Field of tie-dyed dreams: How Woodstock changed a generation

Loading...

| Bethel, N.Y.

Many Americans would dismiss the gathering as a bacchanalia in the mud – three days of drugs, nudity, subversive music, and psychedelic indulgence. But 50 years ago, Woodstock became a cultural touchstone that defined an era. A number of social protest movements of the 1960s – opposition to the Vietnam War, a push for free love and personal autonomy, a clamor for civil rights and equality – seemed to converge in that field in upstate New York.

Nowadays, the hippie is an endangered species and the idea of music as a counterculture movement doesn’t resonate with a younger generation. Yet in some ways, there are parallels between the idealism of the Woodstock generation and the so-called woke generation. Like their grandparents, the millennials and iGen display a zeal to change the world. Like their forebears, they’re willing to eschew some of the status symbol comforts they grew up with, like cars and homes.

David Crosby, a musician who performed at Woodstock, says the meaning of the festival remains with him. “Woodstock was a glimpse – a momentary glimpse – into what’s possible. Into us being able to live with each other decently and peacefully.”

Why We Wrote This

Could a gathering the size of Tulsa live peace and love – not just as a slogan, but as a palpable part of their minute-by-minute being? The answer for many was yes in a way that became indelible, a stamp upon the heart.

David Crosby’s most enduring memory of Woodstock isn’t going onstage at 3 o’clock in the morning. It isn’t the fear that Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young felt at playing their second-ever show. Nor is it the gargantuan crowd, teeming like an ant colony on a field in upstate New York. No, the first image that comes to the musician’s mind is an incident between a policeman and an attendee.

That summer of 1969, hirsute hippies such as Mr. Crosby typically viewed police with fear and suspicion. Blame the tumult of the times. During 1968, there’d been several incidents in which police had shot and wounded students and black activists. Most infamously, officers in riot gear used clubs and tear gas to disperse hundreds of protesters outside the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago. Demonstrators routinely referred to the authorities as pigs.

At Woodstock, Mr. Crosby witnessed a decidedly different act by a representative of The Man.

Why We Wrote This

Could a gathering the size of Tulsa live peace and love – not just as a slogan, but as a palpable part of their minute-by-minute being? The answer for many was yes in a way that became indelible, a stamp upon the heart.

“A girl cut her foot,” recounts Mr. Crosby. “She’s standing around on one foot, bleeding badly. And this cop, who’s just come on duty and he’s got a razor-sharp crease in his pants and his shoes are as shiny as mirrors – he is really turned out – sees her. Walks over into the mud. Gets the blood and the mud all over himself. Picks the girl up and carries her gently and sweetly to his car where he lays her on the back seat, again getting the blood and the mud all over himself and his uniform and his car. He doesn’t care. He’s taking care of the girl. And then about 14 hippies push that car out of the mud.”

After a brief pause, Mr. Crosby’s voice softens. “I thought to myself, ‘You know, that’s working,’” he says. “‘That’s a bunch of humans being good to each other.’”

Fifty years on, Mr. Crosby isn’t the only boomer wistfully recalling the seminal events of those three days. It isn’t just nostalgia for halcyon days when they had more hair. Nor is it just a celebration of great performances by iconic musicians. For the baby-boom generation, Woodstock is a cultural touchstone that defined an era. A number of social protest movements that bubbled up during the 1960s – opposition to the Vietnam War, a push for free love and personal autonomy, a clamor for civil rights and equality – seemed to converge in that field in upstate New York.

