Cyber security in 2013: How vulnerable to attack is US now?

Loading...

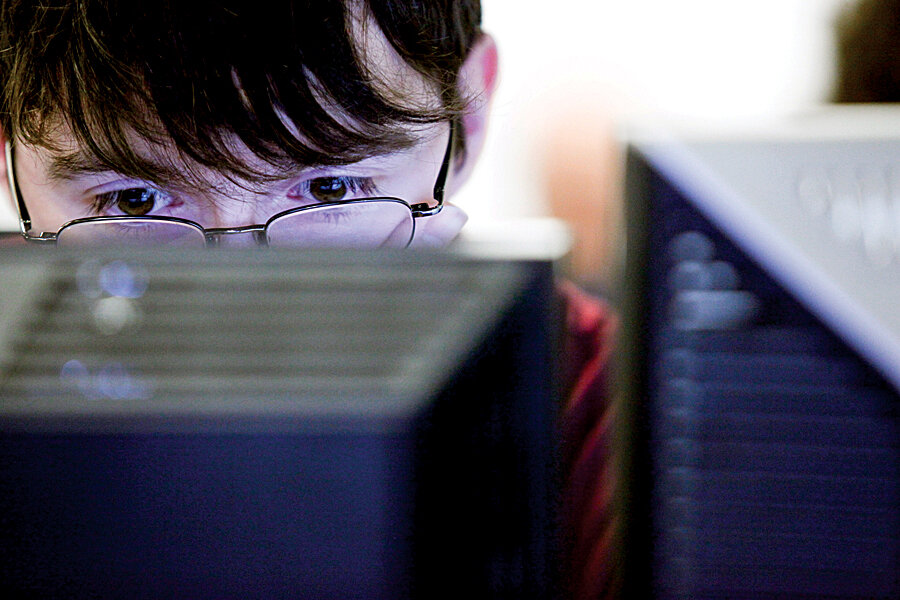

The phalanx of cyberthreats aimed squarely at Americans' livelihood became startlingly clear in 2012 – and appears poised to proliferate in 2013 and beyond as government officials, corporate leaders, security experts, and ordinary citizens scramble to devise protections from attackers in cyberspace.

Some Americans came screen to screen with such threats via their smart phones, discovering malicious software (malware) designed to steal their credit-card numbers, account passwords, and even the answers to their secret security questions. Others were temporarily blocked from accessing their bank accounts online, as US bank websites came under major attack at least twice in 2012 by a hacker group with possible ties to Iran. Some citizens learned that their home PCs had become infected by "ransomware," which locks up a computer's operating system until the bad guys get paid – and often even afterward.

But personal inconvenience is only the beginning. Homeland security is also at stake. The US government in 2012 learned that companies operating natural gas pipelines were under cyberattack, citing evidence that cyberspies, possibly linked to China, were infiltrating the companies' business networks. Those networks, in turn, are linked to industrial systems that control valves, switches, and factory processes. Utilities that operate the nation's electric grid are known to have been another target, as are US tech companies. Crucial government agencies, such as the Pentagon and the Federal Trade Commission, are also targets.

It all adds up to growing evidence – recognized to varying degrees by the US public, politicians, and businesses – that cybersecurity is the next frontier of national security, perhaps second only to safeguarding the nation against weapons of mass destruction.

"The cyberthreat facing the nation has finally been brought to public attention," says James Lewis, a cybersecurity expert with the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), a Washington national-security think tank. "Everyone knows it's a problem. It has moved out of the geek world, and that's a good thing. But it's led to more confusion than clarity. So now we're developing the skills to talk about it – and it's taking longer than I thought it would."

The awakening to cyberthreats has been gradual. In 2010, news of the world's first cyberweapon – the Stuxnet computer worm that attacked part of Iran's nuclear fuel program – burst upon the scene, raising concern about broad replication. Then came an increasing onslaught from hacktivist groups, which often stole and released private data. Between December 2010 and June 2011, for example, members of Anonymous were responsible for cyberattacks against the websites of Visa, MasterCard, and PayPal, as part of a tit for tat over the controversial WikiLeaks website.

