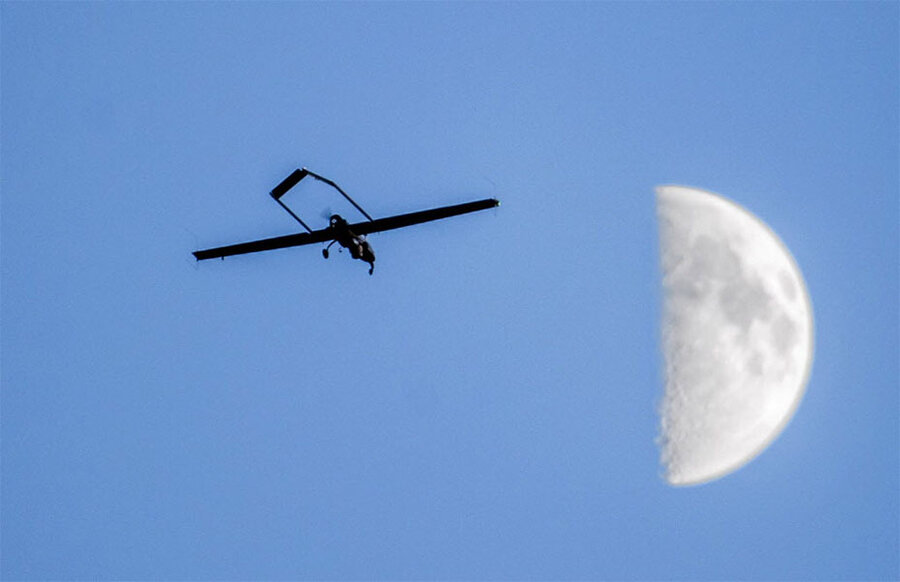

Droning on about those things in the sky

Loading...

I have mixed feelings about drones.

But I’m pleased that drone, and not some goofy spoonful of alphabet soup, seems to have emerged as the preferred term for unmanned aircraft.

Thus The Washington Post reported Oct. 19, “Federal regulators said Monday that they will require recreational drone users to register their aircraft with the government for the first time....”

It’s heartening when a term for a new thing is not just initials or some bit of jargon but an actual word – whether cobbled together from parts lying around the vocabulary workshop, as when television was coined from Greek words meaning “far seeing,” or borrowed on the basis of a sensible analogy from some other realm, as when the nautical pilot was adapted for aviation. An imaginative neologism can be a thing of beauty.

However, unmanned aerial vehicle, abbreviated to UAV, is the more formal term for drones, often preferred by military types. Drone is from an Old English word meaning “male honeybee,” according to the Online Etymology Dictionary. The word’s origin is “probably imitative” – the word echoes the sound the critters make.

A drone has no sting and produces no honey. By the 1520s, drone had a figurative sense of “idler, lazy worker,” the etymology dictionary notes. P.G. Wodehouse played on this sense in his 1940 story collection, “Eggs, Beans and Crumpets.” The Oxford English Dictionary quotes: “In the heart of London’s clubland there stands a tall and grimly forbidding edifice known to taxi-drivers and the elegant young men who frequent its precincts as the Drones Club.”

It all sounds like fun, but another use of drone made its way into print soon after. The Online Etymology Dictionary quotes Popular Science in 1946: “Drones, as the radio-controlled craft are called, have many potentialities, civilian and military. Some day huge mother ships may guide fleets of long-distance, cargo-carrying airplanes across continents and oceans.”

If the beehive analogy were more complete, however, drone aircraft might be those that carry no bombs or other payload, rather than those that carry no pilot. So how do we get to drone?

In the 1930s, a time of great technical advancement in attack aircraft, the British Royal Navy wanted to test its air defenses. Hundreds of old de Havilland biplanes were rigged up with remote controls for Navy gunners to practice shooting at. But in fact the Queen Bees, as these aircraft were known, served to identify holes in British air defenses.

A visiting American admiral saw a Bee in action and decided the United States needed something like it. And so when Delmer Fahrney, the officer put in charge of the American effort, came up with the US Navy’s first unmanned aircraft, he called it a drone “in homage to the Queen Bee,” historian Steven Zaloga has written. Ben Zimmer noted in a Wall Street Journal piece a couple of years ago, “The term fit, as a drone could only function when controlled by an operator on the ground or in a ‘mother’ plane.”

Now “unmanned aerial vehicle” just doesn’t tell that kind of story, does it?