‘The Apparition’ focuses on issues of faith, truth

Most religiously themed mainstream movies tend to be either of “The Da Vinci Code” variety or, much less frequently, something arty like Paul Schrader’s chilly, ascetic “First Reformed.” The French film “The Apparition” is a bit like both. Neither of these approaches is sustained or made truly satisfying, but at least there are ideas knocking around in this movie that, despite its overlong 144 minutes, are worth the time.

Jacques Mayano (Vincent Lindon) is a French investigative journalist recently returned from a Middle East assignment where he suffered an ear injury and his photographer colleague was killed, for which he feels (undeservedly) responsible. In the throes of post-traumatic stress disorder, blocking out the windows to his bedroom and barely communicating with his wife, Jacques is unexpectedly called upon by the Vatican for an assignment unlike any other he has ever attempted. Because of his scrupulous truth-digging reputation, a monsignor in Rome has chosen him to join an official canonical investigation committee to look into the claims of a rural 18-year-old French woman, Anna (Galatéa Bellugi), who says she has been visited in her small village by the Virgin Mary.

The news of the apparition has quickly spread partly because of the strenuous outreach of a publicity-hungry priest (Anatole Taubman). The Vatican, taken aback by the ensuing pilgrimages and commercialization – the selling of plaster relics, T-shirts, and the like – desires to confront Anna’s claims.

Vaguely agnostic, with no strong religious upbringing, Jacques is cynical about the entire enterprise but joins the committee as much to relieve his own despair as to seek the truth. He is joined by, among others, a psychiatrist and a priest highly skeptical of Anna’s claims.

The writer-director, Xavier Giannoli, puts us through the slow and steady paces of inquiry. The village’s head priest, Father Borrodine (Patrick d’Assumçao), is dead set against Anna cooperating with the questioners, but she, almost beatific in her bearing, complies. She seems transcendentally innocent, confounding any attempt to paint her as a charlatan. Despite the hoopla surrounding her, the TV cameras and zealous idolaters, Anna in no way seeks celebrity and is uncomfortable in its spotlight.

The big question, of course, is this: Is she telling the truth? Giannoli spends so much time dwelling on Jacques’s digging that naturally we expect the mystery to be solved by the end. And, in a sense, it is, though in a slapdash way that does not do justice to the ambiguities of what came before. The film starts out all-encompassing and ends up reductive. Perhaps he was afraid of making a “religious” movie that was too religious. But in dealing with such deep-dish issues as the provability or necessity of faith, why dumb down?

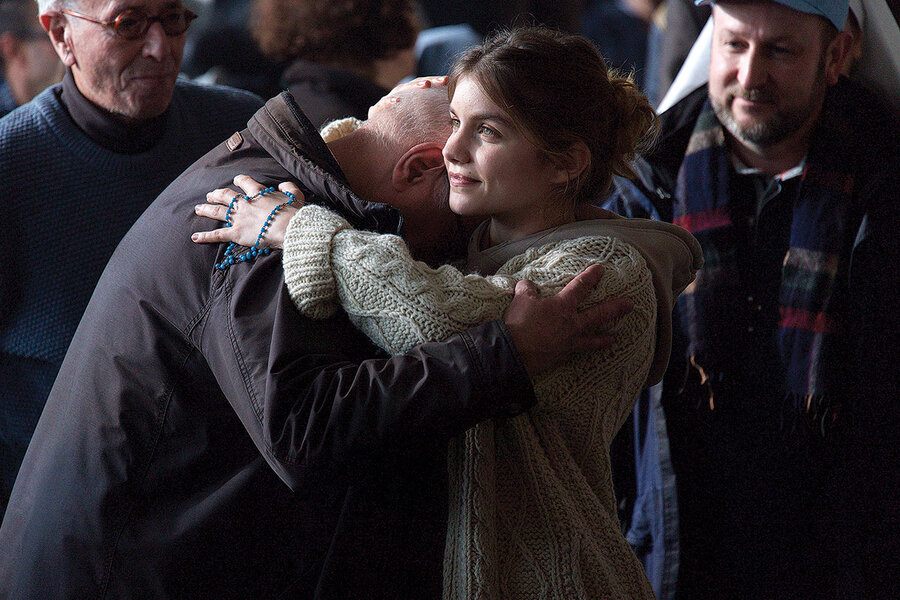

Although the film is at times overextended and pretentious, its strongest suit is the developing spiritual connection between Jacques and Anna. She takes it upon herself to absorb the “suffering of others,” and in Jacques, she sees a sufferer. As for him, he delves into her troubled background in nonreligious foster homes and conducts reams of interviews with those who knew her before she became a novitiate and devoted herself to God. He thinks her responses to sensitive questions sound scripted and grows increasingly skeptical of her claims. And yet he is drawn to her enigmatic aura of innocence. To Giannoli’s credit, he doesn’t uncomplicate Jacques’s relationship to Anna, who comes across as a virginal ideal, a source of salvation, and a puzzle to be solved.

Lindon is a master of zonked world-weariness and his gravelly bass-baritone could scrape glass. Bellugi does well by a role that too easily could have been slickly rendered. We look into Anna’s brimming eyes and, like Jacques, are at a loss to comprehend who she really is. Bellugi never gives the show away. We are left guessing until near the end.

A better movie would not have hinged its thesis so closely on Anna’s innocence. The film doesn’t fully allow for the fact that the issue of Anna’s veracity, or lack of it, is essentially a sideshow. For Giannoli, the possibility of disproving Anna’s claims becomes a shorthand for disproving the existence of God, and surely this is too slick an approach for such a complex experience. Grade: B+ (This movie is not rated.)