Within a baseball throw of Mr. Wood, a comedian who came to fame through his performance at the White House Correspondents’ dinner in 2023 and his tenure with “The Daily Show,” was Mr. Mays’ Hall of Fame plaque from Cooperstown.

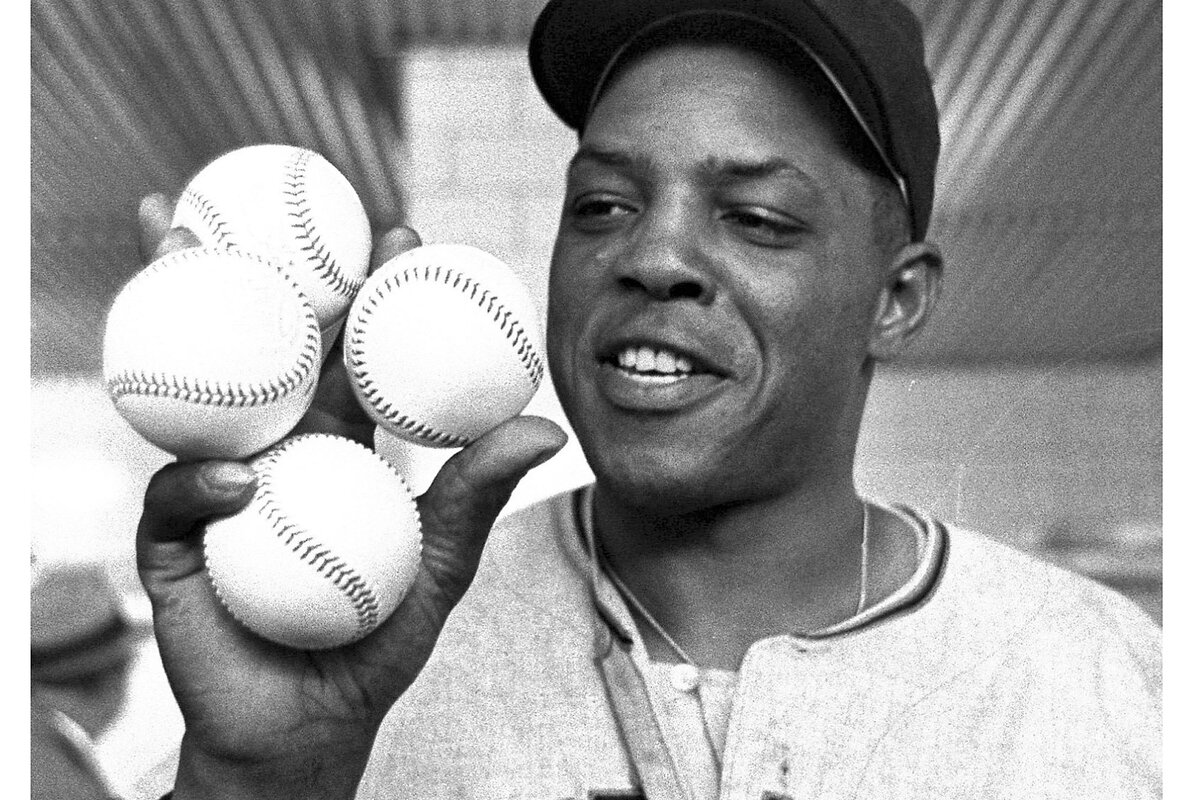

The gold-plated memorial paled in comparison with Mr. Mays’ sterling career, even as the late afternoon sun beamed off it. Mr. Mays, a 24-time All-Star and 12-time Gold Glove winner, is considered by many the greatest player in MLB history. During a week in which MLB confirmed its commitment to giving the Negro Leagues their flowers, it was the city of Birmingham that blossomed to life, whether it was through various murals of Mr. Mays or the stories of his legend.

Rickwood Field, the oldest ballpark in the United States, took on additional significance this week in the aftermath of the death of Mr. Mays. He began his baseball career there in 1948 in the Negro Leagues as a 17-year-old. He played for the Birmingham Black Barons, and there’s a picture in the recesses of one of the park’s gift shops with members of that team. Just one person in that picture is still with us – the Rev. William Greason, one of Mr. Mays’ former teammates. He’s slated to throw out the first pitch at Thursday evening’s MLB game.

“There has never been a ballplayer as good as Willie Mays,” Mr. Greason told The Washington Post.

On Monday, Mr. Mays’ passing was the furthest thing from Birmingham’s mind, as the HBO documentary with his name played at Carver. After the screening, director Nelson George and Mr. Mays’ son, Michael, were on hand for a brief dialogue.

Michael Mays, who is from Harlem, talked about the love and appreciation his family has for Birmingham.

“It’s kind of emotional because it’s full circle,” the younger Mays told the audience, almost prophetically. “It’s been an honor to meet [the surviving Negro Leaguers] and get to talk to them. We all know their hardship, we all know their struggle, but they marched through it like it wasn’t nothing.

“The joy and the happiness that went on in the community, despite the struggle, I can sense that when I come here,” he added. “That’s the core of my dad’s character. It’s a Birmingham thing. It’s a Fairfield thing. It’s a family thing.”

“Say Hey” wasn’t just an audible and welcoming gesture from Mr. Mays. It constituted how he played the game.

That flair also had a tinge of defiance, which may have been interpreted as a type of protest during the segregationist and racist period during which Mr. Mays played, explains Anthony Williams, director of the Negro Southern League Museum in Birmingham.

“There’s a certain stylishness that just comes with [Black] culture. There’s a certain way of doing things differently from the regimented way,” says Mr. Williams. “You still have to learn discipline, the rules, and structure, but at the same time, you don’t have to adhere to it. You can actually have an edge by personalizing your own style within the rules. I think that’s what we see when we think of a Willie Mays or a Satchel Paige.”

Mr. Williams’ words open up an interesting dichotomy, considering one section of the Mays documentary, which talks about a brief spat with Jackie Robinson.

Mr. Robinson believed that Mr. Mays didn’t do enough to speak up about the Civil Rights Movement, which was ironic considering a similar ideological conflict between Mr. Robinson and Malcolm X. Mr. Mays acknowledged Mr. Robinson’s efforts toward civil rights, and then offered, “So too, have I, but in a different way.”

The documentary goes on to say that Mr. Mays mentored a host of Black baseball players, including Bobby Bonds, who later named Mr. Mays the godfather to his son, Barry.

Mr. Mays’ celebrity and approach to the game inspired the generations that would follow. Even as the number of Black baseball players continues to dwindle, there are advocates for the game such as former New York Yankees pitcher CC Sabathia, who appreciated the Negro League tributes at Rickwood.

“In the wake of Willie’s passing, this feels right,” Mr. Sabathia says. “I take on the personal responsibility of bringing more Black baseball players, but we need more Black families at the games. We need more accessible experiences like this that bring more fans, which will bring more Black players.”

That type of intentionality fits the week to a T. The hope is that it will be easy for prospective fans and baseball enthusiasts alike to “say hey.” As accolades and tributes continue to pour in, one thing is for certain – saying goodbye is a much more difficult task.