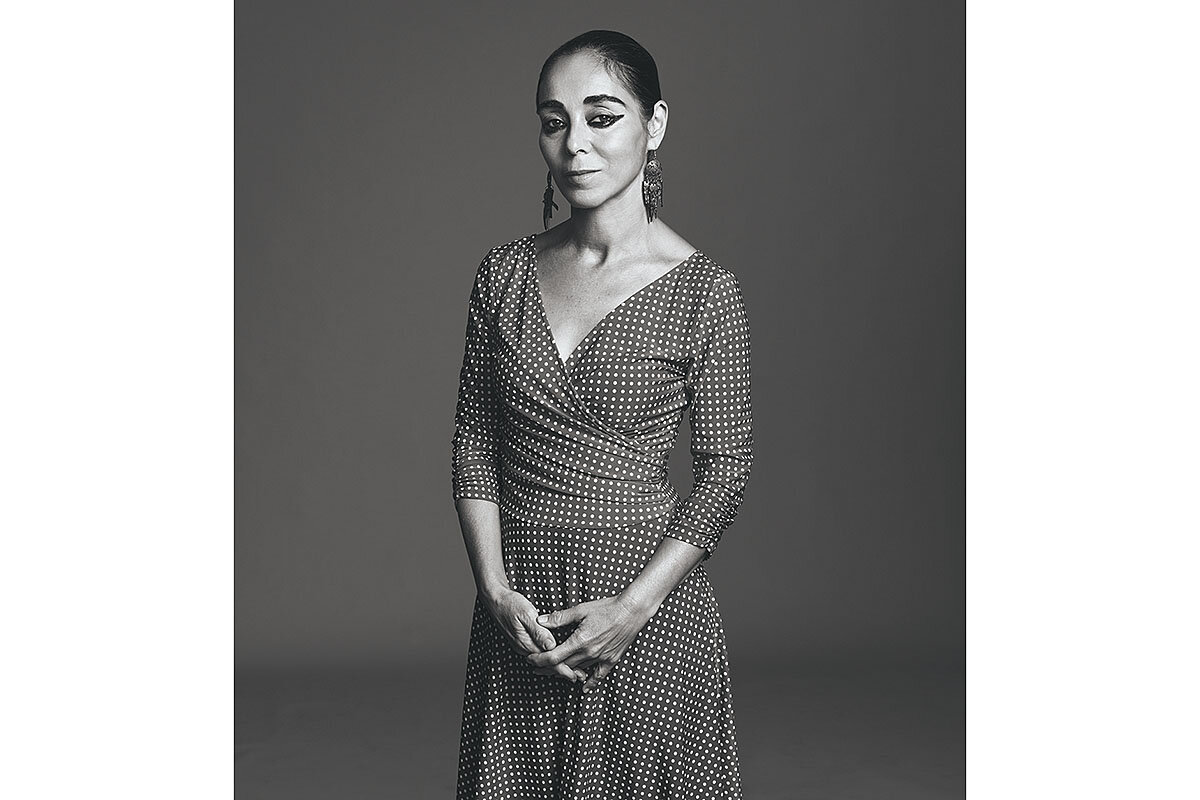

An artist embraces her Iranian past and her American present

| Los Angeles

Iranian American artist Shirin Neshat doesn’t think political art should be obvious and preachy.

“It’s wrong to tell people what’s right and what’s wrong. But it is possible to make art that makes people think about important issues in a whole new way and have new insights,” she says.

Over a 30-year career, Ms. Neshat has mined her feelings of dislocation as an exile. She’s created haunting photographic portraits, surrealistic video installations, and atmospheric short films with collaborators such as actress Natalie Portman and composer Philip Glass. In 2018, she was commissioned by the National Portrait Gallery in London to create a portrait of activist Malala Yousafzai. She’s won numerous international art and film prizes.

A retrospective of her work, “Shirin Neshat: I Will Greet the Sun Again,” recently ended its run at The Broad in Los Angeles and is expected to travel to the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, in Texas, early next year. It traces Ms. Neshat’s evolution from depicting Middle Eastern subjects to her latest projects focusing on her adopted country. (She became a U.S. citizen in 1986.)

