GIFs get a new life as pop art

Loading...

Recall, dear reader, the infant Web. Modems squeaked and whirred, and AOL ruled supreme. Devoid of videos, the nascent Internet was static and textual. The Graphics Interchange Format, or GIF, was an exception. An icon of Web 1.0, the low-resolution, animated image fell out of favor as bandwidths grew to support more sophisticated online videos. But the GIF (say “jiff”) has experienced a renaissance of late, as bloggers, advertisers, and artists have found new ways to utilize this digital relic.

“In content creation, there’s always been a way that people have appropriated things as identity markers,” says Lee Rainie, director of Pew Research Center’s Internet & American Life Project. He compares animated GIFs to the way people use emoticons or unique e-mail signatures as a form of personal expression.

GIFs arrived in 1987 and became a fad among early Internauts. They decorated GeoCities pages with gaudy, looping animations of “under construction” signs, a spinning Earth, and a dancing baby made famous by the hit television series “Ally McBeal.” Then, as quickly as they had arrived, GIFs became design faux pas as streaming video and high-quality images rendered them woefully passé.

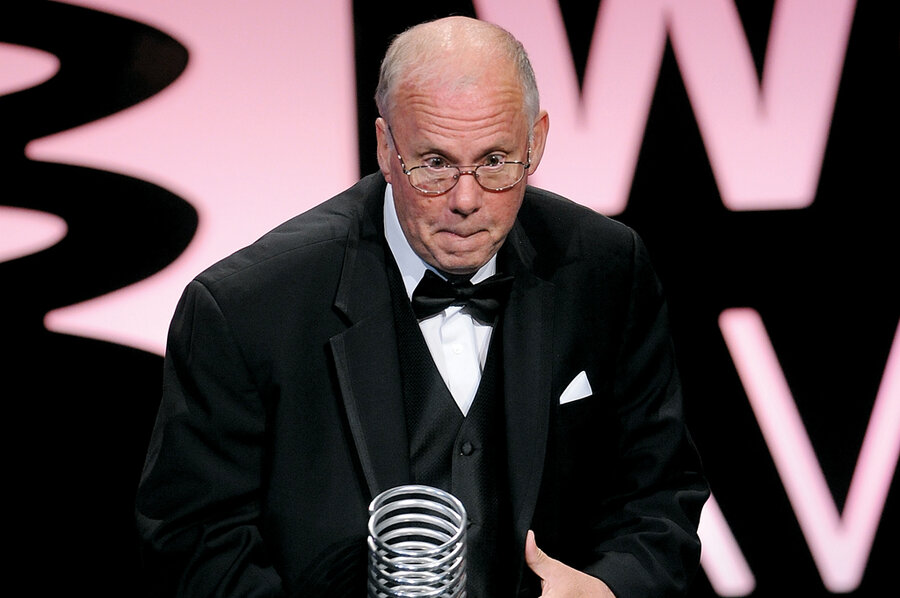

But the GIF is back in the digital lexicon, even earning the title “word of the year” from the Oxford American Dictionary in 2012. This May, Steve Wilhite, the GIF’s inventor, accepted a lifetime achievement award at the Webby Awards, the Internet’s Emmys.

The resurgence is partly owed to the blogging platform Tumblr, which lends itself to the easily made and shared nature of GIFs. Users post hypnotic loops lasting only a few seconds from popular YouTube clips, sports replays, or TV shows, coupled with text equating the scene to everyday affairs. For example, on #whatshouldwecallme, a popular Tumblr site, the words “When there’s an all-staff e-mail at work saying there’s food in the pantry” are animated by a GIF of the “Scooby-Doo” gang hurrying across the screen.

Artists push the medium beyond pixelated similes, creating what is more than a photo but not quite a movie. Collaborators Jamie Beck and Kevin Burg use GIFs to animate a detail of an otherwise still photo – a man turning the pages of a newspaper, or the breeze blowing through a woman’s hair. The resulting “cinemagraph” is subtle and poetic – the antithesis of early one-dimensional GIF expressions. Microsoft, Google, and others have commissioned work from the pair. Their interest amuses Mr. Burg.

“I used to create [GIFs] in the mid-’90s for fun when I was 12 years old,” he says. “It’s funny that something I once dabbled in is now my career trajectory.”