Supreme Court justices' families less nuclear, more diverse like US

Loading...

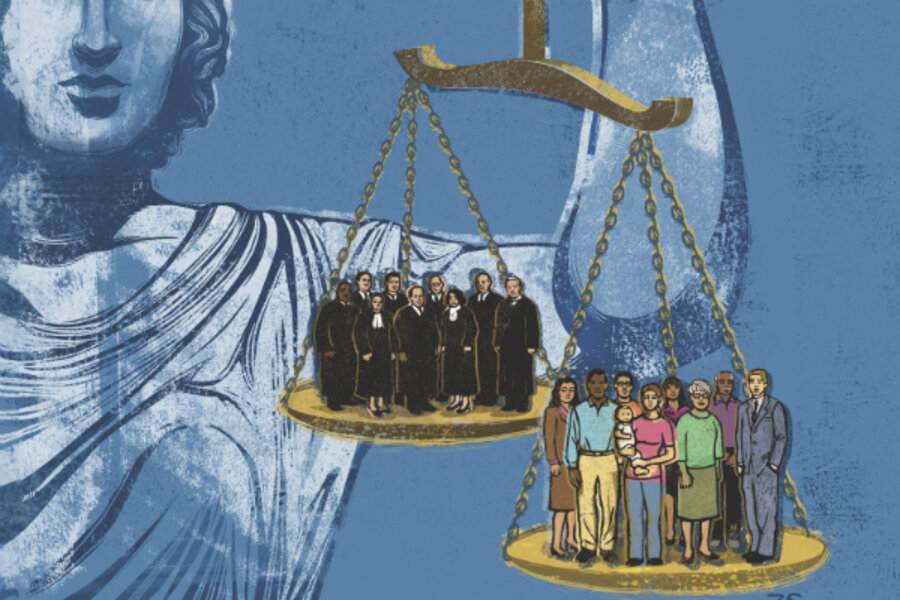

With their Ivy League pedigrees and East Coast addresses, Supreme Court justices often are rightly described as unrepresentative of the nation. But in one area, the justices look a lot like the rest of America.

Members of the court have firsthand experience with divorce and adoption, as well as making it alone without ever getting married. Just five of the nine justices have been married once and have had biological children with their spouses.

"The diversity of the family lives of the justices mirrors the diversity of American families overall," said Andrew Cherlin, a Johns Hopkins University sociologist who studies families and public policy.

These varied family portraits of the justices are somewhat at odds with the arguments of gay marriage opponents who stress the unique ability of heterosexual couples to have babies as a reason to uphold bans on same-sex marriage.

The briefs defending California's Proposition 8 gay marriage ban and a federal law denying benefits to legally married gay couples are sprinkled with references to the ideal family as having a mother, a father, and biological children.

"Proposition 8 thus plainly bears a close and direct relationship to society's interest in increasing the likelihood that children will be born to and raised by the mothers and fathers who brought them into the world in stable and enduring family units," the provision's supporters say.

The conservative, public-interest Thomas More Law Center in Ann Arbor, Mich., puts it this way: "Reserving marriage to a man and a woman thus reflects the inherent distinction between those pairs capable of engaging in the act which can produce human offspring, and those pairs which cannot."

The two justices who have adopted children are considered likely votes against gay marriage. Chief Justice John Roberts is the father of two children, Jack and Josie, both 12. They were adopted four months apart as babies in 2000, after Roberts and his wife, Jane, then 45, spent several years trying to adopt. The Roberts family discussed the adoption for a biography of the chief justice that was aimed at young readers and published in 2006.

Justice Clarence Thomas and his wife, Virginia, took custody of Thomas's grandnephew, Mark, when he was 6, in 1998. Soon after they were married in 1987, the Thomases decided they would not have children of their own, author Ken Foskett wrote in his biography, "Judging Thomas." Mark's father had been in and out of legal trouble and his mother was raising three other children on her own. Thomas also has a biological child from his first marriage, which ended in divorce.

Justice Sonia Sotomayor also is divorced, while Justice Elena Kagan has never married. Neither has children.

The justices' personal lives may not often play a role in the way the court decides cases, but they cannot completely set aside their own experiences and circumstances. Both Sotomayor and Thomas were beneficiaries of affirmative action programs that were intended to boost minority enrollment in higher education. On the court, Thomas has voted to get rid of the use of race in admissions and other areas. Sotomayor has yet to cast a vote on the topic, but she has spoken much more positively about affirmative action than has Thomas.

The justices also are not immune to considering how they might be affected by the course one side or the other is advocating in a dispute before them. Last year's case involving the placement of a GPS device on a car seemed to take a turn against the government when a Justice Department lawyer asserted that federal agents could track the justices' movements the same as any other person's, without obtaining a judge's approval.

"So, your answer is yes, you could tomorrow decide that you put a GPS device on every one of our cars, follow us for a month; no problem under the Constitution?" Roberts said during the argument in US v. Jones.

Cherlin, who does not follow the high court especially closely, wondered whether the gay marriage cases might take on a similar dynamic. "If justices consider their own family lives in these cases, it may change the way they rule," he said.

Gay marriage opponents said they are not worried about the votes of Roberts and Thomas.

"You're looking at what is the best course societywide to get you the optimal result in the widest variety of cases. That often is not open to people in individual cases. Certainly adoption in families headed, like Chief Roberts' family is, by a heterosexual couple, is by far the second-best option," said John Eastman, chairman of the National Organization for Marriage. Eastman also teaches law at Chapman University law school in Orange, Calif.

Thomas has dissented from two major decisions in favor of gay rights in 1996 and 2003. The latter case, Lawrence v. Texas, concerned the state's anti-gay sex law. In a short, separate opinion, Thomas described his view of the difference between a judge and a legislator.

He called the law "uncommonly silly" and said he would vote to repeal it if he were a Texas lawmaker. But as a federal judge, he said, he was compelled to vote to uphold it.

Both sides in the current cases have spilled a lot of ink about the relevance of another high-profile Supreme Court ruling, the unanimous decision in 1967 that held states could not prohibit interracial marriages. Gay marriage supporters point to Loving v. Virginia as an important precedent in their favor. Opponents say the case is not of much help to the court because race never had a central role in the definition of marriage.

Whether or not Thomas finds any important legal connection between that decision and the gay marriage cases, the personal connection is undeniable. Thomas, who is black, and his wife, who is white, live in Virginia.