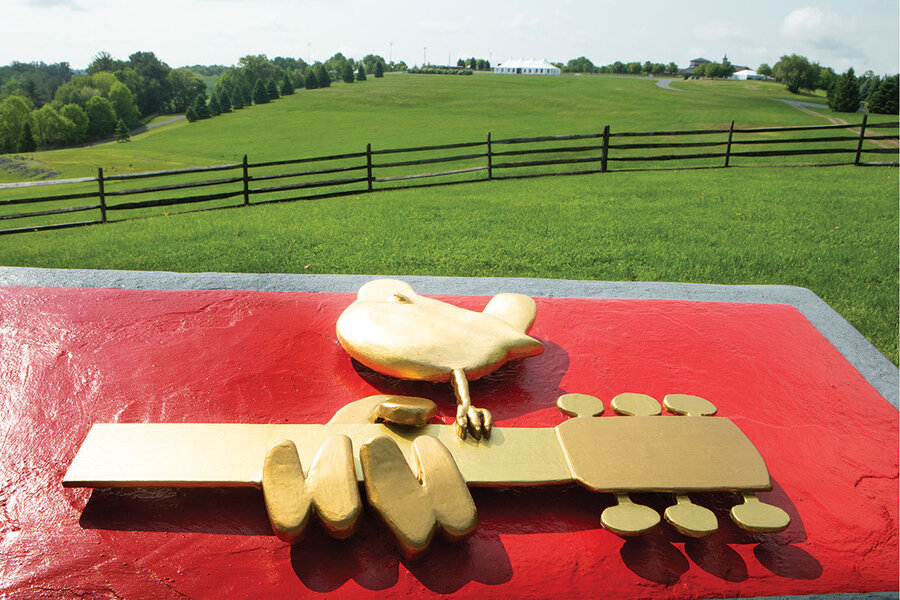

In the decades since, the festival has taken on something of a mythological status. That’s why the original site, now on the National Register of Historic Places, is the rock-music equivalent of a Civil War battlefield. Every day, visitors come from all over the world to see it. Some dress appropriately for the encounter, with tie-dye splattered across their T-shirts like melted Ben & Jerry’s ice cream.

More than a dozen books about Woodstock have been released in recent months. A big-screen documentary “Woodstock: Three Days That Defined a Generation” is scheduled to air on PBS in early August.

Today, there’s little evidence this bunny slope was once a mudslide that accommodated a stage, speaker towers, and a biblical-scale multitude. It’s now as verdant as an Irish meadow, but with a large peace sign subtly mowed in the grass. A team of archaeologists from Binghamton University, State University of New York, excavated the site earlier this year, but the only shrapnel they dug up were pull-tabs from cans.