Last year came the bald warning from Defense Secretary Leon Panetta of the possibility of a "cyber Pearl Harbor" – perhaps perpetrated by an enemy nation, extremist hacktivist groups, or cyber-savvy terrorists – that could be destructive enough to "paralyze the nation."

The threats originate from any number of sources: the lone hacker in the basement, networks of activists bent on cyber-monkey-wrenching for a cause, criminal gangs looking to steal proprietary data or money, and operatives working for nation-states whose intent is to steal, spy, or harm.

But at the Pentagon, attention these days is focused on the advancing cyberwar capabilities of China, Russia, and, especially, Iran. Iranian-backed cyberattackers, who in September targeted nine US banks with distributed denial-of-service attacks that temporarily shut down their websites, were testing America's reaction, Dr. Lewis says. The same kind of attack took place in December.

All the multiple attackers with various motives – and multiple targets – make defending against cyberattacks a challenge. Government agencies, the Pentagon, and defense contractors seem to have gotten serious and have greatly beefed up security. Companies' spending data also indicate an apparently growing awareness of the threat, with cybersecurity expenditures increasing.

But that's hardly enough, cyber experts such as Lewis say. Critical infrastructure needs to have its cybersecurity tested to ensure it's adequate, he and others say.

"Like anything else in America, there's a large, noisy debate driven by business interests and hucksterism – people shouting about cyberattacks," Lewis says. "But the situation is clearly serious. Our vulnerabilities are great. I recall our first CSIS meeting on cybersecurity in 2001. At that time, we agreed that if nothing significant was done to change things in a decade, we'd be in real trouble. Well, here we are."

What more to do?

Warnings such as the "Pearl Harbor" one from Mr. Panetta in October have stirred debate over further measures the United States should take to protect itself.

Congress recently grappled with legislation that would have allowed the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) to do cybersecurity testing on computer networks of companies that operate natural gas pipelines and other vital assets – and would have granted those companies protection from financial liability in the event of a cyberattack on their facilities. But lawmakers did not approve it, mainly on grounds that the business community objected to the expected high cost of the new mandates and regulations, as well as the exposure of proprietary information to government. In response, President Obama is expected to issue an executive order soon, though it won't give the federal government as much authority to conduct cyberdefense testing as the legislation would have.

Not everyone agrees on what defensive actions to take. Some see Panetta's words as hyperbole aimed mostly at preserving the defense budget. Others warn of a US policy "overreaction" in which Internet freedoms are stifled by Big Brother-style digital filters.

"As ominous as the dark side of cyberspace may be, our collective reactions to it are just as ominous – and can easily become the darkest driving force of them all should we over-react," writes Ron Deibert, a University of Toronto cyber researcher, in a recent paper titled "The Growing Dark Side of Cyberspace (... and What To Do About It)."

Still others doubt that America's cyberadversaries are as capable as they are made out to be. In Foreign Policy magazine in an article headlined "Panetta's Wrong About a Cyber 'Pearl Harbor,' " John Arquilla argues that the Defense secretary has employed the "wrong metaphor."

"There is no 'Battleship Row' in cyberspace," writes the professor of defense analysis at the Naval Postgraduate School in Monterey, Calif. "Pearl Harbor was a true 'single point of failure.' Nothing like this exists in cyberspace."

Scope of the damage

There's little question, though, that cyberthreats are already doing harm to the US economy – and may do even more.

"At a corporate level, attacks of this kind have the potential to create liabilities and losses large enough to bankrupt most companies," according to the US Cyber Consequences Unit, a think tank advising government and industry. "At a national level, attacks of this kind, directed at critical infrastructure industries, have the potential to cause hundreds of billions of dollars' worth of damage and to cause thousands of deaths."

