Amelia Earhart mystery: Sonar image a new clue to missing plane?

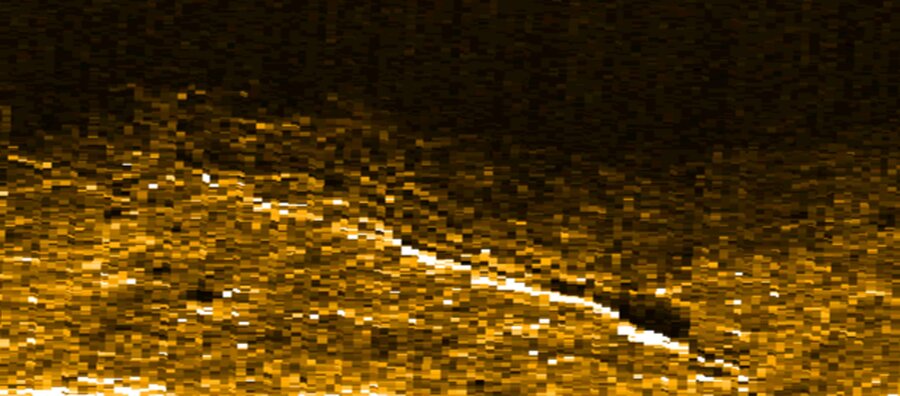

The blocky sonar image of the Pacific Ocean floor isn’t much to look at, just a mosaic of yellow and black pixels streaked with white.

But this fuzzy image could hold the key to solving one of the most enduring mysteries of modern history: What happened to Amelia Earhart?

According to a nonprofit organization called The International Group for Historic Aircraft Recovery (TIGHAR), which has been hunting for the aviator's downed plane for at least two decades, the image shows an “anomaly” on the sea floor near the tiny South Pacific island of Nikumaroro. And there’s reason to believe, the group says, that that anomaly could be the wreckage of Earhart’s iconic Lockheed Electra, which lost contact with the US Coast Guard on a slightly overcast July morning in 1937, never to be heard from again.

“It’s exciting. It’s frustrating. It’s maddening,” the organization wrote of the image, which it found while combing through data collected on a trip to Nikumaroro last summer – the group’s ninth since it began its hunt for the Electra in 1989.

“Listen, we’re realistic: This could be coral, this could be a sunken fishing boat, but it looks promising,” says Ric Gillespie, TIGHAR’s executive director. “It’s a great clue.”

Now Mr. Gillespie is asking supporters for $3 million to chart a new expedition to the island to take peek at the “anomaly” up close.

While that’s not exactly small change, he has easily raised similar sums in the past. All in all, he says, his group has spent about $6 million on Earhart searches in the past 25 years, the majority of it raised from individual donors who want to be a part of solving aviation’s greatest whodunit.

Earhart was at the apex of a glamorous flying career when she and navigator Fred Noonan decided to attempt a circumnavigation of the globe in the summer of 1937. They were 18 hours into their flight when a Coast Guard ship stationed near the Pacific island of Howland received a message asking for help guiding the plane to shore.

That was the last the duo were ever heard from. Despite an exhaustive search, no traces of their plane or their bodies were ever found.

As the search ground on, a new brand of Earhart fixation began, says Susan Ware, author of "Still Missing: Amelia Earhart and the Search for Modern Feminism."

“There are really two Amelias, the Amelia of history and the Amelia locked in this mystery of the missing plane,” she says. “Hers is a fascinating story, but it’s one without an ending, and people can’t seem to get over that.”

That’s where individuals like Gillespie come in. Over the years, other researchers and scholars gradually gave up hope of finding the downed plane, figuring it was likely resting on the ocean floor thousands of feet below the shark-infested waters near Howland.

But Gillespie, a former airline crash investigator, had another theory.

What if, after Earhart lost contact with the Coast Guard, her plane staggered onward for a while longer? After about 2-1/2 hours traveling in the direction she last radioed to the ship, she would have reached Nikumaroro, a tiny, donut-shaped island in what is now the nation of Kiribati.

Earhart may have crash-landed there, Gillespie says, and the wreckage of her plane would have eventually washed out to sea.

There’s a strange collection of circumstantial evidence to support this theory. Three years after the disappearance, for instance, a colonial administrator found a human skeleton, the scraps of some shoes, and a liquor bottle on the island. The skeleton, which has since gone missing, is thought to have been of a woman of Northern European origin, about 5 feet, 7 inches in height. (Earhart was 5-foot-8.)

Gillespie and his team say that over the years they’ve found other archeological evidence on the island – including what they say may be a bottle of Earhart’s antifreckle cream – to support the notion that the two were there, alive, for an undetermined length of time.

TIGHAR, which has located several other wrecks, hopes to launch a two-ship expedition to Nikumaroro to investigate the possible plane wreckage. That will be bankrolled by its 1,100 members and assorted members of a public that seems unwilling to give up on the possibility, however distant, that this mystery may one day be laid to rest.

“She’s become a legend, regardless of who she really was or what she was like,” he says. “We want her found.”