‘It can’t happen here.’ Coronavirus hits rural America.

| Austin, Texas, and Tybee Island, Ga.

Rep. Vikki Goodwin’s district in Texas took swift action to protect residents from the novel coronavirus in early March. Austin canceled the popular SXSW festival for the first time in more than three decades, losing an estimated $350 million in revenue.

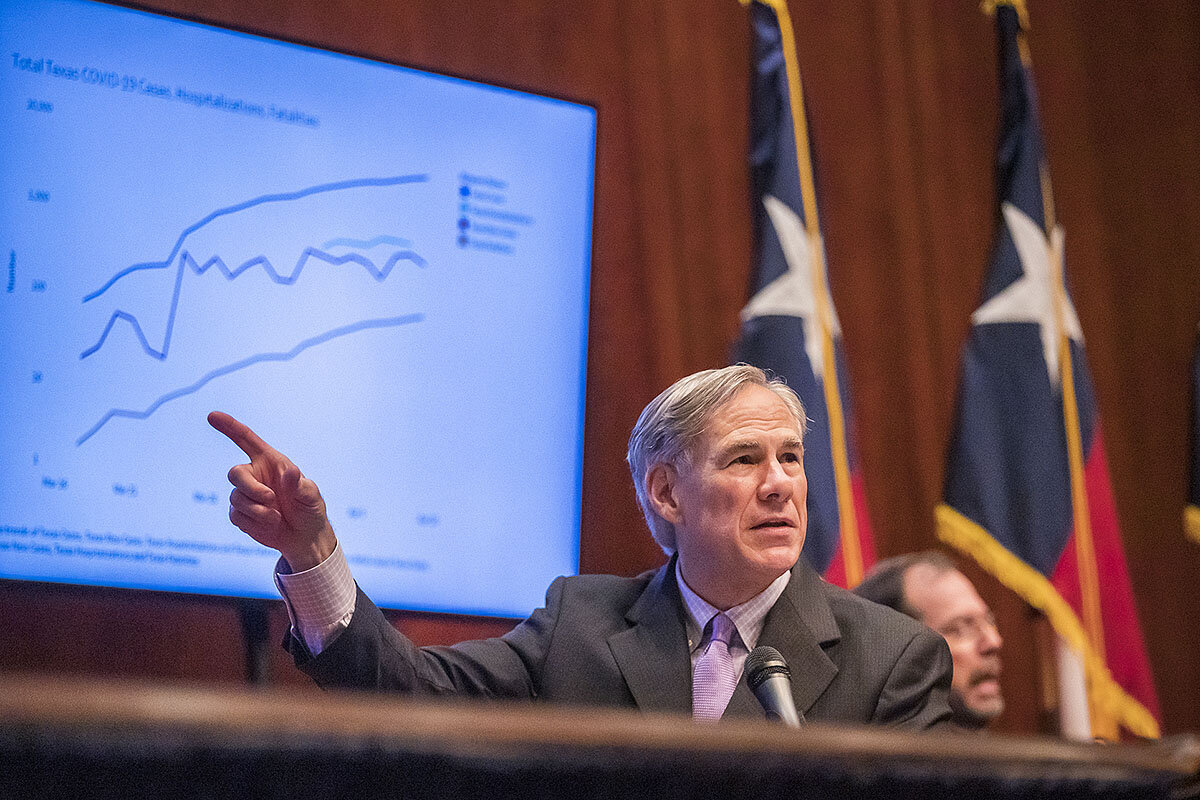

But last week, 30 miles out in her district, which stretches into the sparsely populated Hill Country, the town of Lago Vista's golf course was still open – a week after Republican Gov. Greg Abbott issued a statewide stay-at-home order.

In more suburban and rural stretches of Texas, there seems to be a sense that the virus is a distant, perhaps overblown, crisis.

Why We Wrote This

Where Americans live can have a lot to do with how they see the coronavirus crisis. In rural areas, there was initially a false sense of security. But that may be changing.

