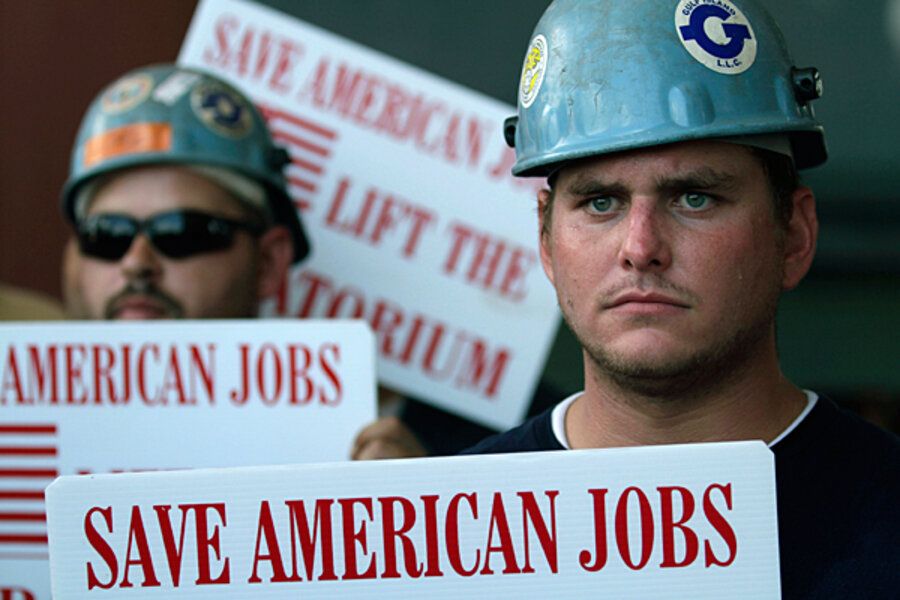

Gulf oil spill aftermath: Will region regain lost jobs?

Loading...

Even as the oil industry in the Gulf of Mexico looks to the Nov. 30 expiration of the federal moratorium on deepwater drilling, economists are warning that conditions may not be favorable for oil companies to restore the thousands of jobs lost to the measures that were imposed after the Deepwater Horizon oil rig exploded in late April, killing 11 workers.

The warnings are being issued amid sharp disagreement between the oil industry and its critics over the longterm impact of the moratorium on employment in the Gulf region.

A report issued by the US Department of the Interior last week that significantly lowers job loss projections swiftly came under attack by those who say its assessment does not present a realistic picture of the federal moratorium’s long-term impact.

IN PICTURES: Louisiana oil spill

In late May the Obama administration suspended oil drilling in water depths greater than 500 feet for six months so it could review safety measures related to the deadly explosion of the Deepwater Horizon, which also released an estimated 205 million gallons of oil into the Gulf of Mexico.

But what is becoming a matter of debate is how much the six-month halt in operations will affect the region’s long-term employment as oil companies may consider moving to foreign waters, where regulations governing exploration and production are likely to be less onerous than what is expected to result from the current inspection process.

Additionally, some economists say the region may be impacted by mass lay-offs starting at the end of this year when companies react to a number of factors: unstable natural gas and oil prices, revenue losses resulting from the last six months, and a new regulation framework, the impact of which is expected to significantly shake up the economics of the area even if the details are not yet known.

According to Michelle Foss, chief energy economist at the Bureau of Economic Geology at the University of Houston, oil companies are facing “a lot of open-ended risk,” especially at the end of the year when drilling leases and contracts are up for renewal.

“There are enormous issues that need to be resolved and that’s not going to happen in two months, especially when no one knows where they stand right now,” Ms. Foss says.

Despite the uncertainty, the Interior Department report revised what it originally predicted would be 23,000 jobs lost due to the moratorium to a job loss between 8,000 and 12,000. The report says a primary reason for the revision is that the mass layoffs predicted as a short term impact of the moratorium did not materialize. Instead, the majority of oil companies maintained payrolls by redirecting workers to perform repairs or other jobs not related to drilling. The report called the losses temporary and added that “most [jobs] would return following the resumption of deepwater drilling” in the Gulf.

Louisiana Governor Bobby Jindal, in a statement released last week, described the Interior Department findings as “disconnected from reality” and said some companies are “actively exploring additional opportunities to relocate rigs as the moratorium continues.” Of the 33 companies engaging in deepwater drilling in the Gulf at the time of the moratorium, three have relocated their operations to Nigeria, Egypt and the Condo.

The agency report also minimizes job losses by analyzing unemployment claims in Louisiana, Mississippi, and Texas. Of the over 300,000 total claims in those three states from early May through Sept. 13, only 820 were directly related to the moratorium, the report states.

Joseph Mason, an economist in the department of finance at Louisiana State University in Baton Rouge, says unemployment claims data do not present a realistic snapshot of the moratorium’s impact. Mr. Mason says rig workers who got hired by BP on cleanup crews or joined commercial fishing boats were not eligible for unemployment benefits and therefore would not be counted.

“With the actual job situation, you have a variety of conflicting policies so it’s difficult to say what [is] the actual number that you should see,” he says. A report he authored in August concluded that about 20,000 jobs were lost, both in the region and nationally, because of the moratorium. His report was sponsored by the American Energy Alliance, an oil industry advocacy group, leading environmental groups to allege the report was biased, but Mason says his estimates could have been much higher.

“As an economist I’m a tenured professor and I have nothing to gain. My only point is to convey a simple message: if you take away economic production, that will have an implication on economic growth overall,” he says.

Foss calls any estimation on job losses “premature” because of the uncertainties connected to the moratorium’s outcome. “They are tying to estimate economic impacts for something that is pretty much a moving target,” she says.

While job losses on the oil rigs are certain, she says, a greater number of white-collar jobs such as lawyers, accountants and engineers are in the industry crosshairs, which will have “a much bigger impact.”