Free 40,000 California inmates? Not so fast.

Loading...

| San Francisco

Is California about to open its prison gates, freeing more than 40,000 inmates?

Earlier this week, a federal judicial panel gave the state 45 days to come up with a plan to cut its prison population in order to adequately care for its inmates.

But don't expect inmates to be freed from any of California's 33 adult prisons next month. Even if prison officials come up with a plan that both lawmakers and the federal court justices accept, the state would have two years to carry out any reduction.

If the court does actually mandate a release, the state would appeal that ruling to the US Supreme Court. Right now, state lawyers are still reviewing the justices' 184-page decision that was issued Tuesday.

"All the court has asked for in this ruling is for the state to develop a plan in 45 days … so the legal question is whether or not the state can appeal a ruling that directs us to come up with a plan," says Seth Unger, press secretary for the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation.

Unconstitutional overcrowding?

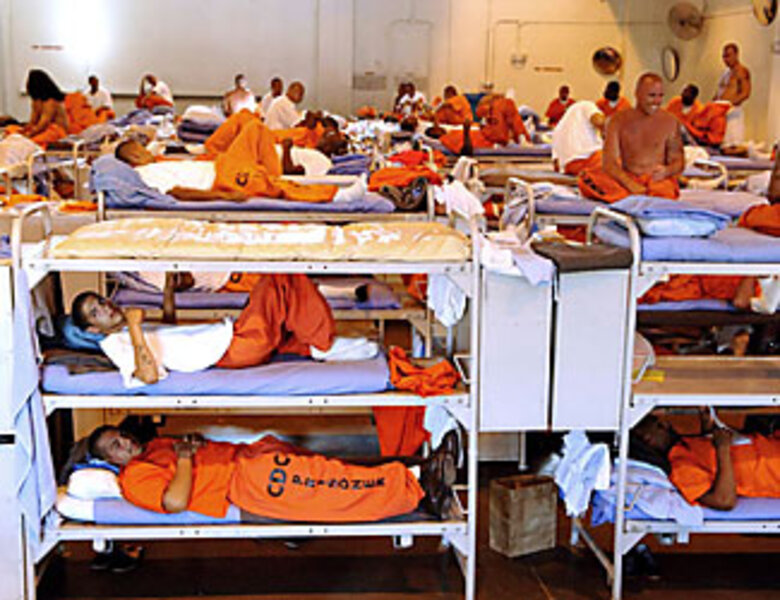

At issue in the court case is whether overcrowding in California's prisons has resulted in an unconstitutional level of care for the state's 155,000 inmates (12,000 of the state's inmates are housed in other facilities or in out-of-state prisons).

"The medical and mental healthcare available to inmates in the California prison system is woefully and constitutionally inadequate, and has been for more than a decade," said the judicial panel in their ruling this week. "California's prisons are busting at the seams and are impossible to manage."

The judges want to see a reduction in population to "137.5 percent of the adult institutions' total design capacity."

Prison population is now at 195 percent of capacity, according to Mr. Unger. "But design capacity can be somewhat misleading. Capacity is based on one inmate per cell…. You can put two inmates in a cell and have them safely housed," he says.

The Prison Law Office, based in Berkeley, Calif., brought the original lawsuit that resulted in Tuesday's decision. It claimed that the overcrowded conditions were so bad as to be a violation of the Eighth Amendment, which outlaws cruel and unusual punishment.

"The Constitutional standard," says Donald Specter, director of the law center, "is that the prison can't be deliberately indifferent to the prisoner's medical needs."

Prisons have improved over the past several years, he says, but "you have to understand that we are talking about a system where you couldn't even see a doctor. And there are still not enough doctors. Is it Constitutional? No."

State proposes

The state government doesn't dispute that prisons are overcrowded – Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger declared an emergency over the issue in October 2006. But California Corrections Secretary Matthew Cate says the justices overstepped their authority in forcing the state to come up with a plan.

Mr. Specter counters that the court's decision is not unprecedented. "There is a long tradition of the federal courts … intervening in prisoner affairs because the state judicial system is insufficient in protecting prisons' human rights," he says.

Independent of this week's court order, the state has already proposed several ideas for lawmakers to ponder. These proposed measures could result in a reduction of some 27,000 inmates and save the state $1.2 billion in one year:

•Allow low-risk offenders to serve the remaining year of their sentence under house arrest.

•Limit parole supervision only to offenders who committed serious or violent crimes to reduce recidivism caused by parole violations.

•Reform sentencing guidelines for crimes associated with property theft and raise the threshold from $400 to $2,500.

•Give inmates the chance to receive credits toward their sentence if they participate in certain behavioral, educational, or rehabilitation programs.

Specter says he approves of many of these measures, but it remains to be seen whether lawmakers will also approve. It can be politically risky for politicians to vote for programs that shorten sentences or result in inmates being released from prison.

That leaves the "federal courts as the only one to solve the problem" in California, he argues.