Who owns an artist's legacy?

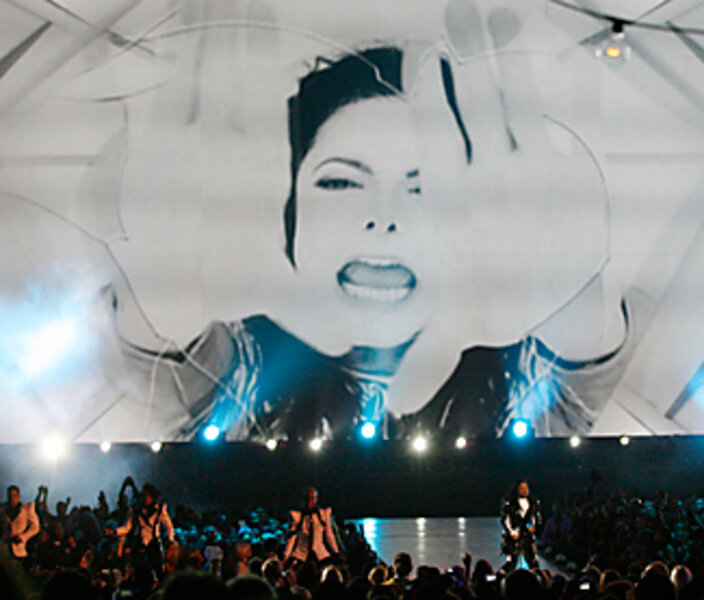

Living in an age of infinite media channels, death is no longer the career ender it once was. The megawattage that Michael Jackson generated in his halcyon days, for instance, is not expected to wane. With hundreds of millions of dollars at stake, his songs and performances, and even eccentricities, are expected to be the gifts that keep on giving for whatever party ends up with the keys to his estate.

This doesn't make Jackson any different from other marquee entertainers whose deaths have done little to prevent new products bearing their likeness and body of work from saturating the marketplace each buying season. But what is different in Jackson's case is that, unlike the deaths of pop-culture icons Elvis Presley, Frank Sinatra, or Tupac Shakur, advances in digital media threaten to unbridle the ironclad control that gatekeepers use to guard their ownership rights, tailor a narrative, and protect a legacy.

Today, user-generated videos and music files and the distribution networks that allow them to flourish are positioned to tamper with the way Jackson – and any other public figure – is perceived far into the future. Recent technology not only allows users to easily create and distribute unauthorized tributes, which may be in good faith, it also allows the potential for biographical errors, public mockery, and the abuse of official works, all to float on Internet platforms indefinitely.

The result is an open-ended historical record ripe for purging, which, for public figures whose public life existed in images and sound, does not bode well for keeping the record straight. The Michael Jackson we know today may not be the Michael Jackson future generations may know, and there is little that estate holders can do about it.

There may be no other choice. Ico Bukvic, who studies the intersection of art and technology at Virginia Tech, says we are entering a new era where digital media is forcing us to appreciate art differently, including those who make it.

Artists, including filmmakers and songwriters, are always trying to remake the historical record by releasing, decades later, what they say is the official version of a cherished product. This includes Paul McCartney's reconfigured version of "Let It Be," the Beatles album he restored in 2003 to eliminate the choices made by original producer Phil Spector in 1970. Then there are recordings that never took place, such as a 2006 Ray Charles album featuring the Count Basie Orchestra – the orchestra parts were newly recorded, the vocals by Charles were lifted from a 1973 live performance. The result? A "concert" that never happened.

Often, the audience is not even aware of such studio concoctions, and if they are, the creations may be appreciated for their novelty value, like a recent remix album of Johnny Cash songs, which are turned into dance mixes, one a "duet" with Snoop Dogg. In fact, technology may be grooming an audience that may not be aware, or even care, if their favorite artist is gone, because they know they will always be around in some fashion.

That includes providing material for the audience to become involved in the manipulation themselves. Mash- ups, digital collages resulting in new work, are usually unauthorized creations by adventuresome knob-twisters. Officially, their works may be denounced, but there is no doubting their influence. When underground producer Danger Mouse remixed the Beatles with rapper Jay-Z in 2004, he created an unauthorized Internet hit. Two years later the surviving Beatles released their own mash-up of their catalog as a soundtrack to a Cirque du Soleil show, suggesting that the only way to fight abuse is to do a little tweaking yourself.

While unregulated activities will "undoubtedly shed enough light on the original product," it will also be valued in the same way as the source material, and one day may even surpass it in recognition. Says Mr. Bukvic, the trend is a result of "the audience not wanting to be the audience anymore, but participants who can shape their experience."

This new reality is unsettling those in charge of protecting the way deceased artists are appreciated.

"They can try, but there's no controlling it," says Robert Thompson, a pop-culture expert at Syracuse University in New York. "In this age of digital media, which puts everything up for grabs, legacy does not mean only what is etched in stone by officially sanctioned memoirs and recordings, but what people do to interpret it."

Which means that from now on, when there's a legacy to be preserved – and profited from – estate holders will have to choose their battles.

This came into play recently with a new edition of Guitar Hero that depicts a virtual Kurt Cobain "performing songs" he did not write and never sang, which his former bandmates Krist Novoselic and Dave Grohl said was "hard to watch." In a written statement, they said they "have no control" over his "name and likeness," which belong to estate owner Courtney Love. (Activision, which manufacturers Guitar Hero, said they received Ms. Love's permission, which she denies.)

"Once an artist is dead ... things get frozen and sacred in ways that maybe [they] weren't before," says Douglas Masters, a Chicago attorney charged with defending the intellectual property estates of Elvis Presley and Muhammad Ali.

In the case of Presley, Mr. Masters says that although the estate is "willing to license pretty much anything ... there's still some sacred cows" that are off limits, such as alterations to Graceland, Presley's Memphis estate, or the use of unflattering images. The challenge, he says, is that it's much harder to stop unauthorized activity.

What is at stake in the Jackson case is the wealth of his holdings. Even with his family at war with the executors of his estate, Jackson's posthumous earning potential is starting to become evident. Since his death, business deals have fetched $100 million, almost double the amount his estate earned in 2008. Jackson's holdings not only include his song catalog but also a 50 percent stake in Sony/ATV. Sony is releasing a "new" Jackson single this month, as well as a documentary from his aborted tour.

His family is also battling concert promoter AEG Live, which is planning a two-year, three-city memorabilia exhibition starting later this month to accompany a film – all expected to earn his estate $6 million.

Ultimately, the more lasting tributes may come from fans, says Bukvic. "The key issue is engagement. It's a more genuine form of attention than the media could ever generate."