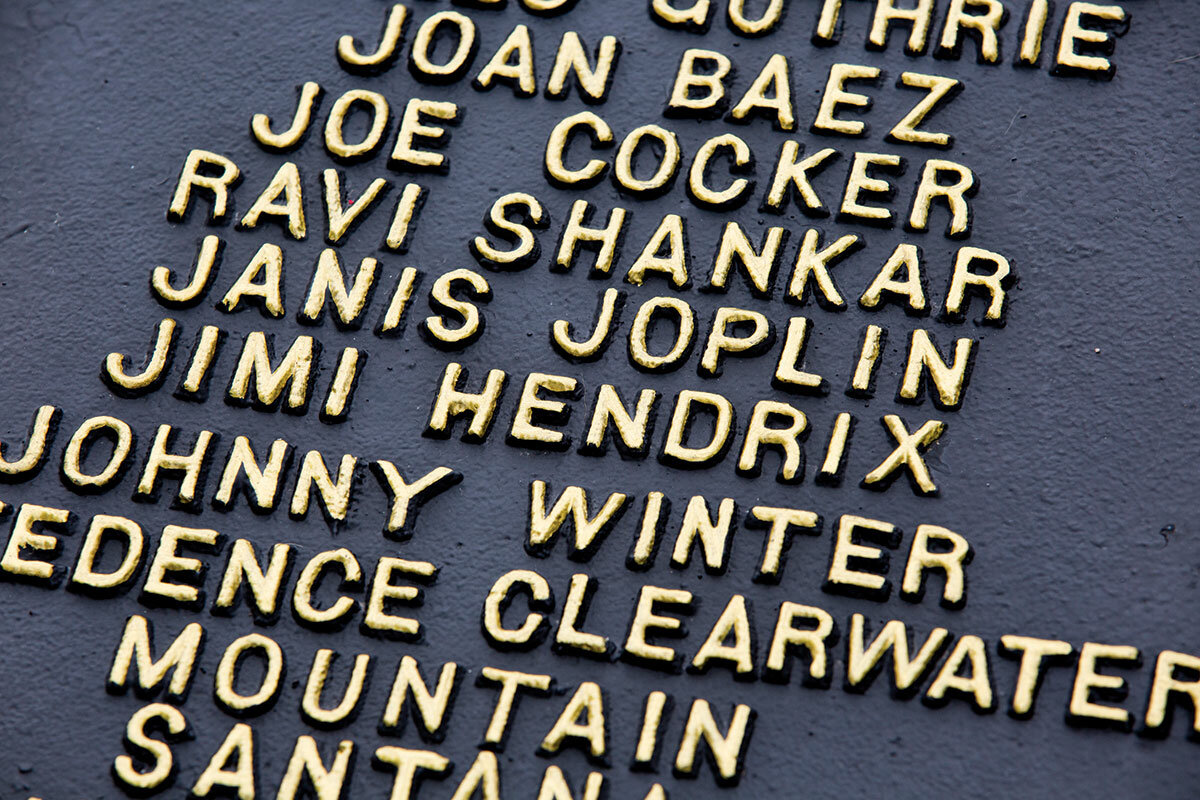

What lingers is the legacy. On one side of the field, a stone monument lists all the performers. Duke Devlin, formerly a guide at the Woodstock museum just up the road, dubs it “the Tomb of the Unknown Hippie.”

Diane Armstrong made the pilgrimage here from Snowhill, Maryland, because she missed out on the festival when she was a young teen. “There was a lot brewing back then, a lot that’s in common with what’s going on today,” says Ms. Armstrong, who feels a kinship with the people putting aside differences in a loving community. “It gives me hope. And it also makes me feel like, all those people, who are now in our political system, don’t they remember? Because they were all my age. What did they forget? Because even if they weren’t here, it was global, it was countrywide.”

Many Americans then and now, to be sure, would dismiss the gathering as a bacchanalia in the mud – three days of drugs, nudity, subversive music, and psychedelic indulgence by a lost generation of hippies and flower children. But to vast numbers of others, such as Mr. Crosby, Woodstock was an epiphanic moment of pure idealism.

Despite the challenges posed by a poorly organized music festival, the multitudes spent the weekend embodying the peace and love they espoused. To them and others who shared the spirit of the moment, Woodstock represents the apotheosis of lofty ideals that still resonate.

“This was a shift of a whole generation of people watching that phenomenon and identifying with it in some way,” says Mary VanderGoot, author of “After Freedom: How Boomers Pursued Freedom, Questioned Virtue, and Still Search for Meaning.” “It was protest music, but honestly, it was deeply optimistic in the sense there was a belief that, if you speak the truth, life will get better.”

The birth of Woodstock

To coincide with Woodstock’s 50th anniversary, event co-founder Michael Lang had wanted to stage a commemorative festival Aug. 16-18 near the original site. The lineup was to feature some performers from the gathering 50 years ago alongside newer acts such as Halsey and Chance the Rapper. (One imagines boomers asking, “Who?” And their progeny responding, “No, The Who’s not on the bill, Granddad.”) But multiple permit applications were denied, forcing Mr. Lang to consider a new venue, in Maryland. Many of the musicians, however, were uninterested in performing at a site so unoriginal from the original. Ultimately, the festival was canceled. A half-century ago, Mr. Lang faced similar travails trying to stage a concert.

In 1967, he and his cohort Artie Kornfeld, formerly a vice president of Capitol Records, set out to establish a recording studio near Woodstock, New York. They had financial backing from the heir to a pharmaceutical company and a young venture capitalist. Two years later, the four men decided to hold a music and arts festival on the site of the proposed recording studio. But locals rejected the idea. Two other venues were considered, but officials refused to issue permits. The situation was desperate. The festival had already been advertised in publications such as The New York Times. During a ride through Bethel with a local real estate agent, Mr. Lang dipped down a side road past Max Yasgur’s dairy farm and spotted the ideal venue: a bowl-shaped meadow. It was July. They only had a month to prepare the site.

