Enduring message of nonviolence reaches new audiences

Clarence B. Jones is preaching nonviolence.

At 93, this civil rights pioneer, who helped the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. write his “I Have a Dream” speech, is still combating hate. But these days, instead of leading protest meetings, Dr. Jones is reaching young audiences through new channels such as the Institute for Nonviolence and Social Justice and the Spill the Honey Foundation; with his recent memoir, Last of the Lions; and by starring last month in television’s most expensive real estate – a Super Bowl ad to combat antisemitism.

Why We Wrote This

In a nation focused on divisions, voices are rising for peace. One of these, civil rights activist and nonviolence advocate Clarence B. Jones, who helped write the famous “I Have a Dream’’ speech, is finding new audiences.

“Each day, something happens that makes me more convinced of the power and the goodness of the soul of America,’’ says Dr. Jones. “There are deep veins of decency and love and compassion. Yeah, I know all about the violence. I know about the 643 mass killings in this country. I see what’s going on at the border. I got all of that. But against all of that is the deep vein of decency that grounds America.’’

Today, he says, his commitment is as intellectual as it is emotional. “I know the power of nonviolence,’’ he says, “of Dr. King’s belief that, quoting him, there was no one whose soul is beyond redemption.’’

Clarence B. Jones is preaching nonviolence.

At 93, this civil rights pioneer, who helped the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. write his “I Have a Dream” speech, is still combating hate. But these days, instead of leading protest meetings, Mr. Jones is reaching young audiences through new channels such as the Institute for Nonviolence and Social Justice and the Spill the Honey Foundation; with his recent memoir, Last of the Lions; and by starring last month in television’s most expensive real estate – a Super Bowl ad to combat antisemitism.

The Monitor spoke with Dr. Jones about his work with Dr. King and the enduring relevance of nonviolent activity. This conversation has been edited for clarity and length.

Why We Wrote This

In a nation focused on divisions, voices are rising for peace. One of these, civil rights activist and nonviolence advocate Clarence B. Jones, who helped write the famous “I Have a Dream’’ speech, is finding new audiences.

There’s an online video of New England Patriots owner Robert Kraft telling you the Super Bowl ad with you in it was scheduled to run. You cried. Why was that so emotional for you?

It was emotional for me because I knew how timely the subject matter was for what’s going on in our country. And I didn’t anticipate that I would have an outlet of such national stature and reach to transmit a message that means so much to me.

Talk about today’s social justice movements and how they’re different from when you worked with Dr. King in the ’60s.