Editor’s note: As a public service, all our coronavirus coverage is free. No paywall.

“That’s a concern to me,” says state Representative Goodwin, a Democrat. “In rural areas the feeling is it hasn’t gotten there yet and it won’t spread. There’s maybe a false sense of security.”

The U.S., as has been widely reported, has adopted a state-by-state approach to battling the novel coronavirus. But there’s also a divide between steps taken in America’s large cities, where the disease hit first, and its rural counties, where people might not be able to even see their nearest neighbor and social distancing has long been a way of life. The idea that “it can’t happen here” also plays on cultural suspicions that date back to Aesop’s Fables, where the country mouse tells the city mouse she prefers her plain food and simple life in the country with the peace and security that go with it.

Now, as COVID-19 sweeps into small-town America – with two-thirds of rural counties reporting at least one confirmed case as of last week – a new pandemic geography is emerging. In a recent poll, 74% of Democrats support restrictive policies to protect people, including some infringements on civil liberties, as did 71% of Republicans.

“The initial take among a lot of elected officials and Southerners in general, especially in rural areas, was ... ‘This is their problem. We don’t see it,’” says Cal Jillson, a political scientist at Southern Methodist University in Dallas. “When you put the importance of church with the small government ethic and where people don’t want to be told what to do, it’s true, you can do the wrong thing for a good and understandable reason and still pay a very heavy price.”

In rural America, that’s playing out from pews to boat ramps.

In St. Augustine, Florida, some 10,000 people have signed Eric Hires’ petition to reopen the beaches of St. Johns County, despite the state’s 20,000 confirmed cases.

“People have called me selfish, but this has become much bigger than me,” says Mr. Hires, a surfer in his 30s, in a phone interview. He points out the golf course was allowed to stay open, and says he just wants early and late-morning hours with no congregating. “I’m more libertarian. I don’t like the government infringing on rights or freedoms. But there is also an element of personal freedom. If you live near the beach and the ocean is your sanctuary, you should be able to go there.”

Where social distancing is built in

Some 9 in 10 Texans live in or near a big city, but the state boasts vast stretches of ranchland, scrub, and desert. Until early April, Governor Abbott preferred to let cities and counties decide for themselves the wisest course of action.

As more cases were reported, Lyle Larson, a Republican state representative from San Antonio, had been calling for weeks for a statewide order. He understands the various interests the governor had to balance, however, including politics and broader health care realities, including that 26 rural hospitals have closed across the state since 2010.

“Some people don’t like the government making blanket declarations on what they can and can’t do, and there are others who want a total shutdown,” says Representative Larson. People in rural areas have social distancing “already built into their lifestyle,” he adds, but when the statewide order went into effect, “people took that seriously.”

A handful of states with large rural populations have yet to order statewide lockdowns, trying to balance local interests against what former FEMA director Craig Fugate calls a “slow-rolling disaster.”

“What is happening is that there is much less coordinated federal control in this emergency than in past ones, so you do see an absolute flowering of federalism driven by ... geography, demography, and ideological makeup,” says Mr. Jillson. “That means if you are in the South or Mountain West and you have a diverse state geographically – a few major cities and large open stretches between them – you have been conflicted as to how to proceed.”

Noting a regional difference, “we’ve been pretty aggressive as a geography and I think that’s important,” Michigan Gov. Gretchen Whitmer, a Democrat, said on CNN. Governor Whitmer issued a stay-at-home order in March, one of the first governors to do so, but Michigan remains one of the hardest-hit states, with about 25,000 cases.

In contrast, South Dakota Gov. Kristi Noem, a Republican, told a press conference in early April that “the people themselves are primarily responsible for their safety.” And, she added, “South Dakota is not New York City.” Over the weekend, one of the largest pork processors in the U.S., Smithfield, announced it was shutting down its Sioux Falls plant indefinitely after 293 workers tested positive.

People talk about infringements on constitutional rights, but “what I think people forget about is their constitutional responsibilities: You live in this country and you have a duty that includes not endangering others,” says Polly Price, a professor of law and global health at Emory University in Atlanta. “This kind of effort relies on citizen participation.”

