Sculpture: Sending in angels

| New York

The artist Lin Evola-Smidt lives these days in Manhattan, but she is fond of saying that her sculpting career really began 3,000 miles and a world away. This was back in the early 1990s, when Los Angeles murder rates were among the highest in the country and local authorities struggled to tamp down illegal gun sales. Ms. Evola-Smidt followed the news from her San Francisco home with a growing sense of dread. Her son, Jason, was 8 at the time. What kind of world did he stand to inherit?

"I'd been an artist since the first time I opened my eyes, but I wanted more at that moment than to just create a piece of art. I wanted people to make a shift within themselves," Evola-Smidt remembers. She is speaking at the offices of her publicity firm, Rubenstein Communications, which sits some 30 floors above midtown Manhattan. It's almost winter, and behind her, outside a row of ceiling-length glass windows, the greenery of Central Park is turning slowly to dun.

With the benefit of hindsight, of course, the whole, grand idea sounds pretty outlandish, even to Evola-Smidt: First, convince a chunk of Los Angeles residents to voluntarily give up their guns. Then melt down the weapons and create art. And not just any art, but statues of angels, which, as Evola-Smidt points out, have historically stood for "the uplifting of humanity." For a few weeks, Evola-Smidt played devil's advocate with herself. "I told myself to get ready," she says. "I thought lots of people would say 'No way.'"

But with the aid of the Los Angeles County Sheriff's Department, Evola-Smidt's program slowly took shape, and by the end of the '90s, she had created a small army of metal angels, each standing between one and three feet tall. She attracted press attention, although not without a few hitches – when CNN arrived to film the first weapons melt, the smoke from the guns was so acrid that the network's cameras failed.

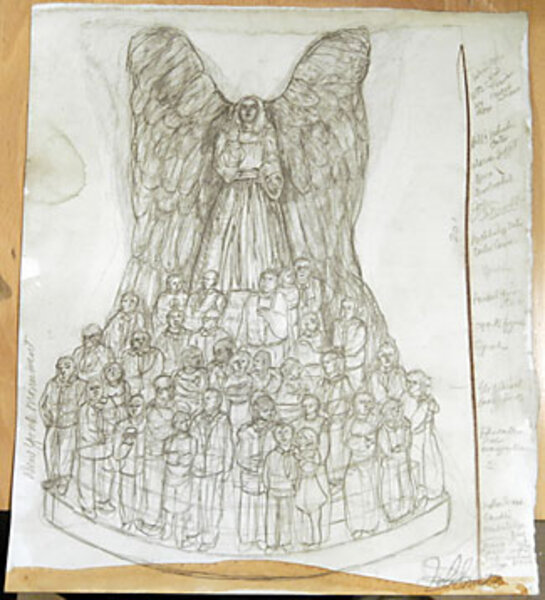

She spoke to big-name politicians from around the globe, including former President Bill Clinton, who was the first recipient of a Peace Angel. And she shuttled between coasts and continents, drumming up interest in disarmament. All the while, Evola-Smidt was working off the early designs she'd first conceived in California: a sculpture with traces of both Renaissance and modern influence, familiar in form and unique in metallurgic makeup. The angels have been described as soothing and "serene," although it's the wings that really draw the eye – wide and towering and rumpled by an imaginary wind.

"She was always very passionate about making the angels, both from an arts and cultural standpoint," says Chris McGrath, a manager at Polich Tallix Fine Art Foundry. Polich, which is located in Rock Tavern, N.Y., has been involved with the Peace Angel project since 1999; each sculpture is now produced there under Evola-Smidt's guidance.

About 12 years ago, after the project had gathered a good deal of steam, Evola-Smidt decided to ratchet up the scale of the angels. If the old sculptures could fit comfortably on a tabletop, the new ones would be fit for a park – Evola-Smidt envisioned some reaching 20 or 30 feet. The production time, of course, would increase exponentially; the implementation process was already extremely time intensive, requiring months of effort for each sculpture. So Evola-Smidt took it slowly, and in 1997 she finished work on a 13-foot "Renaissance Peace Angel."

In 2001, Evola-Smidt married a well-respected philanthropist named Daniel Peabody-Smidt, and after years of West Coast life, she relocated to New Jersey, where Mr. Peabody-Smidt lived. Things were very good; then they got very bad. On Sept. 11, terrorists crashed planes into the World Trade Center, and the newlyweds moved into lower Manhattan to lend support to the cleanup efforts. The "Renaissance Peace Angel," meanwhile, was transported to ground zero, to serve as a "symbol of hope," Evola-Smidt says.

But Evola-Smidt speculates that she and her husband stayed too long in the area without adequate protection in the face of poor air quality. Both eventually went through detox programs at local medical centers; still, Peabody-Smidt, who may have also been exposed to Agent Orange during his service in the Vietnam War, saw his health decline. In 2005, after a series of breakdowns, he took his own life.

"They say that grief makes you deeper," Evola-Smidt says, "Not for me. I didn't want to do anything for a long time." But when she emerged from her period of mourning, she says, she was more intent than ever to pour her energy into the Peace Angels project, which she began to think of as a kind of elegy for her late husband.

In September, exactly seven years after the 9/11 attacks, Evola-Smidt held a reception and dinner at the United Nations to announce the creation of the Art of Peace Charitable Trust, which, according to a pamphlet distributed at the event, will seek to combat "the proliferation of small firearms, light artillery and other weapons of war." A score of cities have reportedly expressed interest in the trust, including Jerusalem; Sarajevo, Bosnia-Herzegovina; and Johannesburg, South Africa.

But first, the hard part: wrangling the raw materials for the angels, which she says will include everything from melted small arms to decommissioned missile casings.

"Weapon-destruction programs are not often publicized by the governments that fund them," says Mark Marge, the UN liaison at International Action Network on Small Arms, which has been working to help Evola-Smidt secure weapons. "I think what makes Lin's project more powerful than a regular gun-removal program is the symbolism involved."

Evola-Smidt says wants the angels to go to areas where a peace process is already under way. "I think of each spot as an acupuncture point on the globe," she says.

The first angel built under the auspices of the trust will measure 30 feet high and is scheduled to be installed here in New York within the next four years. "To me," Evola-Smidt says of the sculpture, "it will be my husband in there. It's extremely personal. The project was personal before, but now there's no space in between."