Iraq war judged a mistake by today's White House hopefuls

Loading...

| Washington

A dozen years later, American politics has reached a rough consensus about the Iraq War: It was a mistake.

Politicians hoping to be president rarely run ahead of public opinion. So it's a revealing moment when the major contenders for president in both parties find it best to say that 4,491 Americans and countless Iraqis lost their lives in a war that shouldn't have been waged.

Many people have been saying that for years, of course. Polls show most of the public have judged the war a failure by now. Over time, more and more GOP politicians have allowed that the absence of weapons of mass destruction in Iraq undermined Republican President George W. Bush's rationale for the 2003 invasion.

It hasn't been an easy evolution for those such as Democratic presidential candidate Hillary Rodham Clinton, who voted for the war in 2002 while serving in Congress. That vote, and her refusal to fully disavow it, cost her during her 2008 primary loss to Barack Obama, who wasn't in the Senate in 2002 but had opposed the war.

In her memoir last year, Clinton wrote that she had voted based on the information available at the time, but "I got it wrong. Plain and simple."

What might seem a hard truth for a nation to acknowledge has become the safest thing for an American politician to say — even Bush's brother.

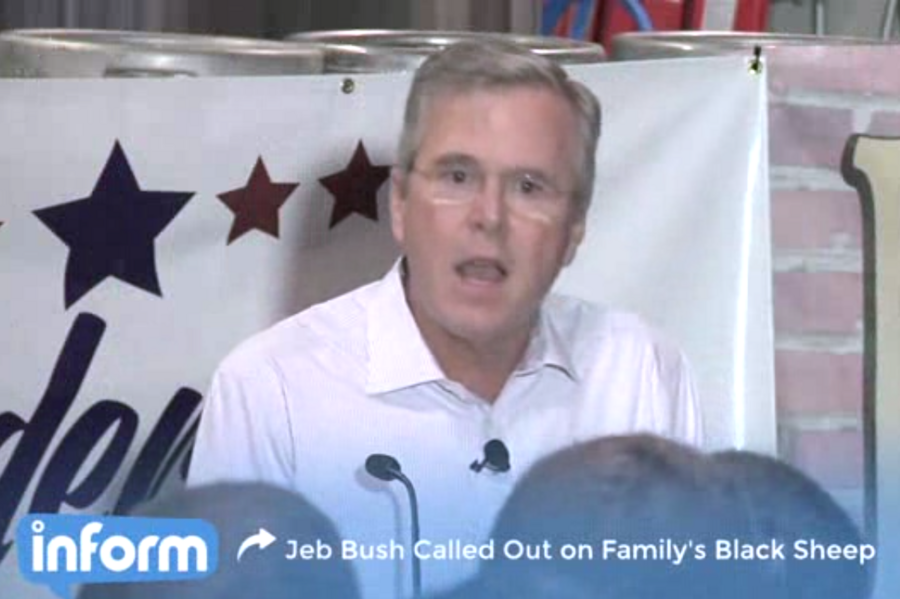

The fact that Jeb Bush, a likely candidate for the Republican nomination in 2016, was pressured this past week into rejecting, in hindsight, his brother's war "is an indication that the received wisdom, that which we work from right now, is that this was a mistake," said Evan Cornog, a historian and dean of the Hofstra University school of communication.

Or, as Rick Santorum, another potential Republican candidate, put it: "Everybody accepts that now."

Santorum didn't always see the war that way. He voted for the invasion as a senator and continued to support if for years. Last week, he mocked Jeb Bush's reluctance to give what now seems the obvious answer when he was initially asked to reconsider the war in light of what's known today. "I don't know how that was a hard question," Santorum said.

It's an easier question for presidential hopefuls who aren't bound by family ties or their own congressional vote for the war, who have the luxury of judging it in hindsight, knowing full well the terrible price Americans paid and the continuing bloodshed in Iraq today.

Florida Sen. Marco Rubio and Texas Sen. Ted Cruz weren't in Congress in 2002 and so didn't have to make a real-time decision with imperfect knowledge. Neither was New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie or Ohio Gov. John Kasich, who served an earlier stint in Congress.

All these Republicans said last week that, in hindsight, they would not have invaded Iraq with what's now known about the faulty intelligence that wrongly indicated Saddam Hussein had stockpiled weapons of mass destruction.

Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker, in an interview Sunday on CBS' "Face the Nation," summed up that sentiment: "Knowing what we know now, I think it's safe for many of us, myself included, to say, we probably wouldn't have taken" that approach.

Those politicians didn't go as far, however, as war critics such as Kentucky Sen. Rand Paul, a declared Republican candidate who says it would have been a mistake even if Saddam were hiding such weapons. Paul says Saddam was serving as a counterbalance to Iran and removing him from power led to much of the turmoil now rocking the Middle East.

Former President George W. Bush and his vice president, Dick Cheney, still maintain that ousting a brutal and unpredictable dictator made the world safer.

In his 2010 memoir, "Decision Points," Bush said he got a "sickening feeling" every time he thought about the failure to find weapons of mass destruction and he knew that would "transform public perception of the war."

But he stands by his decision.

The war remains a painful topic that politicians must approach with some care.

Jeb Bush, explaining his reluctance to clarify his position on the war's start, said "going back in time and talking about hypotheticals," the would-haves and the should-haves, does a disservice to the families of soldiers who gave their lives.

Cornog, the historian, said even if a majority of Americans have turned their backs on the war, many never will.

"I think if I had lost a loved one in that war I would be unwilling to say it was a futile effort or destructive of America's security," he said. "How we interpret it depends on how we are invested in the question at hand."

When he finished withdrawing U.S. troops in December 2011, Obama predicted a stable, self-reliant Iraqi government would take hold. Instead, turmoil and terrorism overtook Iraq and American leaders and would-be presidents are struggling with what to do next. The U.S. now has 3,040 troops in Iraq as trainers and advisers and to provide security for American personnel and equipment.

For the most part, the public and the military — like the politicians — are focused less on decisions of the past than on the events of today and how to stop the Islamic State militants who have overrun a swath of Iraq and inspired terrorist attacks in the West.

"The greater amount of angst in the military is from seeing the manifest positive results of the surge in 2007 and 2008 go to waste by misguided policies in the aftermath," said retired U.S. Army Col. Peter Monsoor, a top assistant to Gen. David Petraeus in Baghdad during that increase of U.S. troops in Iraq.

"Those mistakes were huge and compounded the original error of going into Iraq in the first place," said Monsoor, now a professor of military history at Ohio State University. "There's plenty of blame to go around. What we need is not so much blame as to figure out what happened and use that knowledge to make better decisions going forward."