New index reveals sobering picture of how much African-American children lag

Loading...

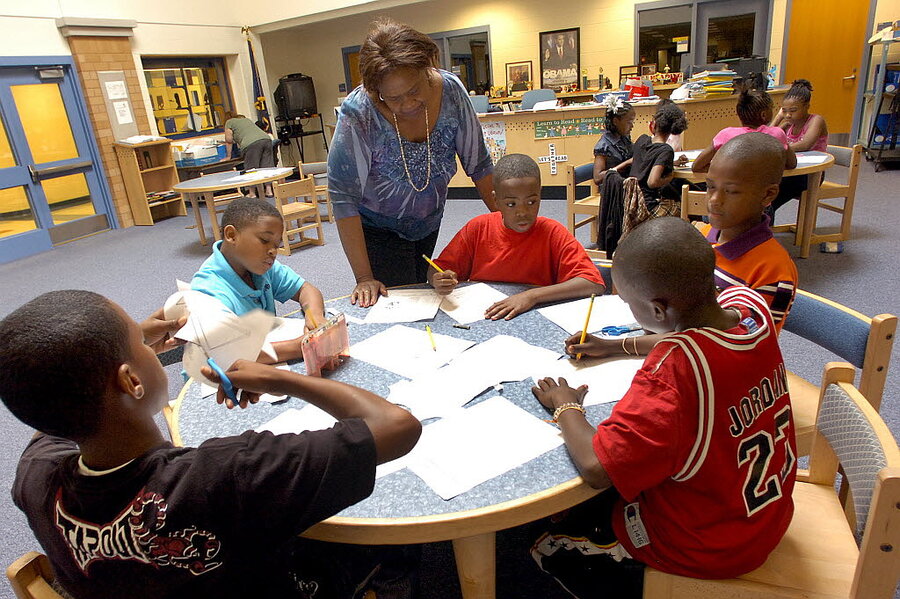

Children of color – and African-American children in particular – face enormous opportunity barriers compared with their white and Asian counterparts, according to a new report, which characterized the wide gaps as a national crisis.

The "Race for Results" report from the Annie E. Casey Foundation, part of its annual “Kids Count” publications, broke down data on education, family resources, and neighborhood by race and by state, looking at key indicators that predict how likely a child is to succeed in life. It found immense differences in the barriers encountered by children of different races.

The 12 indicators, which the foundation selected for their bearing on “the likelihood of a young person becoming middle class by middle age,” include enrollment rates in preschool, fourth-grade proficiency in reading, on-time high school graduation, delaying pregnancy to adulthood, normal birth weight, whether children live in two-parent families or with at least one person who has a high school diploma, and the poverty level of their family and their neighborhood.

Researchers developed methodology to standardize and compile scores for the 12 indicators and translate them to an overall score on a scale ranging from 0 to 1,000.

That composite index, in which African-American children fared the worst, revealed massive gaps. Nationally, Asian and Pacific Islander children scored the best, with an index score of 776, followed closely by white children at 704. Scoring significantly different were Latinos (404), American Indians (387), and African-Americans (345).

“While it’s clear no one racial group has all kids meeting all milestones at the national level ... we see big differences by race,” said Nonet Sykes, a program officer at the Casey Foundation and a contributor to the report, in a presentation Tuesday highlighting the report’s findings.

Compiling the indicators into one score helped to highlight just how serious the opportunity gap is, says Laura Speer, the Casey Foundation's associate director for policy reform and advocacy and an author of the study. When you see that 87 percent of African-American babies are born at a normal birth weight, compared with a national average of 92 percent, that's disturbing but doesn't seem like a crisis on its own, she says. "When you look at this data compiled in the way we did it, it really reinforces that these are kids that are facing multiple barriers. It's not just about their math skills or whether they have a job as a young adult: It’s a series of barriers they have to overcome."

The foundation chose to highlight gaps based on race in part because of America’s growing diversity. According to the report, by 2018 a majority of America’s children will be children of color; by 2030, a majority of the US labor force will be people of color.

"As our country becomes more diverse, our future success hinges more and more on children of color," Ms. Speer says. "This is a time when we really can’t leave them behind. We can’t leave their talent on the table; we don’t have that luxury going forward."

The low index scores for African-American children, in particular, “should be considered a national crisis,” the report said.

Just 17 percent of African-American students were proficient in reading by fourth grade – a crucial indicator of future success in school and work – and just 14 percent were proficient in math in eighth grade. African-American children were also by far the least likely to live in two-parent families (37 percent) and the most likely to live in a family or neighborhood with poverty.

States in the South and Midwest had the worst scores for African-American children, with Mississippi and Wisconsin scoring just 243 and 238 on the 1,000-point scale. The poor scores for Wisconsin – a state that has always fared well in overall "Kids Count" studies – as well as Michigan highlight the need to zero in on Rust Belt cities like Milwaukee and Detroit where African-American children are struggling, Speer says.

American Indian children also encounter considerable challenges, according to the report, though their scores vary widely by region and by tribe.

Nearly half of Choctaw children live in families with incomes at or above 200 percent of the poverty level, for instance, compared with just 20 percent of Apache children. By state, index scores for American Indian children ranged from 185 for South Dakota – the lowest of any group in the study – to 631 for Texas.

Latinos were the least likely to have children aged 3 to 5 enrolled in preschool, nursery school, or kindergarten, and just 19 percent of Hispanics between 25 and 29 have completed an associate's degree or higher, compared with a national average of 39 percent. Sixty-three percent of Latino children live in a household that includes someone with a high school diploma, compared with 93 percent of white children.

There was less geographic variation – and higher overall scores – for white children, but still some considerable differences by state. White children in the Northeast fared the best, with index scores of 827 for both Massachusetts and New Jersey, while those in West Virginia came in at 521.

“We’re learning that too many of our children are consigned to the sidelines as if they’re not worth investing in,” said Patrick McCarthy, CEO of the Casey Foundation, in the Tuesday presentation.

The report highlighted the consequences of not addressing the gaps in opportunity, noting a McKinsey & Co. study that concluded if the United States had closed the achievement gap by 1998, and African-American and Latino students had caught up with white students, America’s GDP in 2008 would have been $525 billion higher.

“Our nation cannot afford to leave this talent behind in hopes that these problems will remedy themselves,” the "Race for Results" report concluded, saying that the statistics should be seen as “a call to action.”

Among other things, the report advocates increased use of disaggregated data to inform decisionmaking, targeting investments to programs that yield the greatest impact for children of color, and the implementation of more evidence-based programs focused on improving outcomes for children of color.

It also highlights some successful programs when communities do choose to zero in on a specific problem, like an initiative in Ventura County, Calif., to combat big racial disparities in the juvenile justice system. In particular, Latino and African-American youths were significantly overrepresented in the population admitted to secure facilities for warrants. After extensive data collection, groups tackling the problem identified two key areas for intervention – making sure youths appeared in court and reducing detention from bench warrants – and were able to make big progress on the disparities.

"It’s about making small changes" and often addressing one issue at a time, says Speer. "There are places like that – access to early-childhood education, for instance – that can really make a difference and can close some of these racial gaps on these key measures."