Unreleased Orson Welles film ‘The Other Side of the Wind’ arrives

Loading...

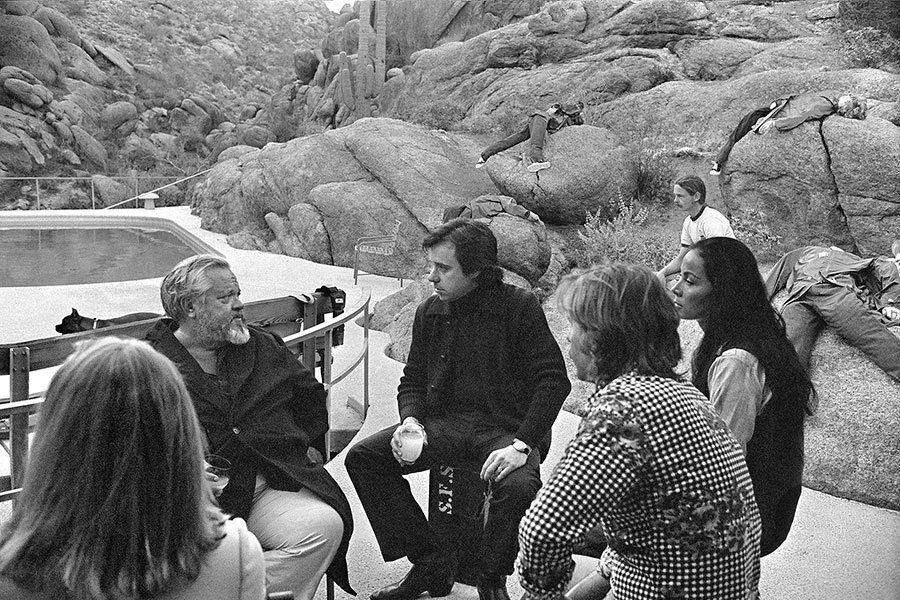

In the summer of 1970, Orson Welles embarked on a movie, “The Other Side of the Wind,” that he fervently hoped would bring him back into the Hollywood fold after more than a decade of self-imposed exile in Europe following a string of commercial flops. He believed the time was right for his reentry: The entrenched studio system that bedeviled him for so many years had given way to a new generation of filmmakers, many of whom were film school graduates influenced by Antonioni, Bertolucci, and the French New Wave, who were shaking things up and making movies that connected emotionally with a more adventurous audience. For many of these Young Turks, including Martin Scorsese and Francis Coppola, Welles was a deity. At 55, he was still young enough to believe he could fit into the fray.

As was too often the case in Welles’s career, things went horribly wrong. The financing for “The Other Side of the Wind” – which centers on a legendary, self-exiled director, played by John Huston, as he scrambles to complete the movie he hopes will revive his Hollywood glory – was so sporadic that it took Welles almost six years to finish shooting. And even then, with all the reshoots and cast changes and manifold other woes, the movie was not so much finished as abandoned, with the footage, owing to byzantine legal complications, locked up in labs and a vault in France for almost four decades. Welles died in 1985 without his cherished project ever seeing the light of a film projector.

Inevitably, “The Other Side of the Wind” became, for cineastes, the holy grail of the greatest movies never seen – until Netflix stepped in and, with the legal issues resolved, financed its completion.

By most accounts, the version of “The Other Side of the Wind” now being released simultaneously in theaters and on Netflix represents about a third of what Welles himself edited. The remainder, based on Welles’s notes, screenplay instructions, and hearsay from those present at the time, was mostly edited by Bob Murawski in consultation with Filip Jan Rymsza and Frank Marshall. A new (and beautiful) score was supplied by Michel Legrand.

And so, after all this hoo-ha, what do I make of the film? Welles has always been a cinema icon for me, and I approached this “new” movie as one might approach a new symphony by Beethoven. Having seen it, my overwhelming feeling is not exaltation but sadness. I look at this maddening pastiche and think of all the great movies he might have made. It was only five years earlier, after all, that he directed, with much financial tribulation, his Falstaff film “Chimes at Midnight,” one of his very greatest.

For Welles aficionados, and perhaps only for them, “The Other Side of the Wind” will function as a skeleton key to the themes and obsessions of his entire career. Jake Hannaford, the leonine character resonantly played by Huston (whom I also revere), is obviously a stand-in for Welles, although Welles himself denied it. He denied throughout his career any connection between the motifs of his movies, which usually centered on a powerful man brought low by betrayal, and the fraught circumstances of his life.

But there is a poignancy to Hannaford’s plight in this film, which takes place mostly at a 70th birthday celebration for him where he screens footage from his comeback opus, also called “The Other Side of the Wind,” for which he also seeks completion funds, in the midst of a buzzing maelstrom of hangers-on, predatory journalists, fawning biographers, acolytes (prominently Peter Bogdanovich, playing a hotshot movie director), starlets, yes men, no men, and cast members, some of whom, like his leading man (Robert Random), have already walked off the production.

Hannaford’s movie-within-a-movie is a wordless, languorous Antonioniesque fantasia, both tribute and parody, that features an enigmatic youth pursued by, and pursuing, a darkly alluring seductress, played by Welles’s lover and collaborator, Oja Kodar. (The sex scene between the two, shot inside a car during a torrential downpour, is one of the most carnal scenes in movies and also perhaps the only flash of eroticism in Welles’s entire oeuvre.) It is very different from the herky-jerky, rapid-fire, cut-and-paste style of the rest of the film.

“The Other Side of the Wind” comes to us as a kind of time capsule of an era when Hollywood, for a brief time, opened its doors wide to creative risk. It never did welcome Welles, though, and this last, bewilderingly hectic movie from him can best be viewed, I think, not so much as a high achievement in its own right as an indictment of Hollywood’s criminal neglect. Grade: B+ (This movie is rated R for sexual content, graphic nudity, and some language.)