An earthquake in Indiana? How does that happen?

Loading...

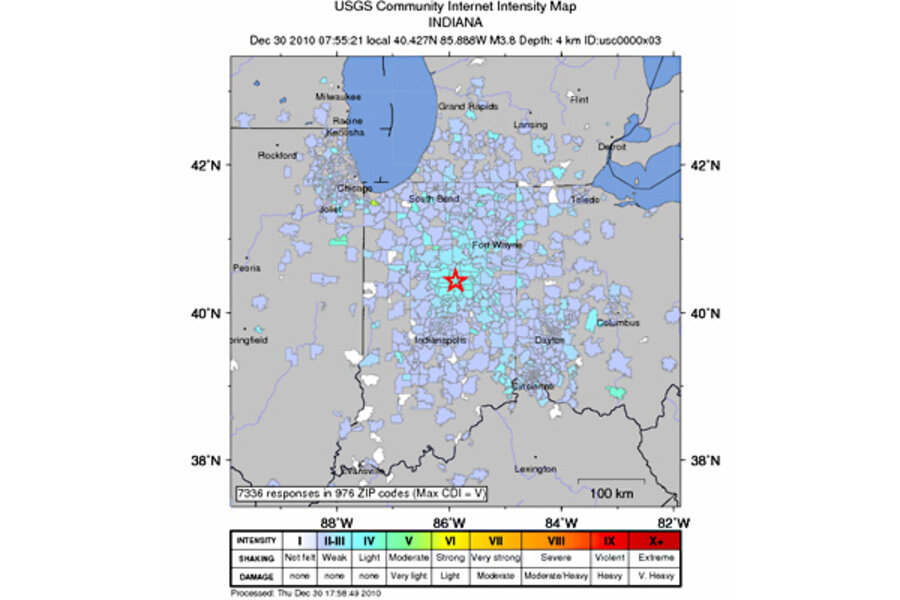

The magnitude 3.8 earthquake in Indiana this morning came as a surprise to many people, including geologists.

“This is an area that’s had very little seismic activity, even looking at the historical record,” says Michael Hamburger, program director of the Princeton Earth Physics Project at Indiana University. “It’s a little bit of a surprise.”

This region “is one of the quietest areas in this part of the country,” says Dr. Hamburger. The best-known Midwestern earthquakes come from the New Madrid Seismic Zone, located well south and west of this quake.

Earthquakes happen every day, but the vast majority are concentrated along the boundaries between tectonic plates. But since Indiana is about as far as you can get from any plate boundary – the nearest ones are at the California coast, the mid-Atlantic, and the Gulf of Mexico – what gives?

Though far from any boundary, this quake was probably triggered by plate movement, says Hamburger. “The motion was typical of earthquakes in this part of the country – compression – as though the continent is being squashed together from east to west,” he explains.

One hypothesis is that the earthquake is related to a push from the Mid-Atlantic Ridge – the spreading zone beneath the Atlantic that is pushing Europe and America farther apart and shoving North America against the Pacific plate.

An earthquake of this magnitude happens "once every year or so somewhere in the Midwest, most commonly down in the New Madrid Seismic Zone or Wabash valley." The lower the magnitude, the more common. "A magnitude 3.0 earthquake happens about 10 times each year – once every month or couple months. They tend to happen at the small magnitudes pretty frequently, but in this area it’s very rare."

The last rumble felt in the area was in April 2008, when a magnitude 5.4 earthquake near Mount Carmel, Ill., shook much of the eastern half of the country.

The immediate report for Thursday’s quake estimated the depth of this strike-slip earthquake as three miles below the surface, which is relatively shallow. “There’s another estimate that places it much deeper, about 14 kilometers [nine miles],” says Hamburger. “The jury’s still out on how deep it is. We may have a revised depth estimate before the day is over.”