Evidence of the damage includes the following:

• Cyberespionage that's intended to scoop up industrial secrets alone costs US companies as much as $400 billion annually, some researchers estimate. Much of that comes over the long term, as stolen proprietary data give firms in other nations, such as China, a leg up by slashing research-and-development costs.

• The volume of malicious software targeting US computers and networks has more than tripled since 2009, according to a 2011 report by the director of national intelligence. Reports in 2012 corroborate that upward trend.

• Ransomware netted cybercriminals $5 million last year, by some estimates. Smart-phone and other mobile cybervulnerabilities nearly doubled from 2010 to 2011, according to the cybersecurity firm Symantec.

• The Pentagon continues to report more than 3 million cyberattacks of various kinds each year on its 15,000 computer networks.

Defense contractors such as Lockheed Martin are key targets, too. At a November news conference, Chandra McMahon, Lockheed vice president and chief information security officer, revealed that 20 percent of all threats aimed at the company's networks were sophisticated, targeted attacks by a nation or a group trying to steal data or harm operations. "The number of campaigns has increased dramatically over the last several years," Ms. McMahon said.

Perhaps topping the list of concerns, though, is the accelerating pace of cyberattacks on the computerized industrial control systems that run the power grid, chemical plants, and other critical infrastructure.

"We know that [nation-state cyberspies] can break into even very security-conscious networks quite regularly if not quite easily," says Stewart Baker, a former DHS and National Security Agency (NSA) cyber expert now in legal practice at Steptoe & Johnson. "Once there, they can either steal information or cause damage."

In 2009, US companies that own critical equipment reported nine such incidents to the Industrial Control Systems Cyber Emergency Response Team, an arm of the DHS. In 2011, they reported 198.

"The threats to systems supporting critical infrastructures are evolving and growing," the Government Accountability Office concluded in a July report on the US power grid's exposure to cyberattacks.

The potential impact of such attacks, the report continues, "has been illustrated by a number of recently reported incidents and can include fraudulent activities, damage to electricity control systems, power outages, and failures in safety equipment."

Some experts say the rise in such incidents may be exaggerated. "What's happening is that our ability to identify attacks is improving, not necessarily that numbers or strength [of the attacks] is getting worse," says Robert Huber, a principal at Critical Intelligence, a cybersecurity firm in Idaho Falls, Idaho, that specializes in protecting critical infrastructure.

An awakening

A seminal speech on cyberthreats by Mr. Obama in May 2009 marked the onset of heightened public awareness of the problem. Cybersecurity would for the first time become an administration priority, he said, with a White House cyber czar and a "new comprehensive approach to securing America's digital infrastructure."

"Cyberspace is real, and so are the risks that come with it," Obama said. "It's the great irony of our Information Age – the very technologies that empower us to create and to build also empower those who would disrupt and destroy."

In particular, cybersecurity experts inside major corporations are becoming increasingly concerned. Corporate chief information security officers reported a 50 percent jump in the "measure of perceived risk" since March 2011, according to a cybersecurity index cocreated by Daniel Geer, chief information security officer of In-Q-Tel, the venture capital arm of the Central Intelligence Agency. In November, the index continued its upward march, rising 1.8 percent over the previous month.

Awareness is building among the public, too. Two-thirds of respondents to a national survey by the University of Oklahoma in February 2012 rated the threat of cyberwar at 6.5 on a scale where zero is "no threat" and 10 is "extreme threat." But only 1 in 3 rated themselves as having above-average knowledge about the cyberwar threat.

"These response patterns suggest a public that is aware of the emerging issue of cyber war, does not feel well informed about it, but perceives it to pose a substantial threat," the researchers reported.

Wariness and circumspection about cyberthreats are good first steps, cyber experts say, because they are the precursor to action. They say laws that require owners of critical infrastructure to meet cybersecurity performance standards are the next logical step.

"It's clear we have enemies who'd love to [attack US critical infrastructure], especially if they could escape blame for doing so," says Mr. Baker, the former NSA cyber expert. "It may not happen soon. But we would be crazy to assume it will never happen."