NASA heads back to the moon

Nearly 5-1/2 years after former President Bush decided to send US astronauts back to the moon by 2020, America is set to launch the first mission supporting that goal.

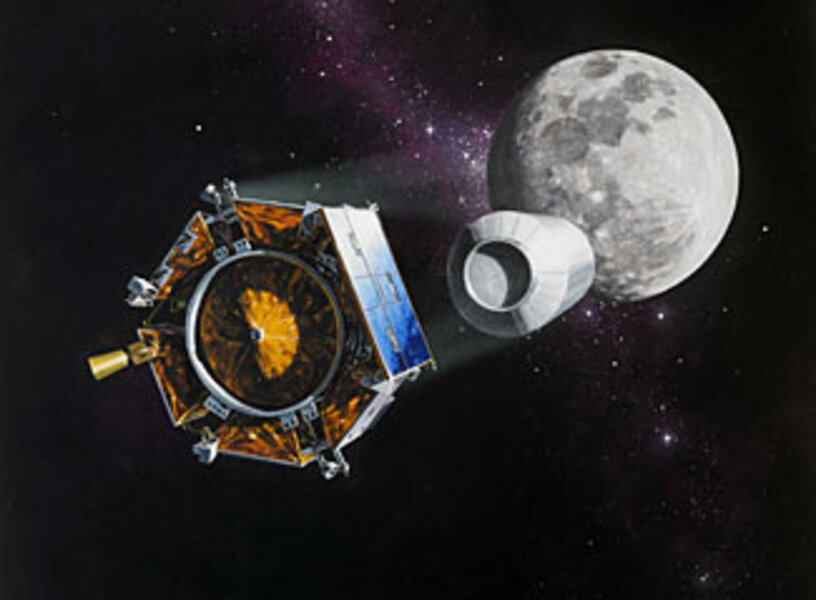

The Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) and a companion spacecraft are set for launch Thursday aboard an Atlas 5 rocket. The $504-million mission is scheduled to take off as early as 5:12 p.m. Eastern Standard Time.

After a four-day journey, and another 66 days of testing and easing the spacecraft into its final orbit, the LRO will circle the moon some 31 miles above its surface, building the most detailed atlas yet of Earth's companion. The data will help planners figure out where to send astronauts when it's time to put boots back on the lunar surface.

After the first year, the orbiter will continue working for an additional year or two with emphasis on answering basic questions about the moon – about the composition of the moon's "seas" and highlands, and its geologic history written in the rocks exposed in crater walls.

"This is exploration and science working together," says Mike Wargo, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration's (NASA) chief lunar scientist.

The orbiter will gather images of objects as small as 18 inches across, build contour maps of the lunar surface accurate to within about three feet, and map surface temperatures at different latitudes and through the moon's subtle seasonal changes. It will gather information on radiation hazards from the sun, from cosmic rays from deep space, and from energetic neutrons those rays kick up when they strike the lunar surface. It will also map the distribution of surface minerals.

From the standpoint of establishing lunar outposts, a key task is hunting for water ice that may lurk in the permanent, frigid darkness at the bottom of craters at the moon's poles. Past spacecraft have yielded evidence of water. But the signs have been vague.

That's why the mission includes some fall fireworks. In October, the orbiter's companion craft, the Lunar Crater Observing and Sensing Satellite (LCROSS), is destined for a lunar smack-down. The craft – actually a guidance-and-instrument package mated to the Atlas rocket's upper stage – will steer the stage toward a head-on collision with the bottom of a polar crater. One NASA scientist has likened it to a VW bug pushing a school bus.

At the right moment, the package will release the spent upper stage and follow it down, measuring the results as the collision kicks material from the dark crater floor back into sunlight. Scientists say they expect the plume to extend to some four miles above the crater rim. Shortly after the upper stage augers in, the guidance package also will end up as rubble on the crater's floor.

"This is the crescendo event," says Dan Andrews, the project manager for LCROSS.

Space-based telescopes, the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter, India's lunar orbiter, and several ground-base observatories will try to tease out the material's composition with an eye toward capturing the signatures of water ice, if it's there. The event also is likely to be visible to amateur astronomers with the right-sized telescope.