Nuclear reactor crisis: Is radiation a threat to US?

Loading...

| Washington

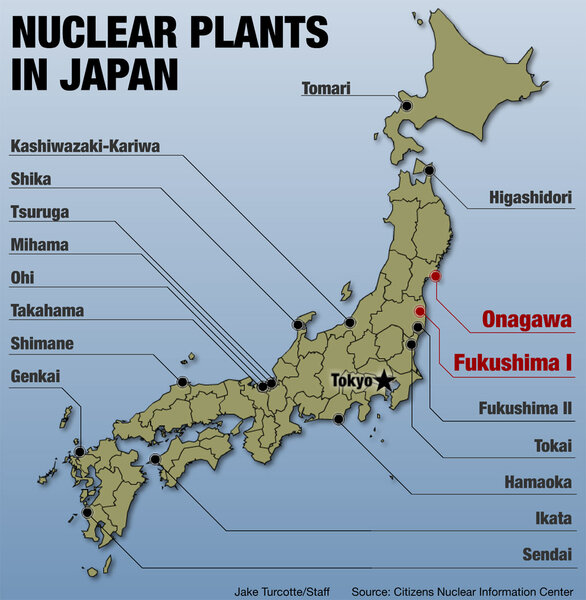

The nuclear situation in Japan certainly sounds harrowing. Authorities are struggling to prevent meltdowns at a number of reactors. Water levels dropped sharply Monday inside at least one nuclear reactor, twice leaving uranium fuel rods exposed to the air, raising the meltdown threat.

Meanwhile, the US Navy’s Seventh Fleet has moved its ships and aircraft farther away from the stricken nuclear plants after onboard instruments detected low-level radioactive contamination.

Beyond concerns for people in the immediate area, does this mean that a radioactive cloud is now drifting toward the US mainland?

No, it does not. Release of radioactivity from the reactors has been limited so far, according to Japanese authorities. The steel containment vessels remain intact, keeping dangerous materials within.

“What has happened is melting of fuel in reactor cores, leading to release of a very modest amount of cesium and other fission products,” noted Matthew Bunn, co-principal investigator of the Managing the Atom Project at Harvard’s Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, in a Monday analysis of the situation.

The crisis is far from over, of course. The situation, Mr. Bunn adds, could quickly change.

“There is a possibility of a larger release, if melted fuel falls to the bottom of the reactor and manages to burn through the containment, contacting water and creating radioactive steam,” writes Bunn.

According to US officials, the amount of radioactive material released so far does not constitute a dire threat to the United States itself. All available indications are that prevailing easterly winds have blown the small radioactivity releases from the affected reactors out to sea.

“Given the thousands of miles between the two countries, Hawaii, Alaska, the US territories and the US West Coast are not expected to experience any harmful levels of radioactivity,” said the Nuclear Regulatory Commission in a statement on Sunday.

But considering whether a cloud of dangerous radioactivity is or is not drifting over the Pacific to California may not be the best way to envision the dangers of the situation.

We’re all exposed to a certain amount of radioactivity from natural background sources. Americans old enough to have lived during the era of atmospheric nuclear tests have some amount of radioactive residue from those tests. Today, tiny amounts of radioactivity from Chinese nuclear tests can still travel to the US on the wind.

“The question is not can it reach us. The question is, in what concentration,” says Daniel Hirsch, a lecturer in nuclear policy at the University of California, Santa Cruz, and president of the Committee to Bridge the Gap, a nonprofit that works to expose what it says are the dangers of nuclear power.

Prevailing winds in Japan blow west to east, notes Mr. Hirsch. Radioactive materials released by the current crisis would take about four days to reach Alaska and another day or so to reach the continental US.

Official statements have indicated that releases of radioactivity have been modest, but it’s not really known what has been going on inside the reactor containment vessels. It appears that the plants have suffered at least partial meltdowns. The fate of used reactor fuel stored in the containment buildings in cooling ponds is unknown, Hirsch says.

“Clearly there are significant radioactivity releases already,” he says.

Any amount of radiation can have an effect, Hirsch says. Scientists say that higher levels of exposure lead to higher probabilities of disease in affected populations.

The 1986 Chernobyl nuclear disaster blew a plume of radioactivity around the world. Estimates of the additional cases of cancer this may have brought on range from 30,000 to 1 million.

Chernobyl had no containment vessel, however. Its nuclear fuel melted down and released vast amounts of contamination directly into the atmosphere. That is why the steel and concrete containment cases in Japan are so important – and why it is important that they are not breached by melting fuel rods.

• Material from the Associated Press was used in this report.