For her, the struggle is creating a balance between “being politically conscious – tackling the real issues we’re facing – and allowing multiple interpretations so people can think about it and take away whatever they wish.”

Her work erects bridges rather than walls, according to Farzaneh Milani, chairwoman of the department of Middle Eastern and South Asian languages and cultures at the University of Virginia. Ms. Neshat’s poetic and conceptual art is like “a magic carpet that takes us to unfamiliar territories,” she says, freeing us from “our mental, intellectual, and political ghettos.”

In “Land of Dreams” from 2019, the artist combines photographic portraits of people in New Mexico – immigrants, Native Americans, ordinary people from all walks of life – with videos that elicit their dreams and fears. The project attempts to create a portrait of America at this moment, in the middle of the hostile rhetoric toward immigrants and asylum-seekers. Her message, she says, “is to emphasize the diversity in this country between multiracial ethnicities and the shared humanity that defines America.” For Ms. Neshat, who is proud to be both an American and an immigrant, “the American identity is this multiplicity and hybridity.”

Her artistic epiphany began when she traveled back to Iran in 1990 after living in the United States for 15 years. “It was quite traumatic,” she says. The Islamic Revolution in 1979 and the Iran-Iraq War in the 1980s, which had separated her from her family, had altered Iranian society.

“The country had really transformed from what I recalled the last time I was there under the shah [Mohammad Reza Pahlavi], which was modern and very liberal,” she says. Ms. Neshat was shocked to discover all the women veiled, encased head-to-toe in black. The country seemed to have traveled backward in time from a colorful, secular society to a conservative theocracy.

On the trip, she encountered images of Iranian women glorified by the state as martyrs who’d fought against Iraqi invaders. She found it “terrifying but also interesting and exhilarating,” she says. Even while these female warriors’ civic rights were curtailed, they could still bear arms. They were both militant and silenced. The paradox fascinated her.

When she discovered that Iranian women had lost their voices, Ms. Neshat found hers.

Until the trip to Iran, she had been living in New York, co-directing a nonprofit experimental space called Storefront for Art and Architecture with her then husband, Kyong Park, and raising a son. She had pursued art studies at the University of California, Berkeley, but she was not then producing art.

“At the time, I didn’t have an art career,” she recalls. “I didn’t have an audience in mind. Everything just grew very organically. The revolution was the core of my subject, understanding how the country became Islamicized, and then the subject of martyrdom.”

She began sketching hands and feet, and writing in Farsi script on top of them. Eventually, she thought, why not just use photography? Later, she moved on to photographs of Iranian women, who are shown covered except for their eyes and sometimes their faces. Some carry weapons. They look unblinkingly out at the viewer. The artist inscribes the faces in the photographs with decorative flourishes and the words of contemporary female Iranian poets. Ms. Neshat gives words to what the women have experienced, depicting their dignity as well as their defiance.

The series of photographic portraits, “Women of Allah,” brought her international attention.

Hadi Ghaemi, executive director of the nonprofit Center for Human Rights in Iran, says that “Women of Allah” “is about how women during the war were propelled into roles they never had before.” The series effectively overturns stereotypes, especially that of “the subservient, obedient housewife or woman in Iran,” says Abbas Milani, director of the Hamid and Christina Moghadam Program in Iranian Studies at Stanford University.

Ms. Neshat uses art as a tool to inform, provoke, and perhaps even liberate and heal.

She provides a fresh perspective on the places where she’s worked in addition to Iran, such as Turkey, Morocco, Egypt, Azerbaijan, Mexico, and the U.S. Seeing the world through her eyes requires a revision of assumptions.

“Through difficult encounters or interacting with something you don’t understand, if you allow yourself to take a crack at understanding it, art can bring an incremental change in perspective,” says Ed Schad, who curated Ms. Neshat’s retrospective at The Broad.

Ms. Neshat’s art embodies an immersive, expansive, and transnational view of humanity.

“I cherish my relationship to American culture,” the artist says. “I live a double life, a life between East and West, and Iran and America, since I was 17. You maintain something of your past, but then you adapt to where you are living.”