The new celluloid heroes

Loading...

Amid the fanciful 3-D technology and the story of two children navigating the contrarian world of adults, Martin Scorsese's film "Hugo" pauses midway through and shows audiences why preserving early cinema is a cultural necessity.

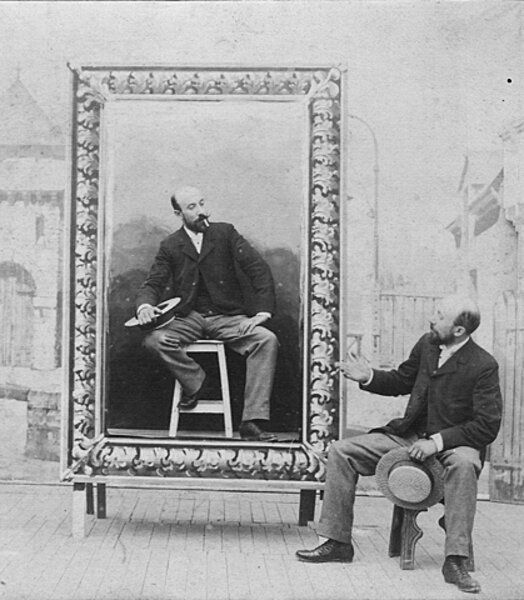

The film's real subject, of course, is the French film auteur Georges Méliès, whose body of work – 531 films – largely perished in his lifetime, creating personal agony and professional irrelevance until a retrospective nine years before his death allowed him the wider recognition his work deserved.

His is an allegory familiar to many involved in film preservation today. "Hugo" and the recent Oscar topper "The Artist" both pay homage to the artistic beauty of early cinema, but they arrive at a precarious time for film as a medium. Digital cinema is forcing exhibitors and studios to upgrade celluloid film systems with new technology designed to offer audiences better screen resolution, contrast, and opportunities for 4-D immersion experiences – and to save studios $1 billion in printmaking fees and shipping costs annually.

The transition is considered the definitive end for celluloid, a format considered the foundation of the film industry for 100 years. As fewer theaters are equipped to show traditional film, there become fewer opportunities to view films of the past, a fact that worries film preservationists who are rushing not only to save old films from deteriorating, but also to find films that have been lost. Their absence has diminished our cultural memory.

"I find it ironic that the interest in film preservation has grown exponentially precisely at the time when film as a medium is about to be replaced by digital technology. In other words, cinema is being taken seriously now that it's almost dead," says Paolo Cherchi Usai, senior curator at the George Eastman House, a film archive and school of film preservation in Rochester, N.Y.

The Library of Congress estimates that only 20 percent of feature films made in the United States in the 1910s and '20s survive today; of those features produced before 1950, only half exist. The loss of these countless shorts, silent features, and documentaries not only deprives us of our past, but also denies us the chance to experience the artists and stories that once filled theater screens.

One example: We know actor Emil Jannings won the first-ever Academy Award for best actor in 1929 for the film "The Way of All Flesh," but we'll never see his performance because copies of the film no longer exist.

The challenges of preserving film are many: Many studios kept poor records of films they produced, making it difficult to document which films need scouting. Nitrate film, the standard before 1950, was not just combustible, a characteristic that led to several infamous studio archive fires, it also contained silver, which made it more valuable than the images it contained.

One reason more than half of Méliès films are gone: The French Army confiscated and melted his prints during World War I to retrieve the silver. The rest ended up as raw material for boot heels.

"At the time, studios didn't realize that the films could be exploited for later commercial use," says Jeff Lambert, assistant director of the National Film Preservation Foundation in San Francisco, which distributes grants to archives for preservation efforts. "Now when films are made, studios are already planning the DVD, cable, and Internet-streaming release. So they now all have really great preservation arms in place to watch out for the heritage they're creating. But that wasn't always the case."

Film preservationists are not just technicians; they are often also curators in determining, given budget constraints, which films should be restored and where they should be made available for new viewing.

"Preservation is absolutely important, but we really don't consider it preservation until the public has access to the material," Mr. Lambert says.

Given the current fate of mechanical film projection, new platforms are emerging for early archival film prints. Online streaming, DVD collections, and film societies now do the work. Jeff Masino, founder of Flicker Alley, a DVD distribution company in Los Angeles that recently released a celebrated box set of just under 200 complete Méliès films, says the continued evolution of how people view movies is only good for preservation.

"The technology in the last 5, 10, 20 years has allowed people to become more literate about film, which has also contributed to the renewed interest in silent films," he says.

Besides home releases that curate lost auteurs, genres, and actors, the ultimate way to experience early cinema might be at a local movie theater operated by a film society. Such preservationist groups work, often unpaid, with national film archives and private collectors to get the films before a new public.

Viewing film "has to be a social thing. It has to be people coming together doing something that individuals can't," says Kyle Westphal, a founder of the Northwest Chicago Film Society, a weekly film series of little-seen or restored silent and early-era films. Besides hunting down prints, ordering them from archives and staging the screenings, the organization creates painstaking background material of the film for viewers to provide a sense of the history that went into keeping them in circulation and relevant for showing today.

"Ultimately we do think of ourselves as an educational organization. If there's an interesting story about a film's preservation, we put it out there and talk about it," Mr. Westphal says. "If there weren't avenues showing these films, why preserve them?"

As fewer venues show archival prints and advancing technology makes home screenings a niche outlet for viewing, the future of appreciating early cinema may take place in museums or art centers.

Mr. Usai, who believes there is a "distinctive beauty of the moving image" on mechanical film, says he is optimistic because soon there will be an "opportunity to give film as an object the same kind of dignity that has been given to painting, sculpture and architecture."

"The day when film will no longer be made, at that point, the exhibition of a beautiful 35mm print of 'Lawrence of Arabia' will be perceived as a special event equal to the presentation of a Picasso painting," he says. "I see nothing wrong with that."