Endangered plants you'll likely never see

Loading...

As a botanical illustrator, Wendy Hollender is accustomed to working everywhere, from sultry tropical jungles to dusty hillsides knee-deep in grass.

In 2008, in search of rare plant subjects, she ventured to Hawaii where, by chance, a critically endangered scentless Hawaiian mint was on the cusp of blooming. When Ken Wood, a conservation biologist at the National Tropical Botanical Garden asked if she would render the yet to be described plant known from just 15 wild individuals, she couldn't resist.

That drawing, along with several she made of exceptionally rare forms of hibiscus, are on display at the exhibition "Losing Paradise? Endangered Plants Here and Around the World." Housed at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C., through Dec. 12, the show is a collection of botanical drawings of 44 of the world's rarest plants, half of them native to the United States.

The 41 artists from five continents in the exhibition are peddling an old craft with the simplest of tools, but one that still has a profound importance for science and conservation.

Armed with colored pencils, a ruler, eraser, magnifying glass, and pad of paper, Hollender captured the scarcely known purple blossoming mint on paper just as its curved floral tubes swelled with life. The timing, as Mr. Wood recalls, "was perfect, just magic."

Part of the beauty of using simple tools like pencils and paper, Hollender says, is that it allows for maximum mobility and the freedom to concentrate on her subjects. Undistracted by the medium, she says, "I feel as if I am 'hooked up to my plant' when I work."

Back in New York, where Hollender is coordinator for art and illustration at The New York Botanical Garden, she submitted her five rare plant illustrations (the four Hibiscus drawings and the mint, known as Stenogyne kauaulaensis) to the juried show, a project of the American Society of Botanical Artists (ASBA).

Among the endangered species featured in the exhibit are some of the most intriguing plants you'll probably never see: the pima pineapple cactus, the ghost orchid, the longolongo, the tupa rosada, and Begonia samhaensis. Their respective native habitats are equally captivating: Mexico's Sonoran desert grasslands, the Florida Everglades, Fiji, Chile's temperate rain forests, and Yemen's wind-scorched Socotra islands.

The artists who captured these plants in ink, paint, and colored pencil were required to search for their own subjects. Any plant was acceptable as long as it was listed as threatened or endangered by a state, federal, or international government body or the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN).

Just finding a plant to depict was, for some artists, a multiyear effort. Take the elusive pitcher's thistle (Cirsium pitcheri). Artist Derek Norman spent five years searching for the threatened plant with cream-colored, fragrant blossoms, which flowers and produces seed only once before dying.

Mr. Norman's subject, found infrequently on beaches and dunes of the western Great Lakes, mostly in Michigan, is vulnerable to human impacts like shoreline development and recreational vehicles.

In Norman's own story of drawing the pitcher thistle he recalls spending two "sweltering, hot, humid days in the company of biting flies, a colony of ants, and the occasional attacking red-wing blackbird" as he drew a highly detailed pencil illustration of the plant in situ.

Such perseverance and dedication to capturing an image of fleeting botanical beauty is admirable but, some might ask, in the digital age why not snap a few dozen high-resolution photos instead?

Botanical artists and scientists say there is no comparison. Hollender explains that a hand rendering of a plant allows the artist to emphasize important features and select an optimum composition that is descriptive and aesthetically pleasing in a way the camera cannot. Artists can depict light or even a certain state or condition of a plant to create an ideal image.

Botanical art, no matter the medium, is not merely about the reproduction of physical facts, says Carol Woodin, coordinator of ASBA exhibitions and a painter herself. "Details are important, but there is a human interpretive element and the hope of depicting the dynamism of a given plant that is inherent in botanical art."

A botanical artist seeks to "draw the viewers in, stopping them momentarily, disengaging them from the jangle of modern life to pause and take a breath," Ms. Woodin says. "Perhaps through the depiction of these endangered plants we can captivate viewers with the strangeness and beauty of each form."

Peter Raven, a renowned botanist and advocate for protecting biodiversity who wrote an introduction about the importance of plant conservation for the exhibition, says plants have a complex beauty that can be interpreted differently depending on the imagination and vision of the artist.

"Art concerning plants is thus like all art, subjective and interpretive. In a scientific sense, drawings of plants can convey much more about the essential characteristics of a plant than any other form of representation, but paintings and digital images can contribute other aspects," he says.

Dr. Raven, who Time magazine named a "hero for the planet," and who is president of the Missouri Botanical Garden, sees botanical art's value to science and conservation in its ability to "intrigue people and nourish their intrinsic interest in plants."

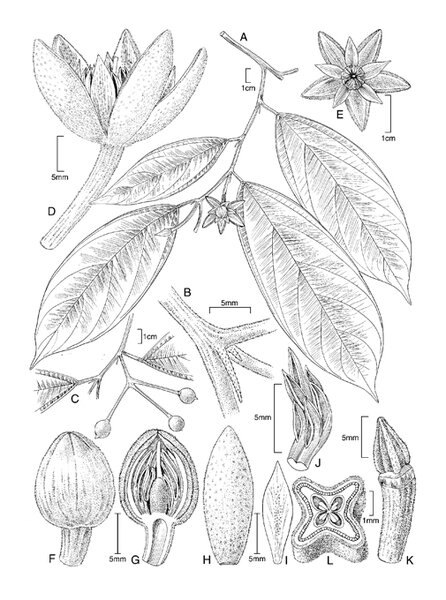

From a practical viewpoint, botanical art also offers insight into the plant world necessary for science. Alice Tangerini, a veteran staff illustrator for the Smithsonian's department of botany, says, "My drawings serve as eyes for botanists and can communicate a physical structure visually to anyone in the world, regardless of language. If I've done a good drawing, a botanist doesn't even have to read the description."

Ms. Tangerini, whose audience is primarily botanists, specifically taxonomists, uses waterproof ink on archival quality drafting film that is resistant to heat, light, and water. This, along with a smoothness and the translucence of film make for a preferred drawing surface.

Often she is the first person to ever draw a particular plant, and so her illustrations are crafted to depict the perfect example of a plant. She can omit natural external damage and emphasize a particular characteristic such as microthin hairs or minuscule bumps that would be all but invisible to even the best camera. Her illustrations are based on various sources and supplemented by photography but, Tangerini says, cannot be replaced by it.

Working almost exclusively from dried herbarium specimens, Tangerini says she takes dead plants and makes them look alive again. These black-and-white line drawings are intended to be used for decades, if not centuries, as primary reference material for identifying plants.

Describing her own work, Tangerini – who drew an extremely rare Mexican tree called Mortoniodendron uxpanapense for "Losing Paradise?" – is anything but sentimental. "We're just interested in morphology here, not color or how pretty something looks."

Yet her pen-and-ink illustrated plates, which can include up to 15 drawings of a plant's parts at varying degrees of magnification and in different stages, capture the natural beauty of plants increasingly threatened by invasive species, climate change, and other human factors.

With a growing awareness and concern for conservation (2010 is the United Nations' International Year of Biodiversity), there's a renewed interest in botanical art by artists and the public, Woodin says. She adds that viewers unfamiliar with botanical art are frequently struck by the level of detail, complexity, and simple beauty on display in each work.

"There are 41 different artists in the show," Woodin says. "So there are 41 different ways of depicting and viewing the plant world, from quillworts and cycads to orchids. This makes for a fascinating experience and a realization that the art form continues to be relevant and ever-sprouting."