A curlicue of hope for cursive writing

Loading...

Cursive was an obligatory lesson in my day. Connecting all the letters in a word in a wobbly flow was fun for me. I was a natural.

Cursive was no longer required when my grandson entered school. But one day when Connor was about 8, he watched me pen a letter to a friend.

Why We Wrote This

Sometimes the beauty of a thing is obscured by the fact that one is obliged to learn it. It’s a joy to see a child embrace a skill that used to be required – cursive handwriting – just because they like it and it’s “weird.”

“How do you do that?” he asked, his brow furrowed. “Can I learn it?”

Sports were Connor’s passion. He hadn’t shown much interest in school except for art class, where he excelled. Library books with cursive exercises were borrowed, and Connor bent over them with a concentration normally reserved for console games.

When he turned in his first assignment written in cursive, his teacher called me up: “How did he learn that?”

Connor didn’t have to learn it. So why had he, I asked him recently. “It was just weird, different,” he said. “I wanted to do it.” It was faster than printing, too, leaving more time for sports.

Cursive is old-school. But as an object of study, it wouldn’t be out of place in art class, in history class, or even in the free-flowing quiet of a desktop – an actual desktop – at home.

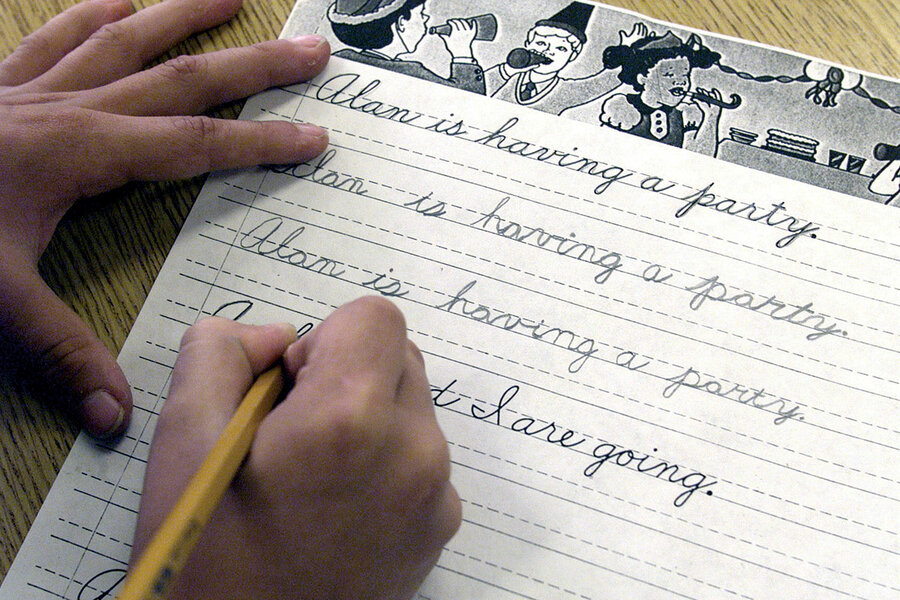

I can still see and feel the sheets of white, blue-lined paper on which I learned cursive writing. Cursive was an obligatory lesson of early education in my day. Connecting all the letters in a word in a wobbly flow and with my own individualistic slant struck me as excellent fun, and I was a natural. I hardly recall printing, once I’d learned to write.

Cursive was still taught when my son entered elementary school, but was no longer required by the time my grandson entered school. Computer keyboards had supplanted handwriting, and children took to them swiftly.

Grandson Connor was soon coaching me on computers’ advantages and possibilities. Cursive was old-school.

Why We Wrote This

Sometimes the beauty of a thing is obscured by the fact that one is obliged to learn it. It’s a joy to see a child embrace a skill that used to be required – cursive handwriting – just because they like it and it’s “weird.”

But one day when Connor was about 8, he watched me as I penned a letter to a friend. “How do you do that?” he asked, his brow furrowed. He might well have been puzzling over an illuminated medieval manuscript.

I was taken aback. How, indeed? I’d been taught, I said, and I’d had lots and lots of practice. “Can I learn it?” he asked.

Sports, especially soccer, were Connor’s passions. While he did enjoy school, he hadn’t shown much interest in anything but art class, where he excelled.

Art class was an ideal launch point: He was already into the creative flow of a pencil or crayon on paper. Library books with cursive exercises were still to be had, and he began bending over them with a concentration normally reserved for console games and Pokémon cards.

When he turned in his first school assignment written in cursive, his teacher called me up: “How did he learn that?”

To me, learning cursive is like learning to pedal a bike or glide into turns on skis. Once you have it down, it’s a lasting skill.

Connor saw cursive as a compelling new art form. He didn’t have to learn it, which may have helped to open his portal of interest. When I asked him recently what he remembered about his boyhood fascination with cursive, he said, in his laconic way: “It was just weird, different. ... I wanted to do it.”

I didn’t recall which teacher had commented on his first cursive paper – and neither did he, because “so many of them said I had really nice handwriting.” He didn’t do it to impress. He did it because he wanted to.

Connor persisted. He evolved his own handwriting style and flow. He also found that cursive was faster than printing: It saved him time for things like soccer. Printing was to cursive what tiptoeing across a frozen pond is to ice-skating. He was hooked, and he continued to invent and embellish his script.

Cursive may not be integral to school curricula any longer. We are where we are, now, in the arc of human communication. But I hope cursive handwriting continues to attract and engage children, at least some of them, the way it did my grandson – with no more prompting than seeing someone use it to fill a sheet of paper with news for a friend.

As an object of study, script writing wouldn’t be out of place in an art class, in a history class, or even in the free-flowing quiet of a desktop – an actual desktop – at home.