“Scratching my head”

On Tybee Island, the stakes have risen dramatically. On March 20, after spring break crowds flocked along Tybrisa Street, the city barricaded the beach.

But in early April, as part of a statewide lockdown order, Republican Gov. Brian Kemp reopened the beaches to allow Georgians to access their common outdoor property. His chief of staff even urged, “Go to the beach!”

As a precaution, Governor Kemp sent dozens of state troopers and game wardens to patrol to make sure social distancing protocols were observed.

Ken and Jessica Branch drove down from North Carolina, where beach communities have closed off access to outsiders.

“As long as we abide by the rules, I think we’ll be OK. We needed a break. We needed this,” says Ms. Branch.

Tybee local Dan Lockwood, on the other hand, watched beachgoers violate six-foot distancing orders as they passed each other on narrow dune overwalks. “Governor Kemp is basically saying, ‘Stay at home, but don’t take it seriously,’” says Mr. Lockwood.

Like many Republicans along the conservative Georgia coast, state Rep. Jeff Jones, a carwash operator, has struggled to come to terms with the governor’s decision.

On one hand, he says, “I think media reporting of the CV-19 outbreak is overblown.”

Yet Representative Jones disagrees with Mr. Kemp’s decision to reopen the beaches, including those in his district at St. Simons Island.

“I am scratching my head,” he writes in an email. “Locally, we logically knew that if people travel away from their homes, the chances of spreading the highly contagious CV-19 increased exponentially. This has, no surprise, turned out to be correct.”

To Mr. Fugate, who served as Florida’s emergency director under former Republican Gov. Jeb Bush and as FEMA director under Democratic President Barack Obama, the case-by-case approach underscores larger failures of communication as the pandemic moves into arguably more vulnerable populations, given health and welfare disparities in the South.

“Until we have enough ability to do rapid testing and until everybody self-isolates, we are still on the front end of the pandemic,” says Mr. Fugate, who hails from a Southern tobacco farming family and vacations on Georgia’s Jekyll Island. “We’re seeing places like New York explode, we’re watching New Orleans explode, and then now Albany, Georgia, and these micro-areas that don’t have a lot of depth [in their health care systems]. We know what to do, yet we are reluctant or slow to embrace the only tools that we have. It’s a brutal math: Do people die or do businesses die?”

No cruise ships, but no lockdown

The fears of outsiders played out in Huntsville, Alabama, as the crisis began in late February.

A federal plan to house stricken cruise ship passengers on a decommissioned Army base fell apart amid a conspiracy theory-fueled pushback from residents and politicians. Seeing what he considers a lack of resolve in the federal response, Michael Barton, Calhoun County emergency management director, initiated the state’s first infectious disease task force.

Until two weeks ago, Alabama had not recorded a single death and Republican Gov. Kay Ivey had resisted a lockdown. “Y’all, we are not California,” she said. “We are not New York. We are not even Louisiana.”

But by last week, as the state recorded 1,400 cases – including 200 nurses – Governor Ivey switched course, ending a press conference with a prayer for Alabamans’ safety.

“Those numbers are increasing and that gets people’s attention,” says Mr. Barton, a former special deputy United States marshal. “Sure, we have some people saying it’s overblown. But the mantra we are following here is we are going to prepare for the worst and work for the best.”

On Tybee Island, the crowds never really arrived. While the beaches are technically open, the city fought to keep the majority of narrow dune crossovers closed to enforce distancing. And after the town of 3,000 people – which has at least six first responders in quarantine and two hospitalized city employees – became inundated with requests for short-term rentals, the governor reinstated the ban on rentals in an amended order Wednesday.

“This is the challenge with mixed messages in a crisis: Telling people what to do isn’t really always effective,” says Mr. Fugate. “What is effective is telling people the why and giving them the information to make a decision.”

Editor’s note: As a public service, all our coronavirus coverage is free. No paywall.