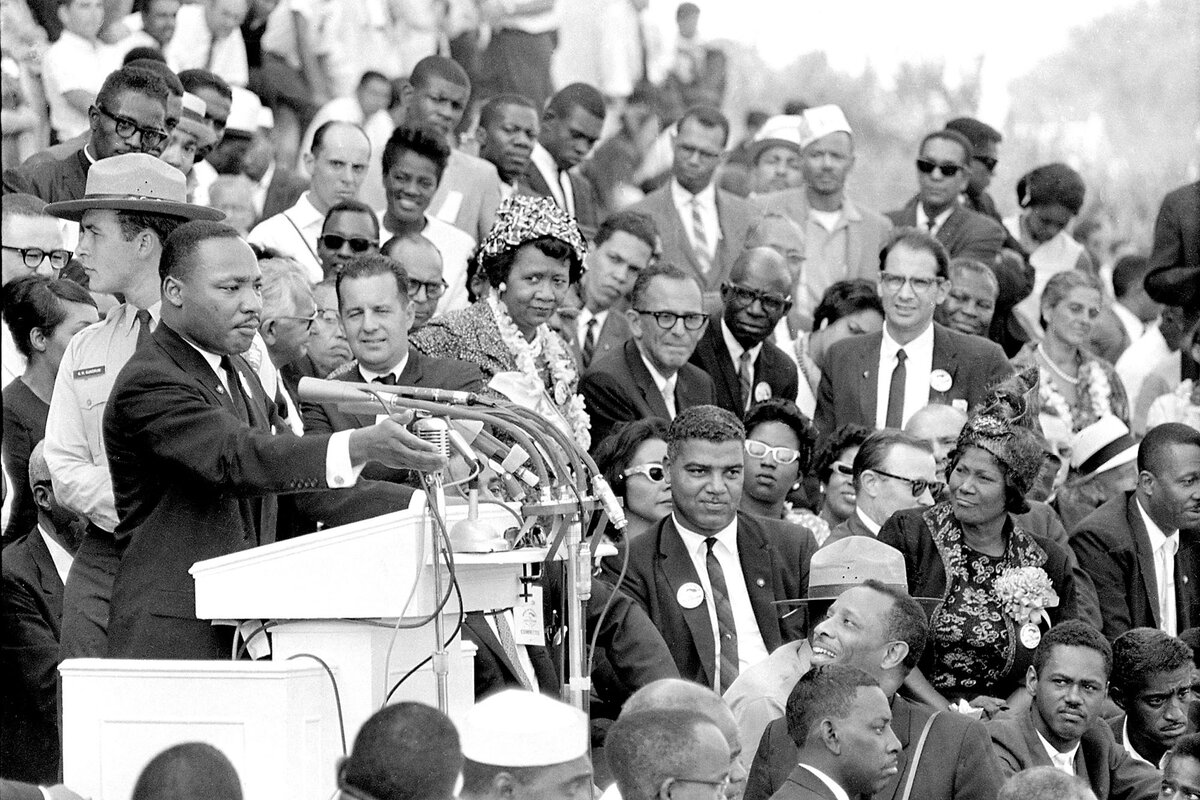

If we had had cellphones and iPads in 1963 when we were planning the [March on Washington], instead of having some 250,000 people, we’d have had 5 million people come to the Lincoln Memorial. That shows the power of technology.

I speak to you from the confidence of the power of our ideas. In the 1960s, the country was living in a contradiction. More and more people began to see this. And the reason they were able to see it is because they had the emergence of an extraordinary, powerful preacher who spoke in biblical moral terms that cut across generations and cut across religions and put it in simple terms.

Each day, something happens that makes me more convinced of the power and the goodness of the soul of America. There are deep veins of decency and love and compassion. Yeah, I know all about the violence. I know about the mass killings in this country. I see what’s going on at the border. I got all of that. But against all of that is the deep vein of decency that grounds America. And when you’re 93 years old, you have the luxury of looking back over a long period of time and comparing it to what you witnessed and experienced then and what you see today. Your glass can either be half empty or half full, and my glass is always half full.

Was it difficult to stay committed to nonviolence when you were working with Dr. King?

He was totally, deeply, irrevocably, morally, religiously, philosophically committed to nonviolence. For me, it was difficult. I was a pragmatist. All of that changed when I saw courage on his part. It just melted my intransigence away.

Today, my commitment is sheerly by the force of intellect. I know the power of nonviolence, of Dr. King’s belief that, quoting him, there was no one whose soul is beyond redemption.

What is the most important work you’re doing now?

Spill the Honey is a foundation dedicated to telling the story and commemorating the legacy of the work between the Black and Jewish communities that made the Civil Rights Movement possible. I’m on the board.

The historic alliance cannot be changed. Cannot be erased. We would not be the country we are today but for the coalition and cooperative alliance between the Black and Jewish community.

Do you have a set of guiding principles for a meaningful life?

I have seen and witnessed unspeakable violence. I have seen and witnessed acts of courage and generosity and love that are beyond rational description. I’ve experienced it. I’ve seen people break down and sob and be destroyed, and I’ve seen them put back together piece by piece and go on and make something of themselves.

You’re speaking to the power of love.

You’ve got it – the power of love. I have experienced anger at which I wanted to just take all the power of my being to kill and destroy. But I over[came it], thanks to Martin Luther King Jr. In the end, I know I am a compassionate, loving, caring person.

Is there anything we’ve left out that you’d like to leave with readers?

My parents were domestic household servants. My father had a fourth grade education and my mother had around a third grade education. From the age of 6 to 14, I spent most of my time raised by Irish Catholic nuns in the Order of the Blessed Sacrament. They used to hug me and other boys – ”colored” boys, as we were referred to, and some Native Americans. And they used to say, Master Jones, be a good boy. We love you. Jesus loves you. And you are beautiful. At the age of 14, when I got to public school, 70% white, 30% Negro, I still believed that. I thought I was beautiful. And thinking I was beautiful enabled me to have a sense of self, a sense of purpose, a sense of confidence. [I] graduated as valedictorian of my class.

I tell – particularly Black young boys and girls, when I have a chance to talk to them, some of whom have been incarcerated or they’re in juvenile detention – I say, before you go to bed at night look into the mirror and say three times: “I am somebody. I am beautiful. I am somebody. I am beautiful. I am somebody. I am beautiful.” Because if you do not believe in yourself, how can you expect somebody else to believe in you? If you don’t love yourself it’s asking a lot for somebody else to love you.