Will a makeover improve the GED's value?

| Boston

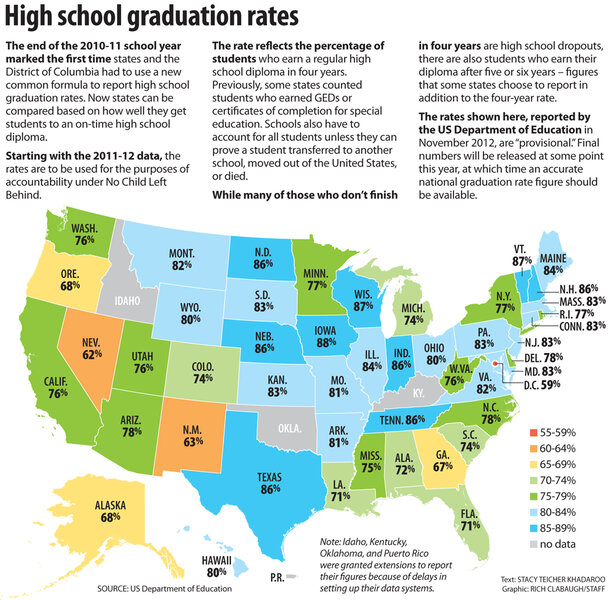

An estimated 40 million US adults have not finished high school.

Every year, about 800,000 people take GED tests, and more than 400,000 succeed in earning the GED, a high school equivalency credential that's recognized in all 50 states.

But "the value of the GED is in question," says Jonathan Zaff, director of the Center for Promise, a research center based at Tufts University in Medford, Mass., and sponsored by America's Promise Alliance, a youth-advocacy coalition.

Some research finds that, economically, GED-holders tend to fare about as well as high school dropouts with no GED, Mr. Zaff says. That may be one reason the GED is undergoing a transformation – the biggest in its 70-year history. And it's stirring up controversy along the way.

The new test is designed "to embrace the college- and career-readiness standards" that states have been adopting, says Randy Trask, president of GED Testing Service in Washington.

The test will roll out in January 2014, so people preparing for the current GED have just under a year to finish up.

Test-takers will be required to show how they can use what they've learned to solve real-world problems, Mr. Trask says. Also, the test will be computerized, he says, a delivery system that some states have already begun to adopt.

The plans have raised concerns about educational access – especially since the new tests, as well as a new cost structure, coincide with a private company becoming involved in the GED tests for the first time.

The GED has traditionally been run by the American Council on Education, a nonprofit higher-education association in Washington. In March 2011 it partnered with Pearson, a for-profit provider of educational materials and services, to form the new GED Testing Service.

That "raised some red flags for us," says Wade Henderson, president and chief executive officer of The Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights, a coalition based in Washington.

The GED "is a gatekeeper to opportunity for our most poor and most vulnerable citizens," he says. "It needs to be strengthened and aligned to current core standards ... but it won't succeed if the costs are too high."

Costs for taking the test ranges from nothing to as much as $200 or more, depending on where test-takers live. The cost of the new computerized test will be $120; but as before, how much of that is passed on to test-takers will vary. Moreover, it's unclear whether the price will go up after 2014.

Out of 26 states that set prices, 25 charge less than $120, according to the National Council of State Directors of Adult Education.

Mr. Henderson also wonders if all testing centers can make the transition from pencil and paper to computers in time and prepare non-computer-savvy students.

The new system might save states money. Under the old cost model, they leased the test and had to pay for oversight and grading themselves, Trask says.

The new price reflects a centralization of costs. Discussions should be under way at the federal, state, and local levels, he says, about how to ensure that those most in need can take GED tests.

The next step, Trask says, is connecting the GED with more pathways into college or vocational training. For instance, he's hoping to develop bridge courses between the GED and certifications in the information technology industry.