A witness in Galilee

Loading...

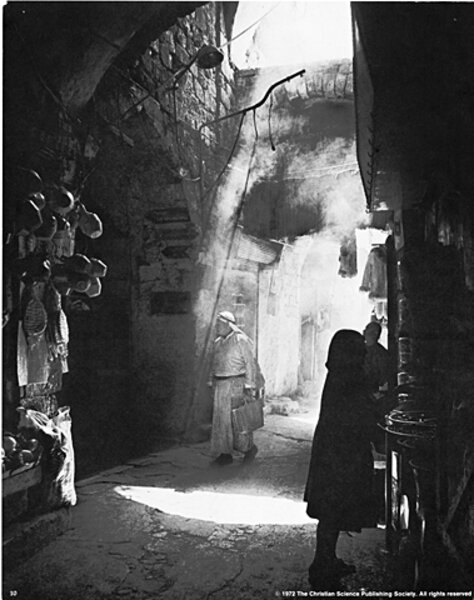

In Jerusalem, where the conflict between Jews and Muslims dominates everything from religion to politics, it can sometimes feel as if Jesus of Nazareth and all that he stood for has been forgotten here – or at least cast aside.

Christians today make up only 2 percent of Jerusalem's population, and despite Jesus' connection to this land and many of its sites, there is little mention of the man whose ministry inspired the world's largest religion. Even when referring to his followers, Israeli Jews emphasize geography rather than good works. In Hebrew, Christians are notzrit – someone from Nazareth.

So when I heard that a young Israeli and his American hiking buddy had audaciously named a walking route the Jesus Trail, I set off for the fields of Galilee with a backpack and a Bible.

I had no illusions that roving through the pastoral landscape where Jesus led his little flock would make me more of a Christian, but I did want to peek into his classroom.

Like others weaned on the Word in far-off Sunday schools, I was familiar with the names – Nazareth, Cana, Capernaum. While I have long cherished the ideas Jesus imparted, it wasn't until I came here that I appreciated more fully the context in which he carried out his three-year ministry – and how much compassion, forgiveness, and courage it must have required.

When Jesus "went up into a mountain" to deliver the sermon that is now the cornerstone of Christianity, some say he came to the Horns of Hittin.

With its wide views of the Sea of Galilee, this windswept knoll lies halfway along the Jesus Trail, between the hills of Nazareth and Capernaum.

In the field between the rocky "horns," there would have been plenty of room to sit and hear Jesus speak. Perhaps then, as now, the grassy saddle was studded with gnarled olive trees whispering in the breeze, cooling the sweaty brows of those hungering and thirsting after righteousness.

It was from the edges of the Galilee, and often the fringes of society, that Jesus drew his followers – fishermen, farmers, a tax collector. Rereading his parables, I am struck with how thoughtful he was in using metaphors from the daily lives of such simple folk.

Someone who farmed these verdant valleys or coaxed a few grapes off the vine while tending sheep would easily grasp his parable about spotting false prophets. "Ye shall know them by their fruits," he said. "Do men gather grapes of thorns, or figs of thistles?" Anyone who has bitten into the soft, sweet flesh of a perfectly ripe fig could never confuse it with the spiky thistles that punctuate the Galilean region.

The ridges of the Galilee, with their whistling pines and grassy paths, feel serene – especially compared with the religious intensity of Jerusalem. But the quiet of this undulating land belies its turbulent past. When Jesus moved his ministry to Capernaum, he was putting himself at a political junction on the Via Maris, an important trade route leading to Damascus.

Jesus encountered a centurion at Capernaum, a Roman captain in charge of 100 soldiers. I've always loved the willingness of the Roman "man of authority" to recognize and yield to Jesus' spiritual authority – who then found his paralyzed servant healed.

But here I saw a new dimension: The Romans were military occupiers. To me, that makes the centurion's humility and Jesus' compassion that much more remarkable – and food for thought in today's paradigm of occupier and occupied.

Sitting on the rocky shore at Capernaum, with the placid expanse of the inland Sea of Galilee stretching into the distance, it is easy to imagine Jesus gliding through the region healing people. But in fact he encountered strong countercurrents everywhere. Sometimes they were literal currents, as in the storm he stilled on this very lake. Other times they were mental or moral in nature. All had to be met with extraordinary courage.

Up there on the left, steep green hills plunge to the sea – the hills down which a herd of pigs ran violently into the sea during Jesus' healing of the insane Gadarene man.

To the right, grassy slopes covered in a mist of flowering mustard plants rise from the shore where Jesus patiently waited until his disheartened disciples, casting about for a new sense of purpose after his crucifixion, recognized him as their risen Savior.

As Easter dawns again on the shores of the Galilee, I return to Jerusalem with a deeper conviction that Christianity can never be snuffed out by religious strife or political tension, ignorance or prejudice. As Muslim calls to prayer ring out across the rocky hills and I pass through checkpoints manned by teenage Israeli soldiers, I resolve to bear truer witness to the redemptive power of compassion and forgiveness.