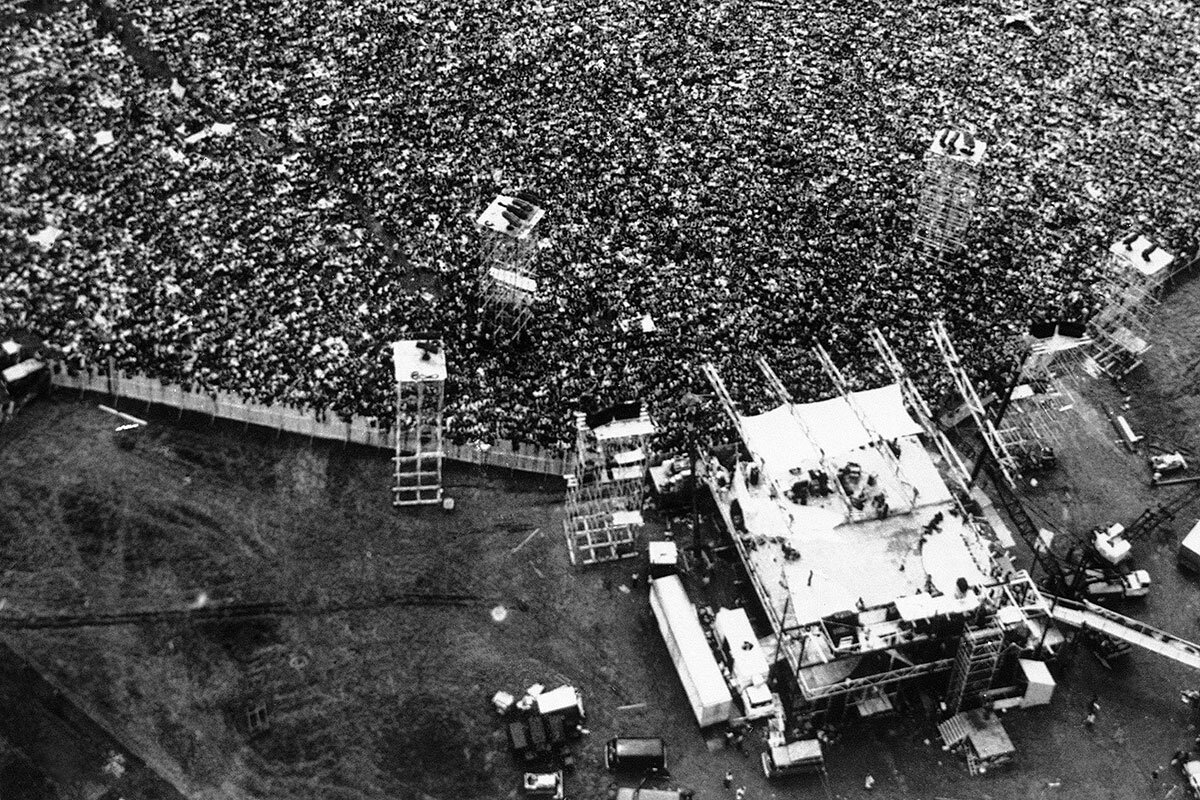

With just days to go before the event, Mr. Lang’s team faced a stark choice given their limited workers and time. They could either build the stage or erect fences and ticket booths around the festival grounds. They chose the staging. The festival had pre-sold 186,000 tickets via mail order. Without fencing, the organizers would have to let the additional people who showed up in for free. They were expecting 15,000. Their predictions were off by only 200,000. The organizers ended up going heavily into debt.

The “Aquarian Exposition,” as it was called, tapped into a counterculture movement that was sweeping the United States. Two years earlier, in 1967, Time magazine had run a cover story on hippies. The Woodstock organizers apparently didn’t read it, or if they did, weren’t aware of the number of hippies, peaceniks, rock aficionados, and others who would be drawn to a meadow in upstate New York.

“In 1965, by some estimates, there were roughly a thousand prototypical hippies living in the Bay Area,” says cultural anthropologist Grant McCracken, author of “Chief Culture Officer.” “By 1969, you’ve got a half-million people showing up for entertainment in an open field. So it’s a tremendously rapid acceleration. And I think one of the ways it gets accomplished, culturally speaking, is that people just simply define themselves in very careful opposition to the cultural model that was in place by the mid ’50s.”

That postwar period was a time of remarkable economic growth, epitomized by the rise of the suburbs and what they symbolized for material comfort and the competition for social standing. As a 1950s Ford television commercial put it: Why have one car, when you can have two? But many members of the nonconformist ’60s generation spurned status and individualistic competition in favor of egalitarianism and social solidarity.

“Spending a weekend in a muddy field seemed like a good idea, for starters, because it so affirmed the equality of all those people,” says Mr. McCracken. “Everything about the clothing and the hair was pretty deliberately an effort to efface differences.”

But what lay behind the sudden youthful attraction to Human Be-Ins (a supposedly humanistic version of the old sit-ins), Eastern mysticism, and drugs? And why did some flower children display a disregard for clothing that would make even the cast of “Hair” blush?

