Japan nuclear crisis: Is massive water dump making any difference?

Loading...

| Washington

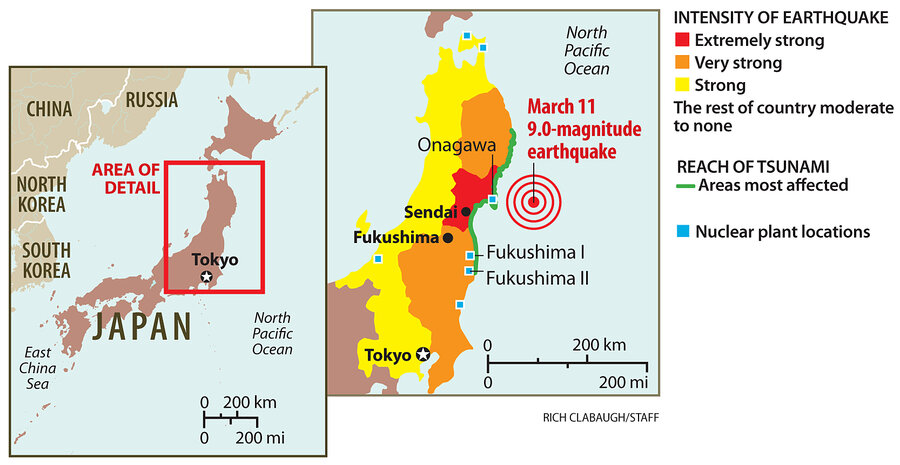

As Japan races against time to control its nuclear crisis, the cooling pools for the spent fuel rods at the Fukushima nuclear plant remain a source of major concern. On Friday water levels in at least one pool – housed in the Unit 3 reactor building – were dangerously low, according to Japanese authorities.

Japanese workers poured more than 60 tons of water into the Unit 3 building on Friday, with an as yet unknown effect, said Japanese officials.

“Dealing with Unit 3 is our utmost priority,” said Chief Cabinet Secretary Yukio Edano.

In addition, water in the Unit 4 cooling pool remained perilously close to the boiling point, at about 184 degrees Fahrenheit, according to temperature readings posted on the International Atomic Energy Agency website. Water in other pools was cooler, but readings were creeping upwards.

Japan nuclear crisis: Nuclear terminology 101

“Japan’s Nuclear and Industrial Safety Agency has reported increasing temperatures in the spent fuel ponds at Units 5 and 6 since 14 March,” noted the IAEA on Friday.

Overall the situation at Fukushima remained grave but apparently stable on Friday. Japan raised the rating of the nuclear accident from four to five on an international scale, reflecting recognition of the severity of events that have already occurred. Level four accidents have local consequences, while level fives are judged to have wider repercussions. The nuclear accident at Three Mile Island in the US was rated level five.

US officials on Friday stressed that they and the Japanese were focused equally on the damaged reactor cores as well as the spent fuel pools perched near them inside reactor buildings. The accident rating was raised at least in part because of the belief on the part of the Japanese that some exposed fuel rods inside reactors have experienced a partial meltdown.

Spent fuel rods more exposed

But the fuel pools now may pose a greater short-term danger, said experts in nuclear power. The reactors are housed within steel containment structures. The pools are just that – pools of water holding old fuel rods without any special safety equipment beyond that provided by cooling systems and the reactor buildings themselves.

Hydrogen buildup has caused at least two reactor buildings to explode.

“The priority would be the spent fuel pools because they are more exposed and it is more likely radioactivity could get out,” says David Lochbaum, director of the nuclear safety program at the Union of Concerned Scientists.

The fuel pools were designed they way they are because when the reactor complex was constructed decades ago engineers thought spent fuel would spend only a few weeks on-site before being shipped to a reprocessing plant elsewhere. But around the world the problems of finding safe sites, adequate transportation, and local populations willing to tolerate them have made large reprocessing facilities difficult to construct.

The good news is that at least some of the spent fuel rods from Fukushima had already been shipped elsewhere for safer dry cask storage.

Thus the vulnerable pools “weren’t filled to capacity,” says Lochbaum.

Japan nuclear crisis: A timeline of key events

The bad news is that enough fuel rods remain in the pools that, if exposed to air for a long enough period of time, it is theoretically possible that they could burn and melt into a pile of fissile rubble dense enough to restart a nuclear chain reaction.

Tokyo Electric Power said earlier this week that the possibility of such “recriticality” occurring in the pools is not zero. If it happened the pools would then in essence have turned into running mini-reactors, and begin emitting much more heat and dangerous radiation.

More boron is needed

Pouring water laced with boron into a pool would help stop such a reaction, as boron absorbs neutrons which are emitted during a nuclear reaction. Japan on Thursday announced plans to import 150 tons of boron from South Korea and France to replenish its stocks.

However, it is possible that water has leaked from the pools via cracks instead of boiled off or evaporated due to heat. If that is the case some of the heroic efforts by Japanese workers to spray water into the damaged containment buildings could be in vain.

Burying the spent fuel pools with sand and earth could prevent them from releasing any further radiation. But the act of shoveling stuff on top of the rods could break them up and force them together into a denser mass more prone to recriticality.

“You don’t want to solve one problem and cause another,” says David Lochbaum.