The high-flying art market

Loading...

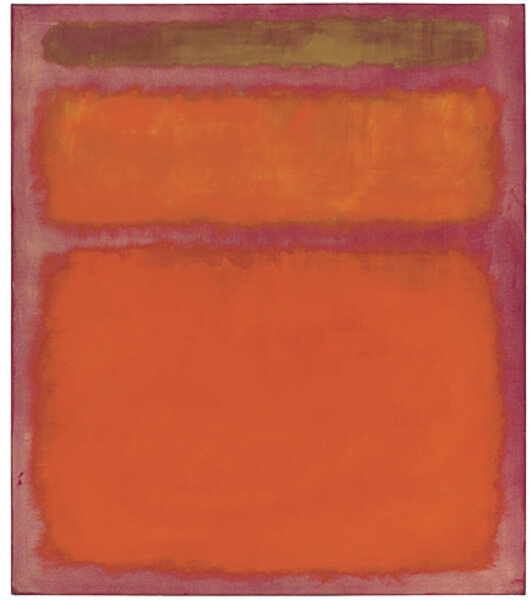

This may sound counterintuitive, but the wobbly world economy is driving fine art investment like never before. Most people are short on the kind of disposable income required to purchase notable works of art these days. But the deep-pocketed 1 percent are going at art auctions hammer and tongs, ponying up record-busting sums across the fine art spectrum. Rich investors are now seeing art as a stable form of wealth management in uncertain times, especially when compared with the imperiled dollar or euro. And a lot more fun, apparently. As artist John Baldessari told The Economist, "you can acquire something much better to look at than a stock certificate." Paying a record price is considered a smooth move, fueling both the value and allure of the work, as well as the buyer's. Case in point: At an art auction at Christie's last spring, 41 works sold for more than $1 million apiece; nine for more than $10 million. In May, the 1961 Mark Rothko painting "Orange, Red, Yellow" sold for $86.9 million. And Andy Warhol's "Eight Elvises" recently garnered a cool $100 million, thank you very much.

Now enter the Chinese, who know a good investment when they see one. They have quietly been paying top prices for masterpieces, and China has just recently surpassed the United States as the world's largest market for fine art. But the top is the top.

What about the rest of the market?

The news for the other 99 percent is not so hot. With all the serious money and buyers crowded onto the tip of the art market iceberg, the rest of it is crumbling because of lack of exposure and dwindling sales. Few new artists are deemed collectible, and many galleries have closed their doors. Here in Boston, nine major galleries have shuttered in the past four years. Several had been displaying art since the 1950s. The ease of browsing, locating, and buying works on the Internet is a pernicious gallery slayer. So is the bunnylike proliferation of art fairs. Works priced between $500 and $1,000 still hold appeal for younger collectors, but many artists who are down-pricing report earnings 50 to 80 percent less than what they were making before the recession of 2008 knocked the art market – and potential customers' "mad money" – for a loop.

For the moment, at least, big-name buyers and sellers will make millions, and no-name artists will continue to make art, just for the love of it.