It was a desire for personal empowerment and expression. Earlier generations believed that if you lived in accordance with the social mores of your community, you’d be happy. But the boomers balked at that notion. First, they said, follow your bliss. Second, find a community that you fit into.

This so-called Me Generation’s redefinition of freedom included a rejection of their parents’ conservatism and the morality of the middle class. Political upheaval – the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and two Kennedys, race riots, and fear of the draft – only fueled their disaffection. They challenged authority, agitated for civil rights and women’s rights, and embraced sexual liberation. At the time, the most potent messengers for change were musicians.

A slapdash start – with heart

On a spring morning, Donny York surveys the field where his group, Sha Na Na, played just prior to Jimi Hendrix 50 years ago. The revivalists of 1950s doo-wop rock ’n’ roll have returned for a Woodstock commemorative show at the Bethel Woods Center for the Arts. They were unknowns the first time around. The festival and a subsequent documentary movie turned them into stars.

“My helicopter landed maybe between here and the stage,” recalls Mr. York, whose “West Side Story” garb, a leather jacket and rolled-up jeans, looks as anachronistic now as it did in 1969. “I’d never seen so many people in one place.”

The backcountry roads were jammed with cars and minibuses muraled with flowers. When Bob Mulvey arrived, he was dangerously hanging out the open back of a U-Haul truck that he and some friends had stuffed with mattresses. Most festivalgoers arrived far less prepared. “We had a bunch of food in the truck, so we gave away some,” says Mr. Mulvey, now a teacher at the Berklee College of Music in Boston.

Conditions deteriorated. First, food vendor supplies ran out. Then, their booths collapsed as a storm produced the worst mud since the Battle of Passchendaele. Upon hearing about the shortages, locals collected food donations (including 10,000 sandwiches) and airlifted them into the festival’s makeshift kitchens. Thousands of cups of granola were passed from hand to hand to those crammed near the stage.

“They had sort of a free food setup, which was really interesting,” says Mr. Mulvey. “I remember sitting down with just this huge group of people that we didn’t know ... and sharing food and laughing and joking about the size of the crowd.”

Sha Na Na’s Jocko Marcellino recalls venturing out among the masses because the artist hospitality pavilion had been turned into a medical station. At the top of the hill, he watched Creedence Clearwater Revival play “Born on the Bayou.” The band looked microscopic but the stage lights reflected off the drummer’s cymbals as shimmering halo rings.

“It really was a great weekend of cooperation,” says Mr. Marcellino. “And that spirit made it so special that there wasn’t anybody fighting; there wasn’t anybody burning things. People took care of each other and it gave an important spiritual background to it.”

The good vibes emanated from the stage, starting with the acoustic guitar-oriented lineup on Friday night.

“Most folk acts were protest acts. I’m thinking obviously of Joan Baez, who was the headliner for that day, and Arlo Guthrie, the son of Woody Guthrie, and obviously very politically committed,” says Julien Bitoun, author of “The Story of Woodstock Live.” “There was the ‘Fixin’ to Die Rag’ by Country Joe McDonald with the ‘One, two, three / What are we fighting for? / Don’t ask me, I don’t give a damn / Next stop is Vietnam,’ with the whole crowd chanting.”

The greatest protest song of the festival was entirely wordless. Hendrix’s instrumental version of the “Star-Spangled Banner” made the strings of his upside-down Stratocaster howl in distorted anguish. It was the aural equivalent of a flag-burning. The performance helped to establish the festival’s legendary status, says Mr. Bitoun. A few songs later, Woodstock was over.

“That community was sort of engendered in that moment, and then dissipated afterwards,” says Jefferson Airplane guitarist Jorma Kaukonen. “That’s the kind of thing you can’t really put into words or planning. All these people showed up, all this stuff happened, and they were sort of like a little Woodstock city for three days. And then it was gone. That’s the magic to me.”

An enduring mythology

Mr. Mulvey remembers arriving home from Woodstock with his pants covered in dried mud. His father, who was pretty liberal, looked at him and shook his head. But for the young aspiring musician, those three days forged a shared cultural identity.

“Woodstock is sort of a pinnacle of that sort of value system being created and understanding that there were many, many others like me,” he says. “If there were half a million people there, that probably meant that another half a million couldn’t get there. Which means it was a million people who kind of shared those values ... and probably even more than that.”

