Tracking down the origins of ‘witch hunt’

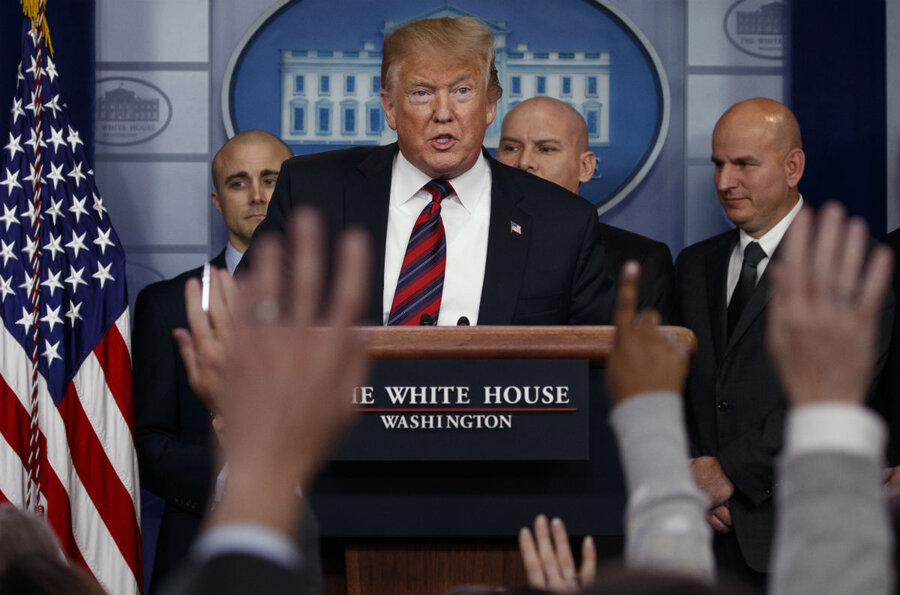

President Trump tweeted about a witch hunt more than a hundred times last year. It is debated in the news and across social media: Is the Russia investigation a witch hunt or is it not a witch hunt? I was hearing “witch hunt” so often that a few weeks ago I experienced semantic satiation, in which repetition causes a phrase to lose meaning and be perceived as nothing but empty sounds. Then I began to wonder, what is Mr. Trump actually saying when he uses those words?

Obviously, the term refers to real, historical hunts for witches that occurred sporadically across Europe and later in America from the 15th to 18th centuries. Like wildfires, anxieties about witches would flare up in this period, following a rough pattern. Misfortunes would happen in a village, and some women on the fringes of society – an old herbalist who lived alone; in Salem, Mass., the slave Tituba – would be accused of causing them through magic. These women would be imprisoned, sometimes tortured, and asked to name their accomplices. Sometimes they could prove their innocence by undergoing a “trial by ordeal” – being thrown into a pond to see if they sank (innocent) or floated (guilty) – but often they were executed without opportunity to refute the charges against them.

The self-proclaimed witchfinder general of England, Matthew Hopkins, was responsible for one of the largest witch hunts, executing more than 300 suspects in the 1640s. He preferred to say that he “discovered” witches, however, and witch hunt only became the term of choice in the late 19th century.

George Orwell, author of “1984,” was one of the first to use the term metaphorically: In the 1930s, he called “trumped up accusations” by one group of communists against another a witch hunt. The idea of political witch hunts spread quickly in the 1950s. Investigations by Sen. Joseph McCarthy and others to discover secret communists in the US government, in Hollywood, and at universities were frequently denounced as witch hunts. Use of the term implied that the fear of communism in the United States was in fact hysterical and overblown, and that, like alleged witches in the past, suspected communists were unjustly accused, unable to defend themselves fully, and forced under great pressure to reveal the identities of others.

Is the Russia investigation a witch hunt? Is the metaphor appropriate? In a sense it doesn’t matter. Sometimes hearing words over and over doesn’t turn them into meaningless syllables, as with semantic satiation. Instead, it makes them seem true, a phenomenon known as “the illusory truth effect.” The more the president repeats “witch hunt,” the more likely it sounds, whatever the facts.