'I Am Not Your Negro' shows that the world today is poorer for not having James Baldwin’s views

Loading...

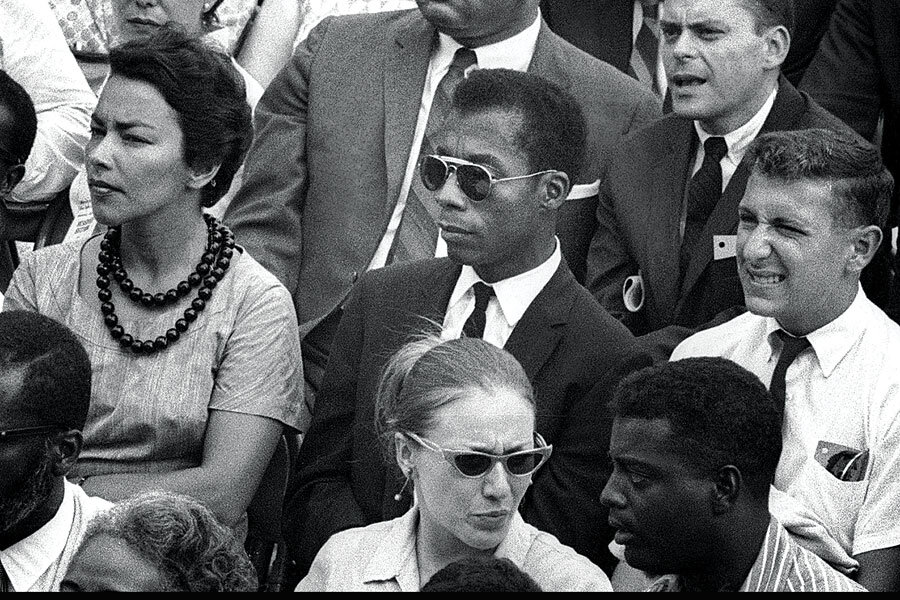

In 1979, James Baldwin’s literary agent, Jay Acton, asked him to write a book about the author’s three slain friends, Medgar Evers, Malcolm X, and Martin Luther King Jr., all dead before the age of 40. Baldwin’s response was a 30-page letter describing why he felt he could not write such a book – which he then attempted to write (titling it “Remember This House”) but left unfinished at his death in 1987. Baldwin’s words from that letter, plus many excerpts from his magisterial essays, make up the core of the spoken soundtrack for Raoul Peck’s Oscar-nominated documentary “I Am Not Your Negro.” Alternately discursive, philosophical, agitprop, and accusatory, the film itself is a species of essay.

The movie’s defining quote is, “History is not the past, history is the present.” (All of the words in the film, spoken by Samuel L. Jackson with understated gravitas, are Baldwin’s.) To this end, Peck – a Haitian-born filmmaker who made the celebrated “Lumumba” (2000) and has a dramatic film about the young Karl Marx slated for release later this year – consistently draws parallels between race relations today and Baldwin’s impassioned writings about being black in America during his time, inserting newsreel clips from the events that transpired in Ferguson, Mo., and Baltimore; Black Lives Matter protests; and much else.

For Peck, the progress that has been made in black-white relations since Baldwin’s time is illusory, a sham. He opens the film with a clip from a 1968 interview with Baldwin in which Dick Cavett asks him, “Why aren’t Negroes more optimistic? It’s getting so much better.” To which Baldwin, speaking in that voluble, drawling baritone that was so unmistakably his, answers, “It’s not a question of what happens to the Negro. The real question is what is going to happen to this country.”

Baldwin’s essays and filmed public appearances are the documentary’s lifeblood. We are continually prodded to recognize his prescience. Speaking of white racists, he says, “These people have deluded themselves for so long that they don’t think I’m human.” They cannot “face the fact that I am flesh of their flesh.”

Baldwin, despite his incendiary words, was far from doctrinaire, and the film allows for his equivocations. He talks about the white schoolteacher, Orilla Miller, who gave him, as a 10-year-old, books to read and took him to plays, shows, and movies. “I loved her, of course, and absolutely.... It is certainly partly because of her, who arrived in my terrifying life so soon, that I never really managed to hate white people.”

Neither was Baldwin a joiner, refusing to align himself with the Black Panthers or Black Muslims (“I did not believe all white people were devils”) or even the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People or the church. He had the ability to be both forthright and nuanced. Some of Baldwin’s insights, as they relate to popular culture, have the force of epiphanies. He describes the final scene in “The Defiant Ones” in which Sidney Poitier, playing an escaped convict chained to Tony Curtis’s white racist, jumps from a train and in an act of supreme brotherhood, sacrifices his freedom rather than leaving the white man behind. When the film played in theaters to white audiences, Baldwin writes, patrons applauded the gesture. Black audiences, by contrast, shouted, “Get back on the train, you fool!” Writes Baldwin: “The black man jumps off the train to reassure white people, to let them know they are not hated.”

It is not recognized often enough that Baldwin was, in addition to so much else, a great film critic. His deeply personal memoir, “The Devil Finds Work,” from which much of Peck’s documentary draws its film-related quotes, is a shining example of how Baldwin could utilize popular culture as a springboard to examine society’s core racial myths and beliefs. One need not endorse the passages of stridency in these writings to feel their force.

Peck, however, overplays his hand. It’s one thing for Baldwin to talk about the films of Doris Day as “one of the most grotesque appeals to innocence the world has ever seen.” It’s another thing to pair images of “Lover Come Back” with lynchings in the South. Or intercut shots from “The Pajama Game” with clips of black-white police brutality. Or show a clip from 2003’s “Elephant,” about a Columbine-like school massacre.

It should not be necessary to subscribe to Peck’s thesis – that, deep down, racial progress is a sham – in order to experience this film’s accusatory force. Would Baldwin, were he alive today, have endorsed that thesis? Most likely, but, as this film attests, we are the poorer for not having his troubling eloquence in these troubled times to bear witness. Grade: B+ (Rated PG-13 for disturbing violent images, thematic material, language, and brief nudity.)