The mythology of Woodstock began almost immediately. Joni Mitchell, who didn’t attend, wrote the famous song about it. The central refrain, “We’ve got to get ourselves back to the garden,” conjured up images of festivalgoers dwelling in Edenic serenity.

It reinforced a narrative of Woodstock fitting into the centuries-old American impulse to create a utopian society, however briefly, as evidenced by the Shakers, transcendentalists, and others in early New England.

Yet within months, those utopian ideals suddenly seemed far more difficult to attain. In December of 1969, Mr. Lang’s attempt to mount a “Woodstock West” at Altamont Speedway in California was marred by the death of an 18-year-old at the hands of a Hells Angels security team.

The turn of the decade also brought fresh challenges for the boomer generation. “Almost as soon as people had decamped from that farm in Woodstock, the economy started souring,” says Joseph Sternberg, author of “The Theft of a Decade: How the Baby Boomers Stole the Millennials’ Economic Future.” “I mean you got into the oil crises of the ’70s. The culminating fiasco of that era was the stagflation of the late ’70s and then the deep recession in the early ’80s.”

Mr. Sternberg says a defining characteristic of boomers is that they’re always chasing the economic security that they grew up with in their childhoods. Only a slice of that generation identified as hippies, but many of them swapped their caftans for suits and ties. The generation’s politics, too, shifted, with many later voting for Ronald Reagan.

Now, in their twilight years, boomers are assessing their place in the world. Ms. VanderGoot says many of her contemporaries are gentle activists, no longer as strident as they once were, yet keenly involved in their communities and politics.

“You get kind of a split between people who became more pragmatic about their idealism, but are still idealists, and then there are people who kind of gave in and said, ‘Hey, you know, I had a good run at it. I did what I could but now I just want to have a comfortable life as I coast through a few more decades.’”

She believes her generation still has spiritual impulses that challenge a proclivity to seek refuge in middle-class comforts. “They carried forward those deep values, the sense that life can’t just be purely material and be satisfying,” says Ms. VanderGoot. “We know that we won’t always be around. We want to believe that there’s more than just us.”

Nowadays, the hippie is an endangered species seldom spotted outside its natural habitat of Phish concerts. But Mr. Mulvey says some of his Berklee students, fascinated to discover he attended Woodstock, are curious about his generation’s values. His students often tell him that the hippies of the time had more things to protest. His rejoinder to them is that the issues of civil rights, war, gay rights, women’s rights, and the environment haven’t gone away. Progress has been made. But there’s still work to be done. Yet the idea of music as a counterculture movement doesn’t resonate with a younger generation.

“Music has changed somewhat in terms of its importance to the students I work with,” he says. “Music is a commodity as much as it is an art form.”

Mr. Kaukonen of Jefferson Airplane, who has a 12-year-old daughter and a 21-year-old son, wishes that today’s young musicians were inspired to write protest songs like his generation did. “It’s just a different world. I think the issues today are not as clear cut,” says Mr. Kaukonen, still an in-demand recording and touring songwriter. “The issues were so clear cut back then. There was really very little gray area between what you believed in and what you didn’t. And the music and the writing and the graphic art ... that were done by the people of that generation were inextricably intertwined with the current events of the time.”

Yet in some ways, there are parallels between the idealism of the Woodstock generation and the so-called woke generation. Like their grandparents, the millennials and iGen display a zeal to change the world. Like their forebears, they’re willing to eschew some of the status symbol comforts they grew up with, like cars and homes. They’re giving up security, says Ms. VanderGoot, because they’re saying, “I’m willing to pay the price, but I hope the future will be different.”

“A glimpse into what’s possible”

Most days, Mr. Devlin drives over to the shaded Woodstock monument in Bethel. He loves to listen to the conversations of all the visitors. On occasion he might share memories such as how he, as a museum guide, once drove Mr. Crosby in a golf cart to see the site.

“I parked right on the stage and I turned the cart around, pointed up the hill and I said, ‘David this is what you saw back in ’69, without people,’” says Mr. Devlin. “He looked and he was amazed and he says, ‘You know what, Duke? The vibe is still here.’”

In a telephone call, Mr. Crosby says the meaning of the festival remains with him. “Woodstock was a glimpse – a momentary glimpse – into what’s possible. Into us being able to live with each other decently and peacefully. It showed you what it could be. [That] we can do it.”