Build your vocabulary the novel way

Loading...

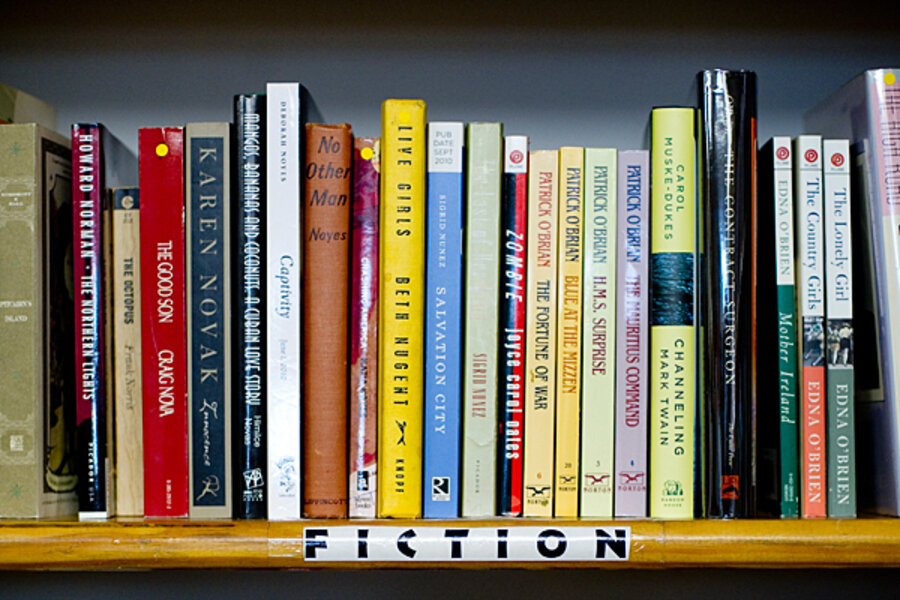

A year after my household move, I still don't have my library organized. Far too many books have my place marked with a sticky note, or just a slip of paper, from the days before there even were sticky notes. Disproportionately fiction, these books seem like inadvertently neglected friends.

New research makes me feel even worse about this. It shows that the biggest vocabularies belong to those who read "lots," and in particular, read "lots" of fiction.

These findings come from the website Testyourvocab.com, described as "part of an independent American-Brazilian research project to measure vocabulary sizes according to age and education."

The site lets you measure your own vocabulary via a quick self-test, a sort of watermelon-core sample of word power. One page measures your "broad" vocabulary level: You review a set of words and check off those for which you know at least one meaning. This page is fairly easy, although uxoricide has turned up several times as I've tried it.

The second page, apparently cued to your answers on the first, uses the same method to test for a narrower vocabulary level. The third page asks about native-speaker status, education, and the like. Then with one click, you get an estimate of your total vocabulary. (The Oxford English Dictionary lists 300,000 words.)

It is entirely possible to cheat here, and even if people are trying to play fair, they may check a word whose meaning they only think they know. Also, a self-selection bias is at work.

But the aggregated results from over a quarter-million self-selectors have led to some conclusions worth sharing: Adult native test-takers have vocabularies ranging from 20,000 to 35,000 words, but even the average 8-year-old has a vocabulary of 10,000 words, and a 4-year-old knows 5,000. People of all ages keep learning: Young people (ages 4 to 15) who read a lot pick up more than four new words a day. Even adults pick up an average of nearly a word a day until middle age.

And this: "[W]hile increasing your reading matters, increasing your reading of fiction, specifically, matters equally as much. That fiction reading would increase vocabulary size more than just non-fiction was one of our hypotheses – it makes sense, after all, considering that fiction tends to use a greater variety of words than non-fiction does. However, we hadn't expected its effect to be this prominent."

It may be obvious, but it's still worth noting. A novelist, knowing that her readers are with her and her story by choice, can use a richer vocabulary than a textbook author who must write to a given grade level for readers who read only because they must.

Consider the difference between the knowledge you acquire by immersion and the knowledge you acquire by marching, or being marched, through a list of what educators call "learning objectives." Think, for instance, of the way you learn the streets of the place where you live: one by one, over time, quite literally "in passing."

A fiction writer has the time to find the perfect word in a way that a journalist or other more time-constrained scribe may not: the exact right word, not the almost-right one that will fit in the space or take some fraction of a second less to say aloud. And a fiction reader has the time to absorb those exact right words – and is rewarded thereby with a richer vocabulary.